- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Impassioned and violent

- Article Subtitle: A panoramic view of a largely misunderstood era

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

William Darrah Kelley – a Republican congressman from Philadelphia – stood at the front of a stage in Mobile, Alabama, watching as a group of men pushed and shoved their way through the audience towards him. It was May 1867, Radical Reconstruction was underway, and Southern cities like Mobile were just beginning a revolutionary expansion and contraction of racial equality and democracy. The Reconstruction Acts, passed by Congress that year, granted formerly enslaved men the right to vote and to run for office in the former Confederate states. Northern Republicans streamed into cities across the South in 1867, speaking to both Black and white, to the inspired and hostile – registering Black voters and strengthening the already strong links between African Americans and the party.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Samuel Watts reviews 'The Age of Acrimony: How Americans fought to fix their democracy, 1865–1915' by Jon Grinspan

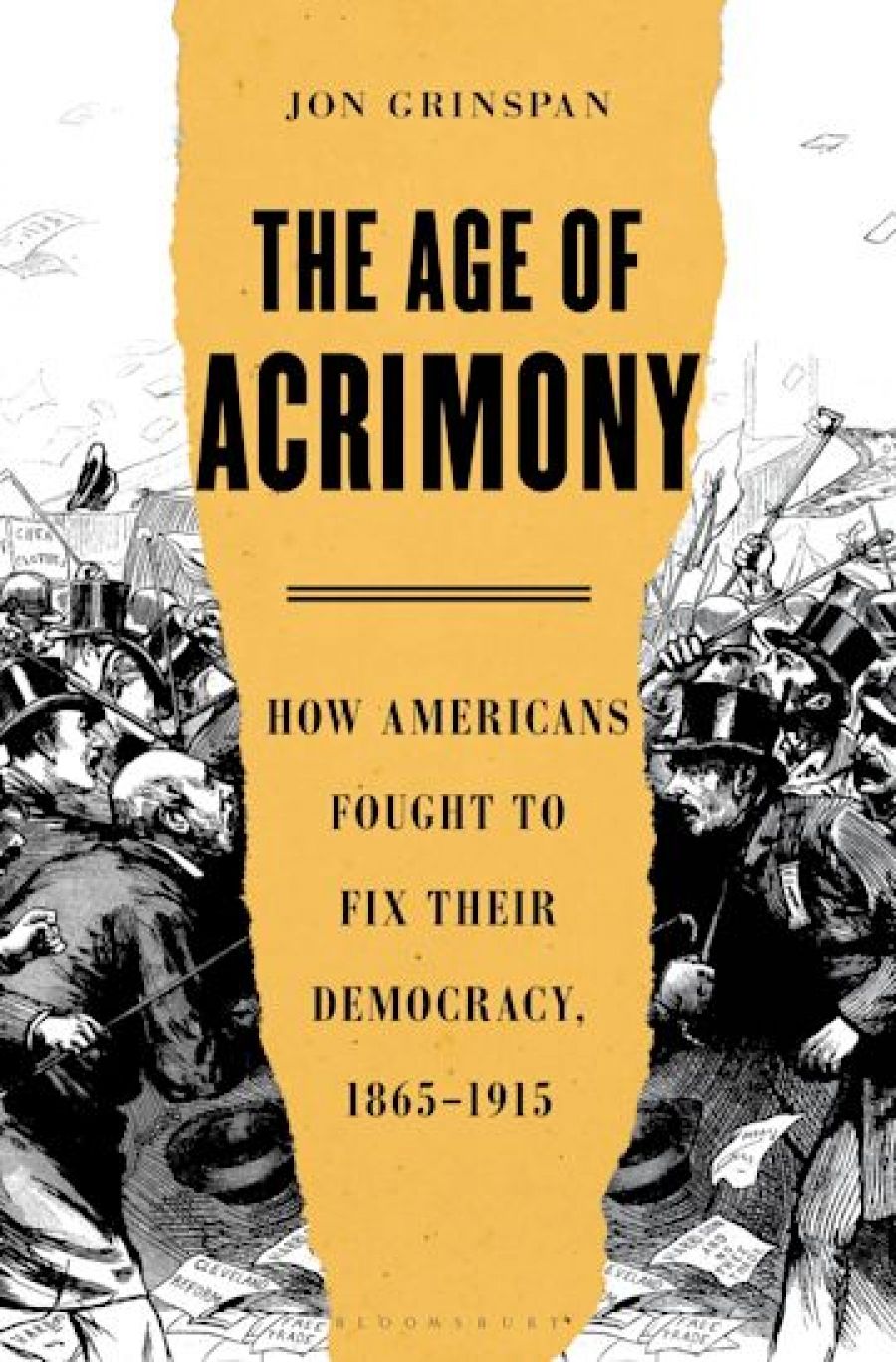

- Book 1 Title: The Age of Acrimony

- Book 1 Subtitle: How Americans fought to fix their democracy, 1865–1915

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $64.99 hb, 382 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/n1NMjR

Some four thousand Mobilians had come to the Old Courthouse steps that night to watch ‘Judge’ Kelley speak about civil rights and Reconstruction. Kelley stared down at the gang of men who had begun to taunt and heckle him. Kelley – thin, tall, and light on his feet – could stride across a stage and project his deep, grumbly voice in concert halls and open fields. Kelley’s skill on the stump was matched by his passion for data and facts that elevated his rhetoric and even impressed his enemies, some of the time. The approaching men were there to humiliate and frighten Kelley. They yelled, ‘Take him down! Put him down!’ to which Kelley, leaning over the makeshift stage, replied: ‘I tell you that you can not put me down … I am not afraid of being put down.’ Then the shooting started. Kelley dived behind the speaker’s table, as no fewer than sixty-five bullets were fired in his direction. Chaos ensued, the crowd scattered, and Kelley was rescued by two Black Mobilians, who quickly escorted him back to his hotel. Two men were killed, and many more injured in the shooting.

Jon Grinspan’s captivating new account of American politics in the mid to late nineteenth century is rich with examples like this that highlight the impassioned and violent business that was democracy in the post-Civil War era. Focusing on William Kelley and his daughter Florence Kelley, Grinspan traces what he identifies as a forgotten yet crucial political dynasty in American politics. Kelley, who came from nothing, worked his way up from apprenticing as a watchmaker when he was a child to making speeches as a young man and joining first the Democratic then the Republican party. He was independent to a fault, publicly attacking what he saw as the Republicans’ increasing disregard for the working poor from the 1870s onwards, all the while campaigning for African American civil rights and women’s suffrage. Kelley was particularly devoted to Florence, fostering in her a passion for social justice that would stay with her for life. She would inherit her father’s intelligence and drive, studying at Cornell before leaving the United States to take up graduate studies at the University of Zurich, where she would plunge herself into revolutionary politics, corresponding often with Friedrich Engels. As Florence grew, her politics mellowed, yet she never stopped working. She became an active social reformer, the first female factory inspector, an anti-child labour activist, and a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

One of this book’s many strengths is its ability to recreate the loving and occasionally strained relationship between father and daughter from the letters they wrote to each other. This approach allows the reader to see the Kelleys and their advocacy in a less heroic and more complex light. For example, although Grinspan attributes the death of Reconstruction not to politicians but rather to the moral ambivalence of millions of white voters across the country, he highlights how Kelley betrayed Black Americans by giving up completely on the cause of Reconstruction less than a decade after he had defended it in Mobile.

The Age of Acrimony is not a family biography, but rather presents a panoramic view of a largely misunderstood era of American politics and public life. At the centre of this study, Grinspan places William and Florence Kelley – two close family members whose battles to improve American democracy would highlight a major shift in the nature of American politics and public life. While the political fever that captivated and inspired Americans for the two decades after the end of the Civil War would often lead to brutal violence, intimidation, partisanship, and corruption, it also meant mass voter participation, particularly among African Americans, poor whites, and recent immigrants. Progressive-era reformists like Florence would push through reforms that undoubtedly made American democracy fairer, yet, Grinspan argues, they also suppressed participation – particularly among non-white and immigrant populations – replacing the power of the masses and the rollicking political campaigns of the 1860s and 1870s with the power of wealthy élites and an increasingly powerful executive branch.

Grinspan’s study is, to some extent, a thoughtful defence of a mass political culture that inspired many to believe they could remake American democracy through partisanship and parades – one that is often only considered in terms of the violence it inspired or its failure to realise the lofty goals of Reconstruction. Grinspan is, however, unflinching in his portrayal of the ugliness of campaign politics in this era, when the nation was deeply divided and elections, as in 1876 or 1884, were decided by the smallest of margins and produced a deep-seated bitterness, one that may be familiar to contemporary readers. Progressive-era reforms helped soothe this bitterness and set the tone for a more restrained model of democracy, where participation was reduced to the voting booth and popular culture was increasingly disconnected from electoral politics. Some may find fault with the breadth of this argument, while others (like myself) may want more detail about other factors that separated partisan politics from popular culture – what of technology, consumerism, or the Confederate mythology? Yet, Grinspan’s deep engagement with his sources and his ability to immerse the reader in a rich world of politics, street theatre, and violence, all the while tracing a compelling argument about the shifting nature of politics and populism, is both enjoyable and persuasive.

Grinspan rightly avoids allusions to politics in the present, focusing instead on evoking a social and political world that is often profoundly foreign to contemporary audiences. If there is one lesson about the contemporary era that the author hopes to instil in the reader, it is that the political 'normalcy' that Donald Trump so effectively disrupted in 2016 – with its accepted conventions and behavioural restraints – has not always been normal. Violence and disorder have characterised American democracy throughout history, and while the intrusion of hyper-partisan politics into everyday life and culture may feel novel, it is actually a return to an earlier political norm. In highlighting the violence and corruption of the nineteenth century and emphasising the increasing distance between politics and ordinary Americans (and the growth of Jim Crow) in the twentieth century, Grinspan thus warns against nostalgia. Making America great again seems impossible, making it great perhaps not.

Comments powered by CComment