- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bani’s story

- Article Subtitle: Michael Mohammed Ahmad’s new novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Bani Adam returns as the narrator–protagonist of Michael Mohammed Ahmad’s The Other Half of You, a sequel to his two previous books. The most recent one, The Lebs (2018), gave us the story of Bani’s teenage years at Punchbowl Boys’ High School: the trials of a Lebanese Muslim boy in a majority Lebanese Muslim community nestled inside the larger, diverse territories of Western Sydney, in post-‘War on Terror’ Australia. The Other Half of You is an account of Bani’s late teens and early twenties, and of an inner conflict between religious, cultural, and romantic pieties.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

%20copy.jpg)

- Article Hero Image Caption: Michael Mohammed Ahmad (photograph by Anna Kucera)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Michael Mohammed Ahmad (photograph by Anna Kucera)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Shannon Burns reviews 'The Other Half of You' by Michael Mohammed Ahmad

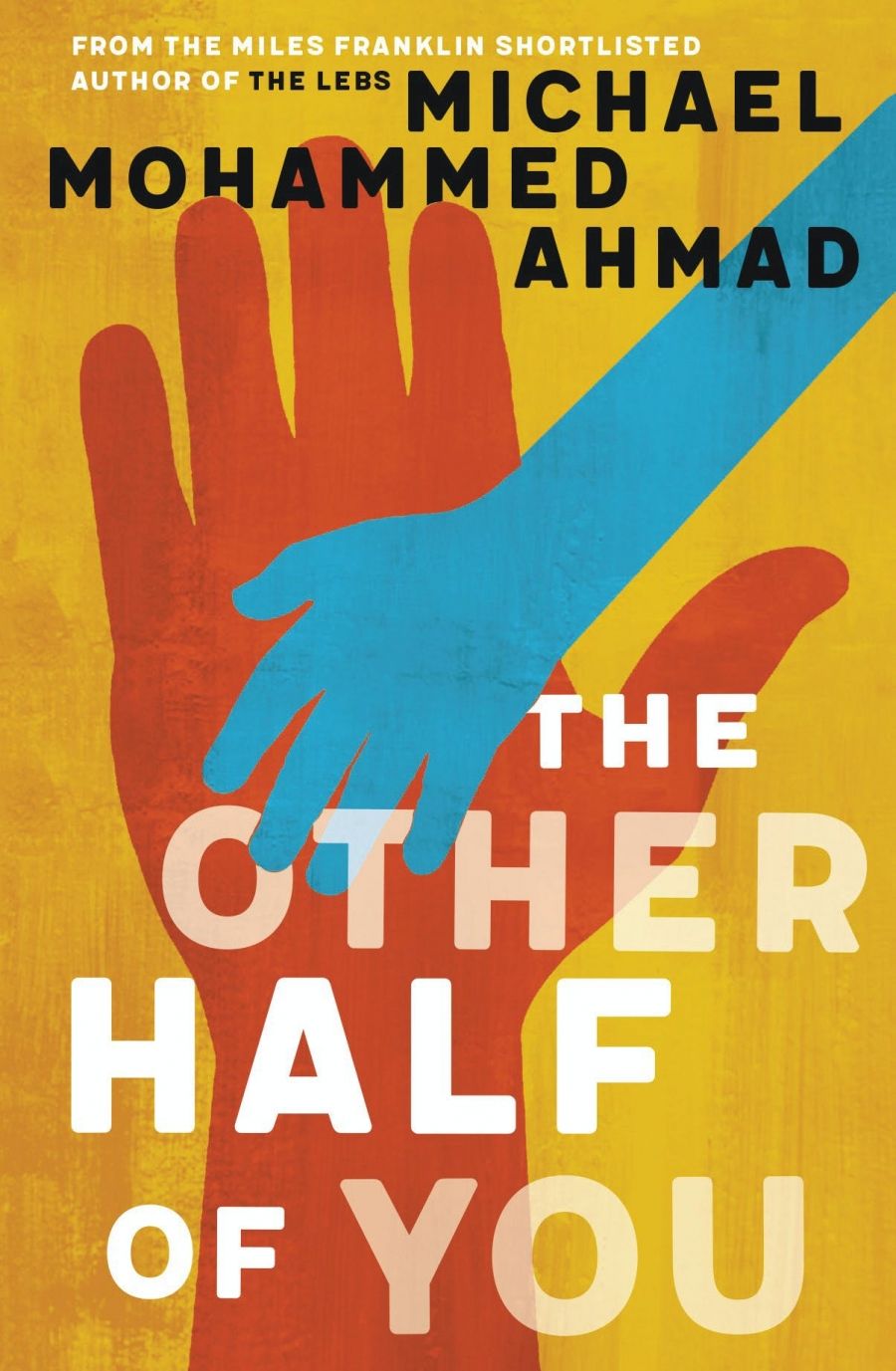

- Book 1 Title: The Other Half of You

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette Australia, $32.99 pb, 339 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/qnAMBb

The Lebs left considerable room for readers to register ironic self-awareness and comedic intent, but The Other Half of You is not so open-ended. Bani’s story is related to his child as family history and a form of paternal wisdom. It employs a How I Met Your Mother-style structure for the first two-thirds, and the narrating Bani is largely sympathetic to his younger self. This form of narration, combined with heightened prose inspired by the great literary love stories – Anna Karenina, Romeo and Juliet, Madame Bovary, Layla and Majnun – pushes the novel in the direction of sincerity. Though playful and irreverent at times, it is primarily a story of a ‘star-crossed love’ constrained by circumstance.

Bani lives with his parents while attending university (he is the first in his family to do so), and he stays with them into his early twenties, diligently saving money while working in the family shop. His father has promised to buy him a ‘McMansion’ after marriage, as long as he does what is expected of him. Bani spends his evenings reading and training (he is a boxer), but is troubled by his future prospects. Since he is unwilling or unable to challenge his father’s authority and thereby risk squandering the securities that conformity promises, he is destined to marry a fellow Alawite Muslim and submit to the cultural traditions or ‘scripts’ that are dominant in his community.

This is particularly distressing because Bani is in love with a young Lebanese Christian woman. The romance remains chaste, but Bani calls her every two hours (‘I needed to know she was safe’). When she goes to the cinema without him, Bani phones her twenty-six times. This demonstrates an unpromising level of obsession verging on possessiveness, but there is no clear sign that the older, narrating Bani is aware of this. A similar pattern is repeated throughout: behaviour that seems designed to demonstrate Bani’s heightened sensitivity and romantic devotion has the effect of suggesting that he is unwell.

When Bani learns that a prospective Alawite wife, Zainab, has lost her father and financial security, he feels a sudden desire to ‘care’ for her. He wanted to be her protector, Bani tells us, yet he is enraged when Zainab asks him to reject her so she can be with her Australian boyfriend: ‘I wanted to puke in Zainab Abdullah’s face, not for dishonouring the memory of her father ... but for using me.’ One moment he is willing to sacrifice his own interests to rescue a vulnerable person, the next he is repulsed by her request for such a sacrifice.

There are numerous opportunities to register satirical intent in such a novel – for the author or narrator to signal that his protagonist’s inconstancy, deluded self-image, and extreme responses to mild difficulties are an important focus of the story – but that doesn’t happen.

The most telling demonstration of Bani’s character centres on a poem and two sandwiches. First, he introduces us to ‘Bani Adam’ (or ‘Son of Man’), a poem written by the thirteenth-century Persian writer Saadi Shirazi. The poem argues that attentiveness to other people’s suffering is humanising, and that whoever fails to recognise that suffering thereby loses their humanity. Soon after, Bani’s new wife, Fatima, makes him an uninspired sandwich. He feels sorry for her, assuming that even sandwich-making is beyond her limited capacities. But when he sees that she has prepared a far superior sandwich for herself, Bani feels as though he has been ‘punched in the face’. He then describes Fatima watching Friends while delighting in her snack, unaware of his anguish: ‘She chewed and laughed and chewed and laughed and chewed and laughed, the name of the human unretained ’ [my italics]. Because Fatima has taken more care preparing her sandwich than his, she loses her humanity in Bani’s eyes. This is a frequent rhetorical manoeuvre in The Other Half of You: small events are bizarrely amplified. The strategy is well suited to comedy, but Ahmad conjures something closer to melodrama.

Bani inherits a fidelity to authenticity from his father, who is a ‘real man’ and a ‘real Arab’ because he fulfils the prescribed religious and familial duties, but Bani transfers this concern with ‘realness’ into other domains. For him, there is such a thing as a real Western Sydney voice, which is sometimes mimicked or ‘stolen’ by others, like his former English teacher, who published an award-winning Young Adult novel. Unlike her, Bani is a real product of Western Sydney, who speaks with the authority of local experience, yet his markers of authenticity are unfailingly cartoonish: racist and sexist language, alongside a fondness for McDonald’s and KFC.

Bani’s passion for fast food takes on deep significance. His message to the eventual mother of his child is: If you can’t respect my love of KFC, which is connected to my upbringing, you can’t love me. Bani is not ready to put away childish things, so he transforms them into sacred markers of identity and asks that they be recognised as such. The reiterated link between fast food and authenticity would produce a clear, undercutting irony in a different kind of novel – signalling that Bani’s notion of ‘realness’ is the conceptual equivalent of cheap, mass-produced comfort food – but The Other Half of You embraces its schlock unironically.

Comments powered by CComment