- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cultural Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

With the centrepiece of its glorious Edmund Blacket building and its noble quadrangle, the University of Sydney is Australia’s oldest and grandest institution of higher learning – an adornment both to its city and to the nation since its foundation in 1852. Less well known, even in Sydney, is that the university is home to a remarkable accumulation of cultural and scientific treasures – some seven hundred thousand artefacts and objects – held within its museums and collections: the Nicholson and Macleay Museums, the University Art Gallery, the rare books collection of the Fisher Library and university archives, and numerous faculty-based research collections.

- Book 1 Title: Into the Light

- Book 1 Subtitle: 150 Years of Cultural Treasures at the University of Sydney

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $89.99 pb, 193 pp

The sesquicentenary of the Nicholson Museum – the first university museum established in Australia – provided the impetus for the present book, offered here as a handsome showcasing of some of the best of the Nicholson treasures, together with selections from the university’s wider cultural and scientific collections. The work of what were previously separate collecting entities is now coordinated by David Ellis, an experienced museum professional (and a noted photographer), who since 2003 has been Director, Museums and Cultural Engagement. His brief is to meet the particular needs of the university communityand to reach out to a wider community of Australians and international visitors. This book is both a celebration and a step in the efforts now being made to promote a greater awareness and understanding of an important Australian cultural asset. Working with a team of specialist curators – Jude Philp, Ann Stephen, and Michael Turner, with David Malouf providing a characteristically urbane introduction – Ellis has edited a stylish volume that opens a window onto collections of remarkable diversity and beauty.

The range of examples, inevitably eclectic, dazzles and delights. I too admired one of Malouf’s favourites, the great head of Hathor from Bubastis in Egypt (c.900 bce), but I also found others of my own: the gathering of Athenian and Italian terracotta vases including a depiction of Eros on an amphora from Lucania (c.400 bce) and another from Athens, the Antimenes Painter’s (attrib.) Dionysos in the Underworld (525–500 bce); a small Cycladic figurine (c.2800–2300 bce), lovely in its simple perfection of form and made to be cradled in the hand; the splendid Adam and Eve (c.1530) attributed to the Flemish painter Michiel Coxcie the elder, and with its two noble figures (depicted at the dramatic moment of their Fall) based on two of the great sculptures of antiquity, the Apollo Belvedere and the Medici Venus; and a wooden reliquary chest (probably Flemish) of St Eloi and St Hippolytus (c. sixteenth century), with its vignettes of the lives of the two saints painted on a ground of the most delectable laquered red.

But if the collections range widely across many different eras, they also help to illustrate an Australian and a regional story with strong representative holdings in the history and development of painting in this country, and with some significant ethnographic materials from Papua New Guinea and the Pacific. Especially important are fourteen bark paintings collected from the Cobourg Peninsula in Western Arnhem Land and first displayed publicly in Sydney in 1878. Recognised now as some of the earliest bark paintings, these depictions of native animals (among them an emu, a turtle, a dugong, and a cassowary) ground the Sydney collection in the long trajectory of Indigenous art and decoration in Australia. That path is nicely traced through various stages and traditions including the Pareroultja brothers, the Arrente artists who followed the lead of Albert Namatjira in using European watercolour to paint their country, and the later paintings and images of political protest, including Marie McMahon’s screenprint poster Aboriginaland, land rights, not mining (1979) and Robert Campbell Jr’s Portrait of Charles Perkins (1986).

While a lack of resources has mitigated against a major and systematic acquisitions program, significant additions continue to be made through gifts and bequests, an honouring of the early philanthropic examples of Nicholson, the Macleay family, and others. In our own day, the Commonwealth Government’s Cultural Gifts Program has been especially beneficial; it was the means by which Sydney brought into its collection a work of the great Emily Kame Kngwarreye; the lyrical painting Untitled (1990), a celebration of country, is from her early canvas period and grew out of her original batik practice.

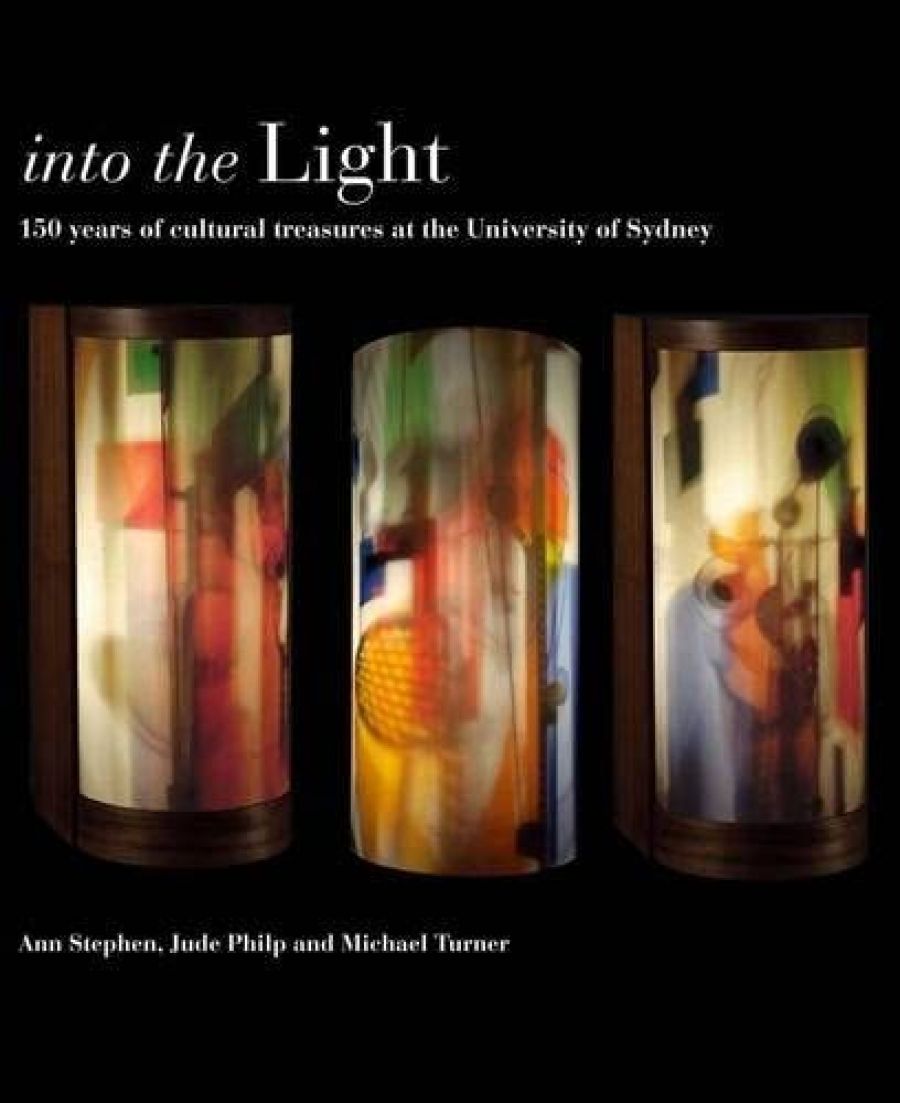

As Ann Stephen shows, the Sydney collection is also rich in other Australian work, in some cases by artists who have had some connection with the university itself as teachers or students. Other works have been acquired as significant exemplars or turning points of various stages in the evolving history of the visual arts in this country. Especially interesting is the strong historical representation of Australian Modernism with examples of work by Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo (a somewhat academic painter himself, but an enthusiastic advocate of post-Impressionism), the young Grace Cossington Smith, Grace Crowley, and Rah Fizelle. But for many, the revelation will be a selection of the astonishingly accomplished Cubist paintings of J.W. Power, who left Sydney as a young medical graduate in 1906 and who later made a twenty-year career as a Cubist in Paris. Power became one of the university’s great benefactors, and provided the means for the teaching and promotion of contemporary art; his generosity was supplemented by his wife Edith’s gift of more than one hundred and fifty of his paintings and more than one thousand graphic works and sketches. Innovation of another kind and from another period is offered in a series of luminal kinetics of Frank Hinder, who, after four decades working between figurative and abstract art, emerged in the late 1960s as one of Australia’s pioneering kinetic artists. His superb Dawson Memorial (1968) is illustrated in its different phases in the book, and provides the striking image on the front cover and the metaphor for the central purpose of this publication.

For just as Hinder’s late work played with light, this book also illuminates an understanding and awareness of a cultural resource which has existed within the (too) narrow confines of the academy. David Malouf remarks that the book is an important first step in making some of the university’s treasures visible outside its own privileged community. But while he would like to see ‘a house or a suite of houses where we could see at last the full extent of them’, there is cause to welcome the radiant luminescence this book brings to a collection that speaks to us across the ages and into our own time and country.

Comments powered by CComment