- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Floating in outer space’

- Article Subtitle: Two decades of Tampa politics

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In late August, it took only a few days for the Taliban to secure control of Kabul in the wake of the final withdrawal of Western troops from Afghanistan. The breakneck speed of the takeover was accompanied by images of mass terror, alongside a profound sense of betrayal. As in the closing days of the Vietnam War in 1975, the international airport quickly became the epicentre of scenes of chaos and collective panic, as thousands rushed onto the tarmac in desperate attempts to board the last planes out of the country. Queues stretched for kilometres outside the country’s only passport office. It is still too early to tell whether the Taliban’s promises of a more ‘inclusive’ government and amnesty for former collaborators of the Western forces will be met. What is certain is that Western governments owe them safe passage, though, from the announcements coming from Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s office in late August, it seems unlikely this will be properly honoured.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

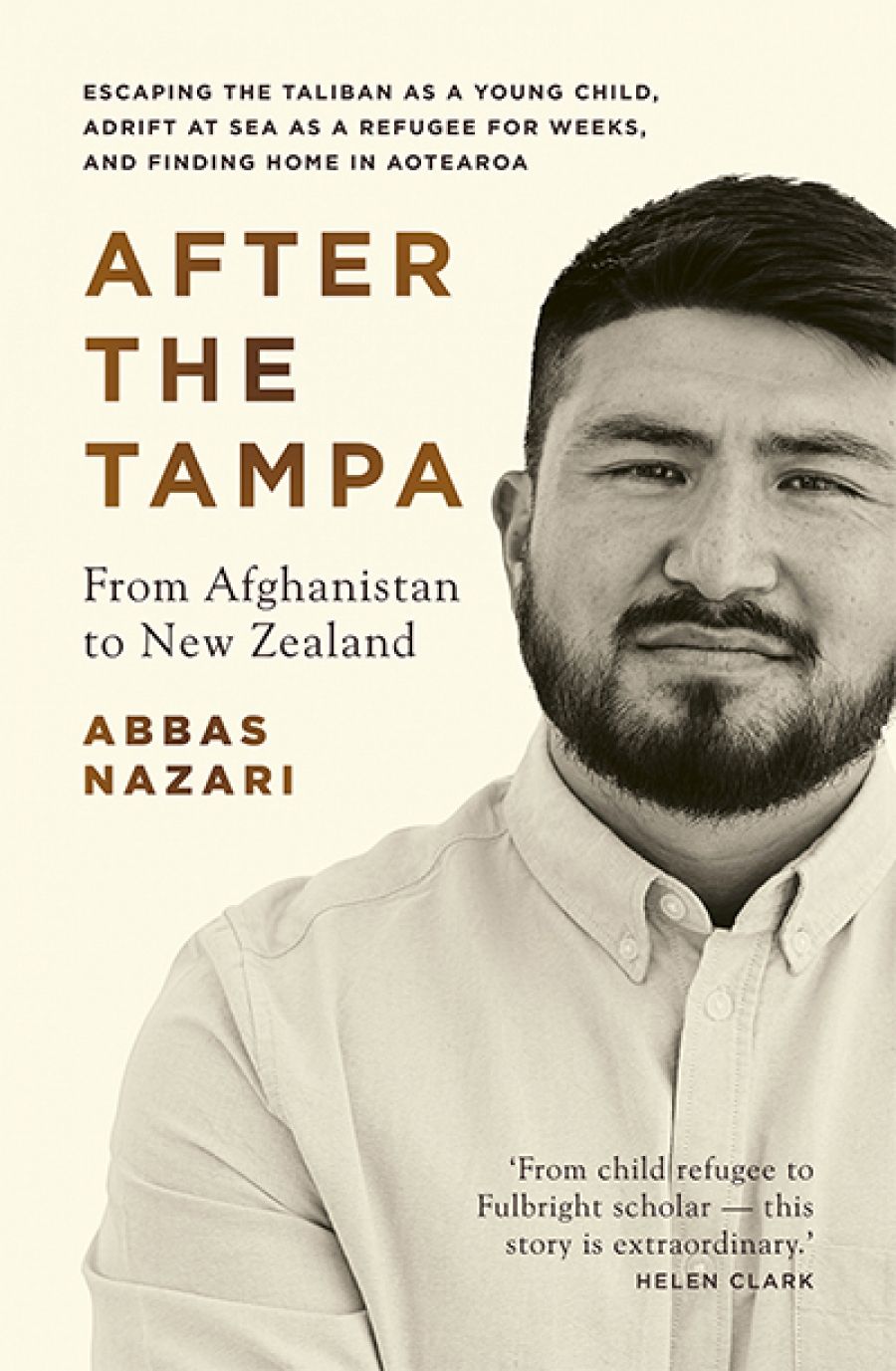

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ruth Balint reviews 'After the Tampa: From Afghanistan to New Zealand' by Abbas Nazari

- Book 1 Title: After the Tampa

- Book 1 Subtitle: From Afghanistan to New Zealand

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen and Unwin, $32.99 pb, 367 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/kjWvMV

Australian governments do not have a good record when it comes to dealing with Afghan refugees, who started appearing in Australia’s northern waters following the Taliban’s first takeover of the country in 1996. They came in small boats at first, transported by Indonesian fishermen to Ashmore Reef, where they waited to be picked up by Australian Customs and Naval vessels and escorted to the Australian mainland. All this changed two decades ago, when the numbers of asylum seekers trying to reach Australia by boat steadily climbed into the thousands. Vigorous chest-thumping by politicians determined to ‘stop the boats’ was accompanied by a new demonisation of asylum seekers as ‘queue-jumpers’, ‘illegals’, and even potential terrorists. By the time the Palapa, a wooden ferry boat carrying mainly Afghan refugees, sank in the vicinity of a Norwegian freighter, the MV Tampa, public sentiment was primed for the militarisation of Australia’s borders.

August 2021 marked the twentieth anniversary of the Tampa, and of the moment when the Australian government under John Howard introduced the hard-line border protection policies that created the now familiar, brutal regime of offshore processing, temporary protection visas, and boat turnbacks. Abbas Nazari, then aged seven, was one of the 433 asylum seekers aboard the Palapa who were rescued by the Norwegian crew of the Tampa in August 2001. Nazari’s family are Hazara, an ethnic and religious minority in Afghanistan that was among those identified by the Taliban as kafir (infidels) in its genocidal campaign to cleanse its newly proclaimed Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. By this point, Nazari, together with his five siblings and their parents, had already endured a harrowing escape from their small mountain village of Sungjoy in the Hindu Kush mountains, hiding in the backs of lorries to get through Taliban-controlled checkpoints, across the border into Pakistan, and, finally, to Indonesia. As they soon discovered, the UNHCR in Indonesia is little more than a shopfront. Less than one per cent of refugees are resettled worldwide; the other ninety-nine per cent can only ‘wait and wait’ as their children grow up in camps and their lives remain in limbo. ‘It’s not like a vaccine rollout, where you know that ultimately there will be enough doses for everyone and a little patience is all that is required,’ writes Nazari. Indeed, at the current rate it will take centuries to clear the backlog of applications for resettlement in safe countries for the millions of refugees worldwide.

‘When we see a trail of desperate people fleeing conflict, perhaps on the television news, we miss the points in time when a parent has to make a life-altering decision on behalf of a whole family. To stay or to go? To endure known misery or to march towards an unknown future?’ Nazari’s parents ‘chose life’ that fateful moment they climbed aboard the Palapa, but it must have seemed like a dangerous mistake in the days and weeks that followed. Nazari describes his terror as a storm beat down on their already broken, sinking boat. Australian coastguard aeroplanes flew overhead then disappeared. In desperation, the women took off their white headscarves and laid them out on the deck, painting them with the letters SOS in engine oil. Unbeknown to the people on board, Canberra was well aware of their existence, but had already spent the past two days trying to convince Jakarta to intervene. The Indonesian government stayed silent. After three days, and no longer able to ignore the large SOS sign on the sinking Palapa’s deck, Coastwatch finally issued the rescue call to ships in the vicinity. The Tampa, a 260-metre container ship owned by Norway’s Wallenius Wilhemsen Lines shipping company, was on its way from Fremantle to Singapore when its captain, Arne Rinnan, responded. Within hours, his crew had executed the rescue of everyone on board.

What followed has become the stuff of history. As television audiences across the globe were treated to the dramatic bird’s-eye image of the hundreds of hunched men, women, and children on deck surrounded by shipping containers, Rinnan was locked in a bewildering and unexpected standoff with the Australian government, which ordered him to stay out of Australian waters while the refugees on board begged him to take them to Christmas Island. Rinnan ultimately took the only rational option. Licensed to carry fifty and now holding 500 people, many of them ill and some unconscious, his ship was now unseaworthy. The closest port was Christmas Island. After four days, as conditions on board deteriorated by the hour under the blistering heat, the Tampa sailed into Australian territorial waters, making its third mayday signal of distress. Canberra responded by sending in forty-five SAS troops, who, in an extraordinary breach of international maritime law, seized control of the ship.

Nazari describes those days aboard the Tampa in minute detail, mapping his ordeal and his impressions against the political events in Canberra. The Tampa had sailed straight into the eye of a political storm. Remote detention centres had become sites of hunger strikes, self-harm, and riots by asylum seekers, who, having fled Iraq’s Saddam Hussein or the Taliban, now found themselves detained in dangerously overcrowded outback prisons. Australia’s borders, so the public was repeatedly informed, were at breaking point under the strain of hordes of boat people appearing on the horizon. The Tampa was the opportunity the Howard government needed to flex its muscle. On 29 August 2001, as the Tampa remained stranded just outside Christmas Island’s twelve-nautical-mile limit, Howard introduced legislation that effectively denied asylum seekers who came by sea permanent protection. The ‘Pacific Solution’ quickly followed: the poverty-stricken island of Nauru was given $10 million in return for hosting a makeshift refugee camp housing Australia’s asylum seekers offshore.

Meanwhile, Nazari writes, ‘we may as well have been floating in outer space’, not allowed to speak to the media and without any connection to the outside world. It is this invisibility that compelled him – someone whose face and whose story were erased from public view – to write this book. As the days passed, the only contact with Australians was with the black-clad soldiers guarding the perimeter of the Tampa’s deck, awash by this stage with faeces and vomit. Finally, after a week, the asylum seekers were transferred to the Manoora, and taken to Nauru. For the Nazari family, Nauru was only a brief stopover: Helen Clark, New Zealand’s prime minister, had offered to take 150 of the Tampa refugees, and the Nazari family were among the lucky few. They landed in New Zealand on 28 September 2001, six months after they had left their home in Sungjoy.

The Tampa was the catalyst for a new politicisation of Australia’s approach to refugees and migration, which has become more and more detached from any commitment to the humanitarian principles underpinning the original convention on the rights of refugees, a convention that Australia proudly helped write and of which it was one of the earliest signatories. For Nazari, it was a moment when his future changed and gave him his ‘happy ending’. Growing up in Christchurch, with the nurturing of a New Zealand education, Nazari eventually gained a scholarship to the University of Canterbury, graduating with a degree in international relations. In 2019, he became a Fulbright scholar at Georgetown University. He is acutely aware that countless others have not been so fortunate. He has friends who have spent eight years in limbo in Indonesia, while others have drowned trying to make the same crossing his family attempted twenty years ago. Many have had their lives destroyed by interminable offshore detention. But he is no advocate of open borders. Instead, the international community needs to address the sources of upheaval and displacement. It is easy, he writes, to look away, ‘as if the residents of distant lands are too far from the reach of help’, or as if ‘ancient feuds’ are not the problem of the ‘civilised West’.

Once again, as I write, Australia is being asked not to look away. Given the history Nazari tells here, it is difficult to be optimistic.

Comments powered by CComment