- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Features

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Dorothy Hewett is a vivid presence in all her poetry. This selection from her life’s work opens with a poem written in her last year at school.

- Book 1 Title: Selected Poems of Dorothy Hewett

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $29.95 pb, 158 pp

The book concludes with ‘What I Do Now’: at seventy or so, the poet spends an entire cold winter’s day in bed reading Elizabeth Bishop’s letters. ‘Will I live to a great old age?’ she wonders:

there are lots of mad old women

in these mountains

shut up in their houses dying.

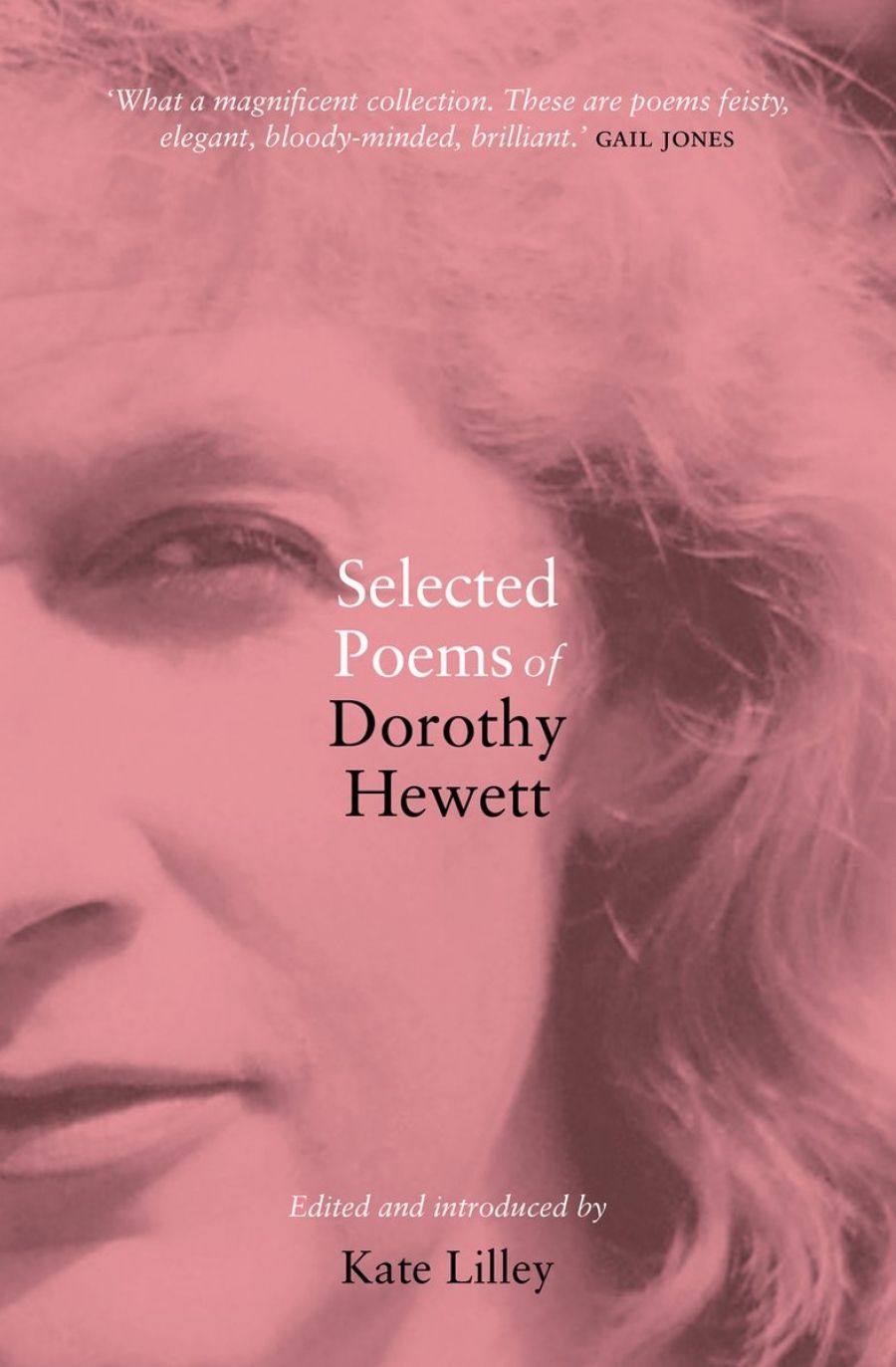

From youth to old age, her poetic personae are intensely self-dramatising, demanding to be noticed, inviting the reader to complicity with their self-fashioning. Yet the voice of the poetry is distanced, observing or remembering the female subject in process – desiring and desired, or mad with the pain of loss. This cool observing eye is captured in the photo portrait on the cover of Selected Poems, a striking design using only the left-hand side of Hewett’s youthful face. It enables her to be at once celebratory and sardonic, giving a sharp edge to the myth-making that she practised with such verve.

Making and remaking legends of her own life became a conscious element of the poetry in ‘Legend of the Green Country’ (1966), where Hewett inhabits an always-ambiguous garden landscape of her family’s farm as ‘Eve, spitting the pips in the eye of the myth-makers. This is my legend … ’ In ‘Living Dangerously’, she casts a sardonic eye on her former self, the Communist Party activist, with other women ‘meeting clandestinely in Moore Park / the underground funds tucked up between our bras, / the baby’s pram stuffed with illegal lit’. She does not confine herself to female figures. Equally powerful is the male persona of the Russian poet, dead in a Siberian prison aged forty-seven, that she projects in ‘The Mandelstam Letters’ series. In the late poems from Peninsula, the ageing body (‘the belly drags / and hugs its pain / it imagines the stump / of the cervix … ’) still harbours the child ‘unreconciled / in a garden closed / on a lost and fabled world’.

The poems question sex, death and politics, but they never doubt the power of poetry. They echo poets from Shakespeare and the King James Bible, through Tennyson and T.S. Eliot (‘what a double!’ she exclaims in ‘Memories of a Protestant Girlhood’), to the American confessional poets of the 1960s. She rings a distinctively female change on Lowell’s ‘Man and Wife’, for example, in ‘I’ve Made My Bed, I’ll Lie On It’:

With legs apart I lie on mother’s bed

disturbing the dust that shrouds the

mighty dead.

You stake me out; as I begin to moan

her hairbrush beats us like a metro-

nome.

These lines from ‘Alice in a German Garden’ pick up the rhythms of Eliot’s ‘Gerontion’ and also its invocation of corruption:

… our American voices echo

Across the borders, harsh with chain-

smoking and endless coughing

In misty gardens: the thirties created us,

McCarthy made us immortal,

The Cold War embalmed us; we creak

in wicker chairs

Under the linden trees in a strange

climate …

Hewett’s poetry has a strong narrative drive, which manifests itself in the extended lyrics that draw on ballad forms and, later, in numbered sequences of poems. The layout of Selected Poems encourages the reader to recognise these sequences, and in her introduction the editor singles out in particular the ‘formidable’ livre composée of Alice in Wormland (1987). At the time this book was published, Hewett wrote: ‘My struggle as a poet has been to wring the neck of rhetoric, to modernise my poetics, and try to catch the moment with a shorter, tougher, economical line, centring on a driving verb.’ Poem 28 from Alice shows this in action:

Alice lives in the age of darkness

beyond Eden’s rim remembering him

that Nim whose changing face

laid waste her garden

nothing flowers in the grim light

they kiss & cling & he is hers

& she is some Cassandra

cursed with second sight …

Poetry is one of many genres that Hewett practised as a writer. There were not only the plays for which she is perhaps best known, but also songs, stories and novels, essays and memoirs. Her life was rambunctious: youthful rebel, communist activist, university lecturer, mother six times over, wife three times over, lover of many. Such experiences fed her lyric and dramatic muse. She became one of the foremost dramatists of her time, with more than fifteen plays and music theatre pieces to her credit. The poetry preceded and paralleled her career in theatre: she was at her most prolific in the 1970s and 1980s, when she published some two-thirds of the poems reproduced in this selection.

Poet and literary scholar Kate Lilley has selected for this book one hundred poems from a total oeuvre of more than four hundred, most of which appeared in the 1995 Collected Poems edited by William Grono. The arrangement is largely chronological, but does not attempt to give equal representation to all the stages of the poet’s writing life. Rather, the selection draws attention to the major themes that persist throughout – sexual desire, memory, intimations of death, political vision, poetic affiliations. Thus the poems ‘constitute a highly-charged but discontinuous Künstlerroman reckoning with Hewett’s strong sense of literary vocation, her life and inevitable death as an artist’. The introduction illuminates the key features of Hewett’s art, her ‘claiming the power of poetry as memorial inscription and linking it to sexual energy, marking and forestalling the passing of time and its corollary, loss of presence’.

The book is an extraordinary act of editorial artistry. It also represents a long labour of love and mourning, for Dorothy Hewett was Kate Lilley’s mother. Before her death in 2002, Dorothy asked Kate to edit a Selected Poems. It was a big ask, I imagine. Kate had read and heard the poems all her life, sometimes typing them for Dorothy or helping her to edit them. Now she had to immerse herself in them, and make choices. She writes: ‘I didn’t quite know how difficult it would be to bring my judgement to bear on Mum’s work; to make the final choices without being able to talk to her.’ In undertaking this task and bringing to it her own poetic skill and insight, Kate Lilley has achieved not only a generous-hearted sharing of the gifts that Dorothy Hewett bequeathed – ‘a body of work full of interest and personality, riven with contradiction’ – but also a fulfilment of her mother’s wish. The concluding statement of her introduction gets it exactly right: ‘As we read, we are right there with her, where the poem is, where she wants us to be, keeping her alive.’

CONTENTS: MARCH 2011

Comments powered by CComment