- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Classics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Unlike China, whose history similarly goes back to the Bronze Age, Europe has been shaped by spectacular collapses and profound renewals, first after the Mycenaean Age and then with the fall of the Roman Empire, which severed what we know as Antiquity from the modern world. The new Europe that emerged from half a millennium of turmoil, cultural regression, and repeated invasion by foreign predators was fundamentally transformed. Its centre of gravity had moved from south-east to north-west; its population was largely composed of former Celtic and Germanic barbarians; its new languages were vernaculars emerging from the pidgin Latin spoken by illiterates; and its religion was Christianity. What made it possible for these originally tribal peoples to build Europe was the blueprint of an extraordinary civilisation, which at first they barely understood, but to which they became the unlikely heirs.

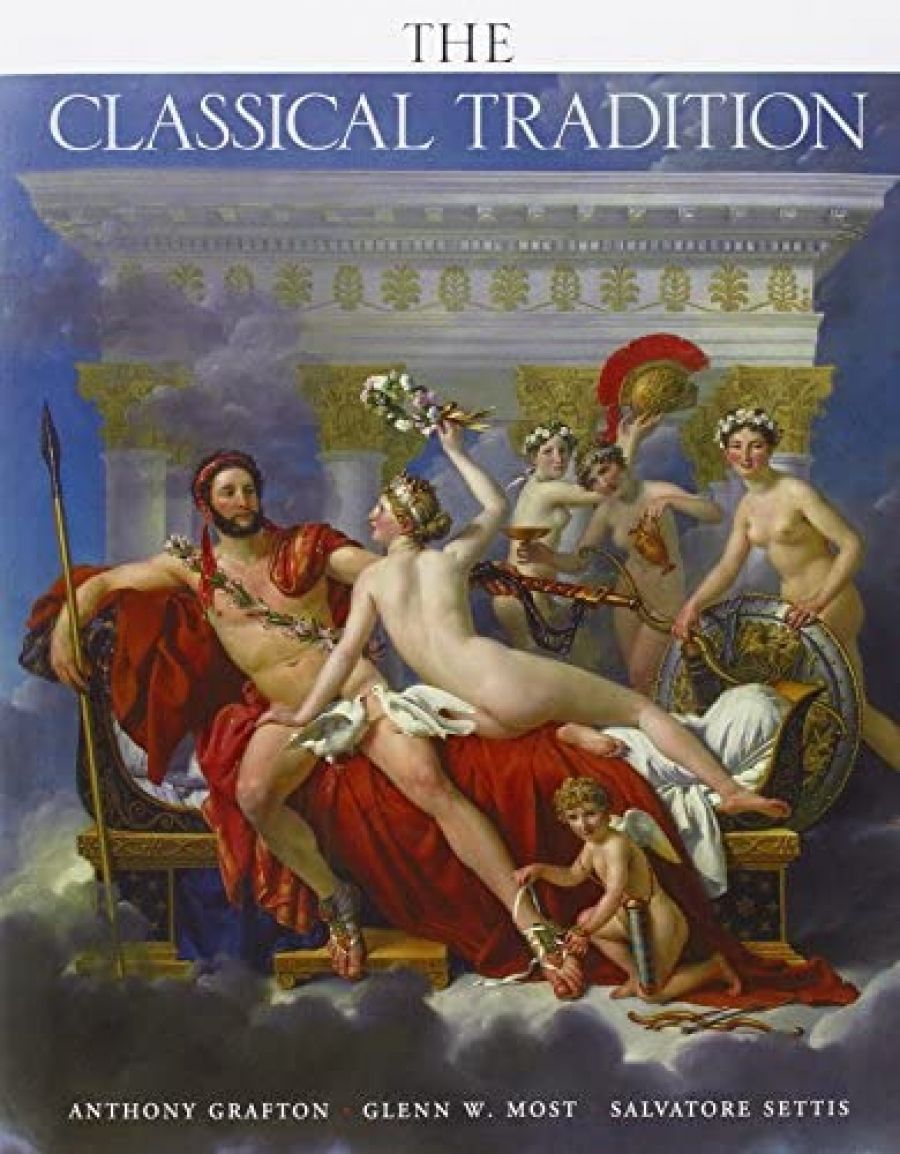

- Book 1 Title: The Classical Tradition

- Book 1 Biblio: Harvard University Press (Inbooks), $69.95 hb, 1088 pp

Thus Europe is a twin civilisation, ancient and modern, the latter constantly referring itself to the former, whether as model and benchmark or, less overtly, as alternative. Antiquity is ubiquitous even in the contemporary world, present whenever we speak of politics, philosophy, history, literature, art, architecture, science, or medicine – all fields in which much of the nomenclature and many of the essential concepts and values derive directly or indirectly from ancient prototypes. It gives some idea of the debt to recall that most of human anatomy was mapped by Galen in the second century ce; that it was not until thirteen centuries after his death that we had recovered a comparable understanding of the body; and that it is only during the last five hundred years that we have been in a position to go further.

Although the relation between these two worlds of our civilisation is so fundamental, it is much less well understood than it should be. This is partly because the question can fall between two stools, especially in the specialised environment of the modern university. Scholars in any modern field will have some idea of the ancient antecedents, but it is often inadequate; conversely, specialists in ancient studies are aware of the afterlife of their subject in a general way, but often take little interest in it. Consider the study of literature: practically all modern writers borrow from and allude to classical authors, just as the ancients borrowed from their predecessors (Virgil from Homer, but Homer also from oral compositions now forgotten). These acts of homage and adaptation, often subtle, are always meant to be appreciated by the reader as a vital layer of the text’s meaning, but teachers and academics today are usually too poorly versed in ancient literature to appreciate the complex play of allusion or to explain it to their students.

It is for such reasons that one can be particularly grateful for The Classical Tradition, a new reference work devoted to the survival and reception of ancient civilisation in the modern period. It addresses precisely the junction that is so often neglected, although its very existence demonstrates that many scholars have in fact been exploring this border territory in recent years. To anyone with an interest in the subjects already mentioned, this book is a veritable Ali Baba’s cave of information not easily found elsewhere, and it certainly deserves a place in every literate library. The colour illustrations included – often excellent, but sometimes rather populist – even seem designed to lend the volume a certain coffee-table appeal. The price, too, is extremely reasonable, given the quality of the contents.

The pervasiveness of the Greek and Roman heritage makes it necessary for The Classical Tradition to cover a vast range of topics: nothing less, in fact, than the world of human knowledge before it was fractured into academic fiefdoms. It also recalls a time when a knowledge of Greek and Latin was indispensable to any kind of serious scholarship. Arranged alphabetically, as in an encyclopedia, entries are devoted to the principal figures of Antiquity and to their subsequent reception – transmission, publication, translation, and interpretation – as well as to important modern scholars who were responsible for such publication and research.

Thus one can follow the story from either point of view: starting with Plato or Sophocles, for example, or on the other hand from Winckelmann, Nietzsche, or his nemesis, the redoubtable Wilamovitz. There are, of course, also thematic entries: thus Theocritus does not have an entry of his own, but is discussed under Pastoral. The index helps us to locate less obvious individuals, as the book generally avoids headings that merely refer us elsewhere, such as Theocritus: see Pastoral. The editors have also chosen not to include footnotes; in some instances one would like more detail on a subsidiary aspect of a question, but generally the articles are carefully designed to cover all the important facts and dates, while including a short bibliography on each topic.

Most of the entries are scholarly, authoritative, and reliable. Here and there, inevitably, readers closely acquainted with a field will find things that might have been better treated: thus Humours, although written by a noted authority, is too short for so important a matter and unclear in its exposition; oddly, there is a separate entry on Temperament; a single more comprehensive article would have been preferable. Ancients and Moderns has some excellent material, but could elaborate on the reasons for the genesis of the Querelle in France, as well as on its importance for understanding later scholars such as Winckelmann. Classical, too, while mentioning the classic–Romantic dichotomy, fails to discuss the classic–baroque opposition in art history. Some important topics, such as Theophrastus and the influence of his Characters – and La Bruyère’s translation – are largely overlooked.

But these are minor criticisms, and omissions can often be made up by cross-referencing to another entry on a related topic. The articles are remarkably well written, precise yet free from jargon, often – like the fine Horace – with character as well as scholarship, and conveying the beauty and enduring appeal of the subject. Best of all, perhaps, the authors write with sympathy and historical imagination, avoiding that odious note of condescension that often creeps into contemporary discussions of earlier periods – whether Antiquity, the Renaissance or the nineteenth century. Even subjects that could be contentious, such as Slavery, Colonization, and Sexuality, are treated with admirable clarity, free of the moralistic smugness of hindsight.

This book repeatedly reminds us that one of the great virtues of classical studies, ever since the fall of Rome, has been as a space of freedom – freedom from barbarian ignorance, from religious bigotry, from moral puritanism, political ideology and materialistic obtuseness. Precisely because they so long predate modern Europe, the classics lend us a perspective that goes beyond the limits of modern society: beyond Christianity and its morality (this, as several authors point out, has always been a tacit attraction), beyond ethnic groups and their tribal cultures, beyond the political and social structures and conventions that most people take for granted. To know the classics, several contributors point out, is to belong to a kind of élite, but, as the stories of so many scholars from modest backgrounds reminds us, it is one whose membership is open to any who care to make the effort.

Comments powered by CComment