- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: True Crime

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The fertile fact

- Article Subtitle: An absorbing history in the round

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Musing upon the art of biography, Virginia Woolf bemoaned the constraints that facts imposed on imagination. It is the most ‘restricted’ of all arts, she wrote, limited by ‘friends, letters and documents’. Yet these very restrictions can inspire creativity. Good biographers don’t just accumulate facts; they give us, in Woolf’s words, ‘the creative fact; the fertile fact; the fact that suggests and engenders’. Biography, done well, Woolf concluded, does ‘more to stimulate the imagination than any poet or novelist save the greatest’. By this definition, Julia Laite is indeed a superb biographer.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Alecia Simmonds reviews 'The Disappearance of Lydia Harvey: A true story of sex, crime and the meaning of justice' by Julia Laite

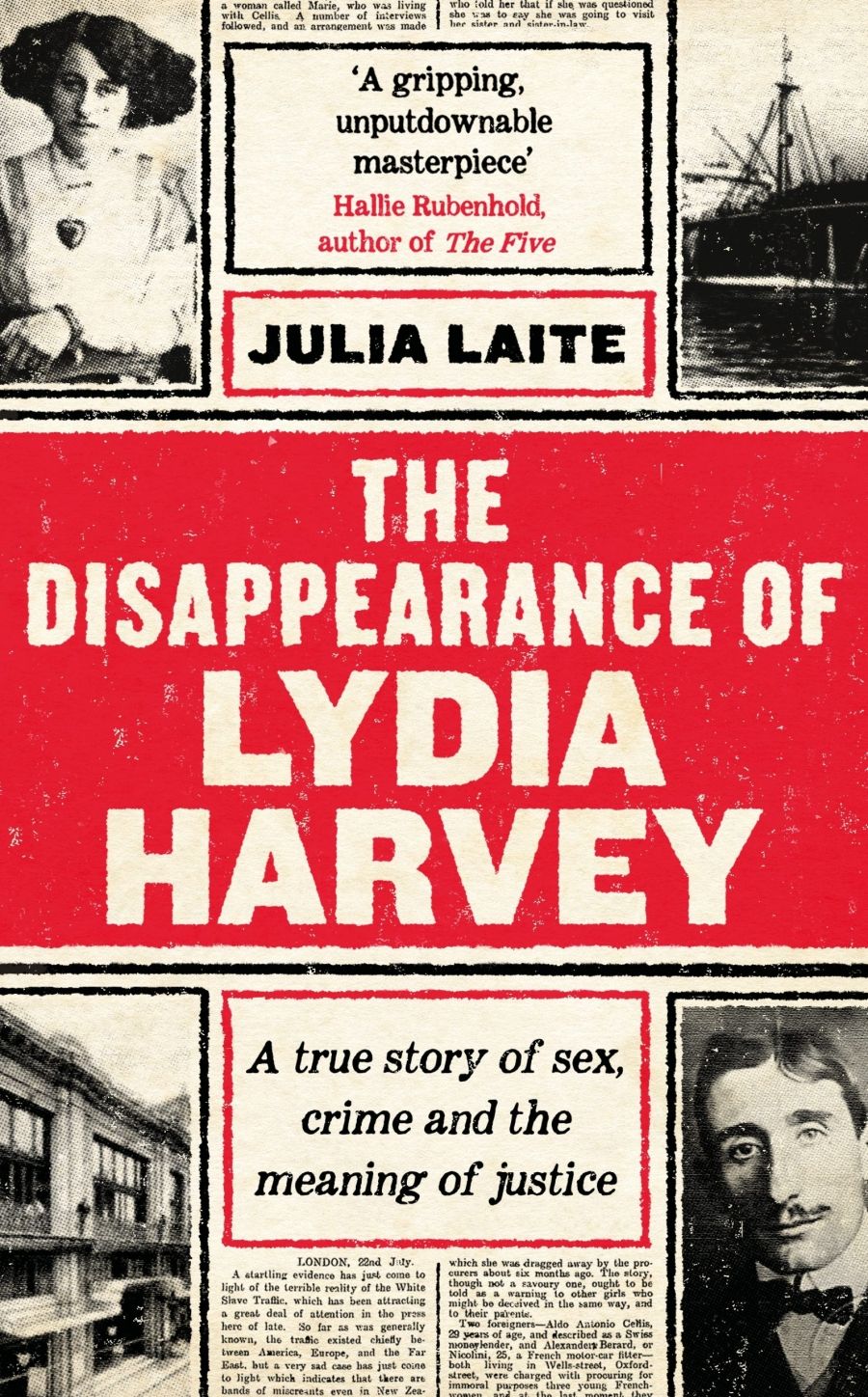

- Book 1 Title: The Disappearance of Lydia Harvey

- Book 1 Subtitle: A true story of sex, crime and the meaning of justice

- Book 1 Biblio: Profile Books, $34.99 hb, 424 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/e4qzaZ

The Disappearance of Lydia Harvey is history at its most rigorous and imaginative. Laite provides an insightful account of the regulation of sex trafficking in the early twentieth century and an enthralling encounter with some of the people involved in one of its more salacious episodes. Laite has described her book as a ‘polyphonic history’ or ‘history in the round’. Each chapter provides the life story of a character involved in Lydia Harvey’s case, moving from Lydia, the victim of trafficking, to the police officer, the journalist, the social worker, the two traffickers, and, finally, Lydia’s family. None of these characters left behind any diaries or letters, yet Laite manages to create a fertile inner world for each person, resulting in a history book that often reads more like a novel, and that challenges the clichés of villains, victims, and heroic rescuers that dominate writing on sex trafficking.

The book begins with sixteen-year-old Lydia as she moves from her home in Oamaru in New Zealand to Wellington, to the glittering streets of Buenos Aires, to the grime of London. This is not, however, a story of a cosmopolitan adventuress in the age of steam, but an examination of what mobility looks like for someone whose movements are compelled by poverty, trickery, state coercion, and a woman’s audacity to dream of something better. Like so many other poor women in regional areas at this time, Lydia first moved to the city to work as a domestic servant, and then as a shop assistant in a photography studio. While living in a boarding house, Lydia met Italian migrant Antonio Carvelli, a man of fascinating manners and a waxed, twirled moustache, who encouraged her to accompany him to Buenos Aires to work in the city’s burgeoning sex trade. On her arrival, Lydia inhabited a nightly world of pawing men, rundown apartments, police raids, and disease. When she contracted gonorrhoea, a decision was made by her traffickers to leave Argentina for London. Chapter One ends with Lydia – ill, emaciated, unwashed, and unpaid – meeting a police officer in Piccadilly who presents her with an image of Carvelli. By confessing that she knew him, Lydia triggered the series of events – police reports, an appearance as a star witness at a trafficking trial in the Old Bailey, and the rescue efforts of social workers – that led to Laite’s finding her record in the Metropolitan Police files.

It would have been easy for Lydia’s file to have been incorporated into a history of sex trafficking in the early twentieth century, a period when modern, international conceptions of trafficking were being codified in law. In different hands, Lydia might have suffered yet another disappearance, this time a historiographic vanishing into a sweeping social history. I have no doubt that such a book would have been worthwhile. Like the book that Laite ended up writing, it would have explored the relationship between women’s licit and illicit labour – how an unliveable wage and physically arduous conditions fed into women’s decisions to enter sex work. Lydia might have been a small case study of the gendered and racialised discourses that circulated around the anti-trafficking movement (victims must be white, passive, and sexually innocent, and predators must be non-Anglo-Saxon). Or Lydia’s story could have demonstrated how a problem that was framed in the press as being about women’s vulnerability to sexual exploitation was enshrined in law as a problem of crime, the regulation of mobile labour and policing of women’s sexuality at national borders. As I write this, I find myself alternating between ‘was’ and ‘is’ because most of what this history illuminates continues to be a problem today.

What is exceptional about this book is that these general themes are explored through the people’s actual experiences. Laite moves deftly between internal and external conditions. How does Laite give her historical actors psychological complexity while staying true to the historical record? ‘In the places where I cannot know or even glimpse what happened or why,’ Laite tells us at the beginning of the book, ‘I have carefully deployed the historian’s tool of “maybe”, “perhaps” and “must have”.’ A good example of this is the moment when Lydia arrives in Uruguay:

How did Lydia Harvey feel as she walked down the gangplank onto that foreign shore? Was her sense of adventure running high, her heart racing with excitement? Or had the gravity of what she’d done begun to set in, amid the swirl of strange faces and unknown languages in Montevideo’s old and overcrowded port? ... Chorus girls looked for theatre managers’ representatives, farmhands sought out the men that the ranger had sent, domestic servants scanned the crowd nervously for their new mistresses.

Here, the disciplined use of historical imagination allows us both to see and feel the world as Lydia might have, and to place Lydia within wider historical processes. Through serial questioning, Lydia is given affect and emotion. Does her heart race with excitement or, alternatively, thud with dread? Seeing the world through Lydia’s eyes also gives us a double vision of history – chorus girls, farmhands, and domestic servants were part of the clamour of the docks, but they were also a cadre of exploited migrant labour. Lydia was saved because sex trafficking, with its gendered messages about the dangers of women leaving their sphere and the need for border control, was an easy crime for early twentieth-century society to rally around. But in this scene we have all the other forms of migrant abuse that were and still are socially sanctioned.

The characters also come to life through an attention to material culture. Laite takes seriously the things that things say. Alive during the transition from a nineteenth-century society of producers to a twentieth-century society of consumers, Laite’s characters use the new world of commodities for self-fashioning, to distinguish themselves from the crowd. As Warren Susman has argued, this new version of subjectivity or self was unmoored from nineteenth-century notions of 'character' – with its emphasis on obedience to moral and social norms – and aimed instead for self-gratification and self-fulfilment through consumption. ‘What must it have felt like to slip on the clothing they had given her, and to feel the soft, light fabric of crêpe de Chine or chiffon against a skin that was used to wool and cotton?’ Laite asks in a scene where Carvelli is attempting to entice Lydia away to work with him in Buenos Aires. Historical imagination here extends to the senses – silk stockings feel like butter, and knee-high boots sparkle with polish – and this sensuous enchantment is as much a reason why Lydia boarded the steamer with her traffickers as the absence of any alternative decently paid work available to women. Inspired by scholarship from the ‘new materialism’, Laite's focus on the vibrancy of objects upsets the subject/object dichotomy at the heart of Enlightenment thought and shows the power that things have over us. But Laite does not stop there, reconciling this approach with the old materialism of Marxist analysis. A sexed labour market, low wages for migrants, or 68-hour weeks for domestic servants mean that this early twentieth-century world of abundance was beyond the reach of the poor. It is an analysis that helps to make sense of the decisions made by both the people who trafficked and the victims of trafficking.

Historians, for too long, have only permitted the bourgeoisie to have inner lives – a diary and personal correspondence have been prerequisites for interiority. Yet as Laite demonstrates, there are other ways of doing history: restrained speculation, thick description, a focus on material culture. They offer voice and agency to those usually defined by mute passivity. Weaving together micro- and macro-history, as well as local, national, and global forces, Julia Laite’s book is, in Virginia Woolf’s words, a masterwork of the ‘creative fact’.

Comments powered by CComment