- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Features

- Custom Article Title: The astonishing legacy of Sergei Diaghilev

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The astonishing legacy of Sergei Diaghilev

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What is it about the Ballets Russes that resonates with so many people? Is it the magic of a redeemed art ordained in a marriage of artists, dancers, and composers overseen by a master celebrant – Sergei Diaghilev? Is it remembrance of a creative fire that burst onto the stage in 1909 and assured a strong future for ballet around the world? The answer is ‘yes’ to both, but I think that what attracts us most is nostalgia for a particular moment in time; the desire to have witnessed those famous performances in the early decades of the last century.

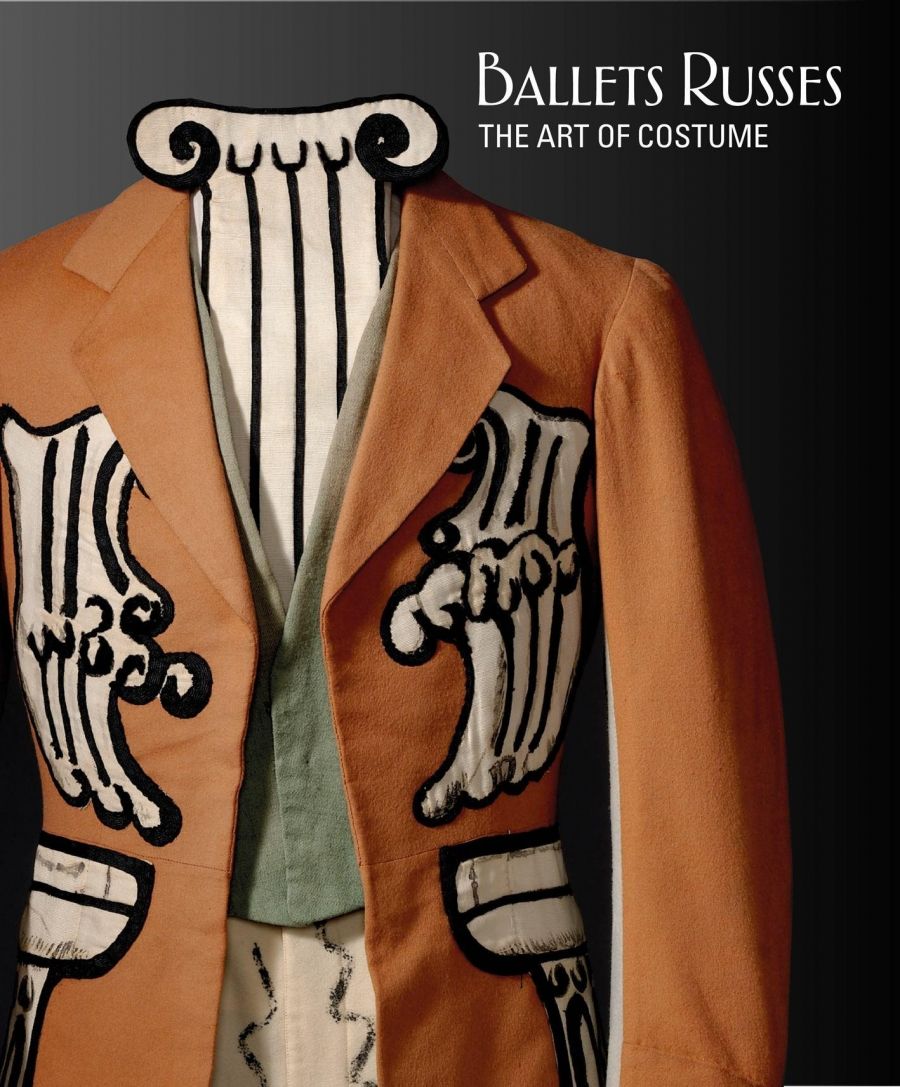

- Book 1 Title: Ballets Russes

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Art of Costume

- Book 1 Biblio: National Gallery of Australia, $39.95 pb, 264 pp

Of all the artefacts – set and costume designs, souvenir programs, and rare photographs of the dancers posing for production shots – nothing conjures up the immediacy and excitement of the dancers and the performances like the surviving costumes. The fact that Ballets Russes costumes are housed in a number of international museum collections is testament to how much they are valued. However, the costumes and sets have a chequered history. When Diaghilev died in 1929, the fate of the Ballets Russes was something akin, in the theatre world, to the breakup of Alexander the Great’s empire after his death. Diaghilev’s company disbanded and a number of new troupes formed and morphed in the following decades. Of those, Colonel Wassily de Basil’s and René Blum’s Les Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, formed in 1932, had the advantage of access to original sets and costumes from Diaghilev’s company.

Earlier in 1931, Léonide Massine, a principal dancer and choreographer for Diaghilev, tried to buy a large number of costumes, sets, and musical scores, but, lacking financial backers, was forced to sell them. They were then acquired by a foundation linked to de Basil’s company. Subsequently, the revival of many of the Diaghilev productions kept sets and costumes together, but in 1951, with the death of de Basil, his lawyer, Anthony Diamantidi, assumed control and tried to raise finances for a new company. This never happened. The costumes and sets were left in a warehouse outside Paris until 1967, when Diamantidi decided to sell the entire collection. Sotheby’s in London auctioned these in three successive sales. The Australian National Gallery (now the National Gallery of Australia) was a principal bidder at the third auction and purchased forty-seven lots, which contained more than four hundred items, including costumes, sets, and props. In today’s money the £3000 paid for the material is laughable, but those who saw the costumes when they first arrived in Canberra might have thought it was money wasted. The costumes were in a wretched state, seemingly destroyed by years of sweat, caked make-up, and mould. Bit by bit they were painstakingly cleaned and restored, giving them a new life at the National Gallery.

Of course, other institutions around the world were engaged in similar activity: conserving, cataloguing, and displaying their collections. As well, sporadic exhibitions over the last eighty years culminated in a virtual orgy of Diaghilev shows focused around the year 2009, the centenary of the first appearance of the Ballets Russes in Paris. A huge exhibition, Étonne-moi: Serge Diaghilev et les Ballets Russes was shared between Monaco and Moscow in 2009, and featured a lavish publication. Tangential but even more spectacular was the State Russian Museum’s Diaghilev Beginning, a look at Diaghilev’s activities before his involvement with the Ballets Russes. The displays included a partial reconstruction of his famous exhibition of Russian portraits held at the Tauride Palace in St Petersburg in 1905. More recently, the Victoria and Albert Museum mounted a major exhibition of its own holdings of Diaghilev material.

For Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes, 1909–1929, the V&A took the purist approach, covering only those years that Diaghilev was alive and leading the company. Running almost parallel to the London show, the NGA’s exhibition includes costumes and designs employed in the period that Ballets Russes companies performed in Australia (1936–40). The result is a compendium, not only of Diaghilev-period material, but also of objects germane to the development of ballet in Australia and to the phenomenal influence of the Ballets Russes’ three tours here.

Ballets Russes: The Art of Costume marks the third presentation of Diaghilev material by the NGA. In 1990 Michael Lloyd, Assistant Director, and Robyn Healy, Curator of Fashion, put together a wonderfully stagy presentation of the costumes restored to date, along with some unrestored material to compare and contrast, which was accompanied by a modest but informative catalogue. In 1999 the National Gallery of Australia, in partnership with the Art Gallery of Western Australia, mounted a far more ambitious exhibition not only featuring additional restored costumes, but also putting the NGA’s collection in context, with major loans from other institutions. This allowed for material from important productions such as Le Sacre du Printemps to be represented, and provided additional costumes and designs for productions such as Le Pavillon d’Armide and The Sleeping Princess. The accompanying publication included essays by scholars from Australia and around the world.

For the most recent exhibition, Ballets Russes: The Art of Costume, the NGA has returned exclusively to its own collection, this time with a far greater number of restored costumes on display. The catalogue, almost three times the size of its NGA predecessor, is a major publication. Although From Russia with Love, the 1998 catalogue, included some full-page details of costumes, the most recent effort abounds in them. These details not only reveal the richness of the materials employed, but also the sometimes roughly applied construction of elements not visible when worn on stage. Illustrated costumes are so well photographed that it is possible to tell that more conservation work has been carried out since their last outing, as with those of the nymphs from L’Après-midi d’un faune.

Heading the team for Ballets Russes: The Art of Costume was Robert Bell, Senior Curator, Decorative Arts and Design at the NGA. In the catalogue, his opening essay ‘The Ballets Russes Costume Legacy’ does little more than sum up the history of the Ballets Russes costumes available in other publications, but in his following essay ‘Wild Dream: Imagining the Ballets Russes’, Bell hits his stride and gives an engaging account of the background to ballet in Russia, Diaghilev, and Mir Iskusstva (World of Art), as well as of the extent, influence, and legacy of the Ballets Russes. Another contributor, Helena Hammond, looks at the Ballets Russes in terms of the classical tradition, which reminds the reader that members of the World of Art movement had a strong and nostalgic interest in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries in Russia and France. In her essay, Christine Dixon questions how much of the Ballets Russes material was actually avant-garde, and dance historian Michelle Potter provides important insights into the marketing and promotion of the Ballets Russes in Australia. However, there are niggling mistakes in the text, such as the references to Sergei Prokofiev as ‘Nikolai’ Prokofiev in Dixon’s essay, and to Antal Dorati as ‘Donati’. These editorial oversights mar an otherwise pleasing publication.

Perhaps the finest contribution is from Debbie Ward, whose descriptive essay, ‘Sights Unseen: Tags, Stamps and Stains’, details the detective work undertaken by the NGA’s textile conservators to identify costumes, dating them, and even determining the kind of make-up worn by the dancers. This builds on an earlier article by Josephine Carter, ‘Conserving Costumes from Les Ballets Russes de Serge Diaghilev’, which appeared in the National Gallery’s 1990 catalogue. Carter was the first to describe the painstaking work undertaken to reveal the secrets of these costumes, some of which had subsequent layers built over originals that have now been restored. Ward’s article describes the continuation of this work. It is clear that the various textile conservators who have worked at the National Gallery over the past thirty or so years are the real heroes of this project.

Comments powered by CComment