- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Closer

- Article Subtitle: Chaos and coming of age

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

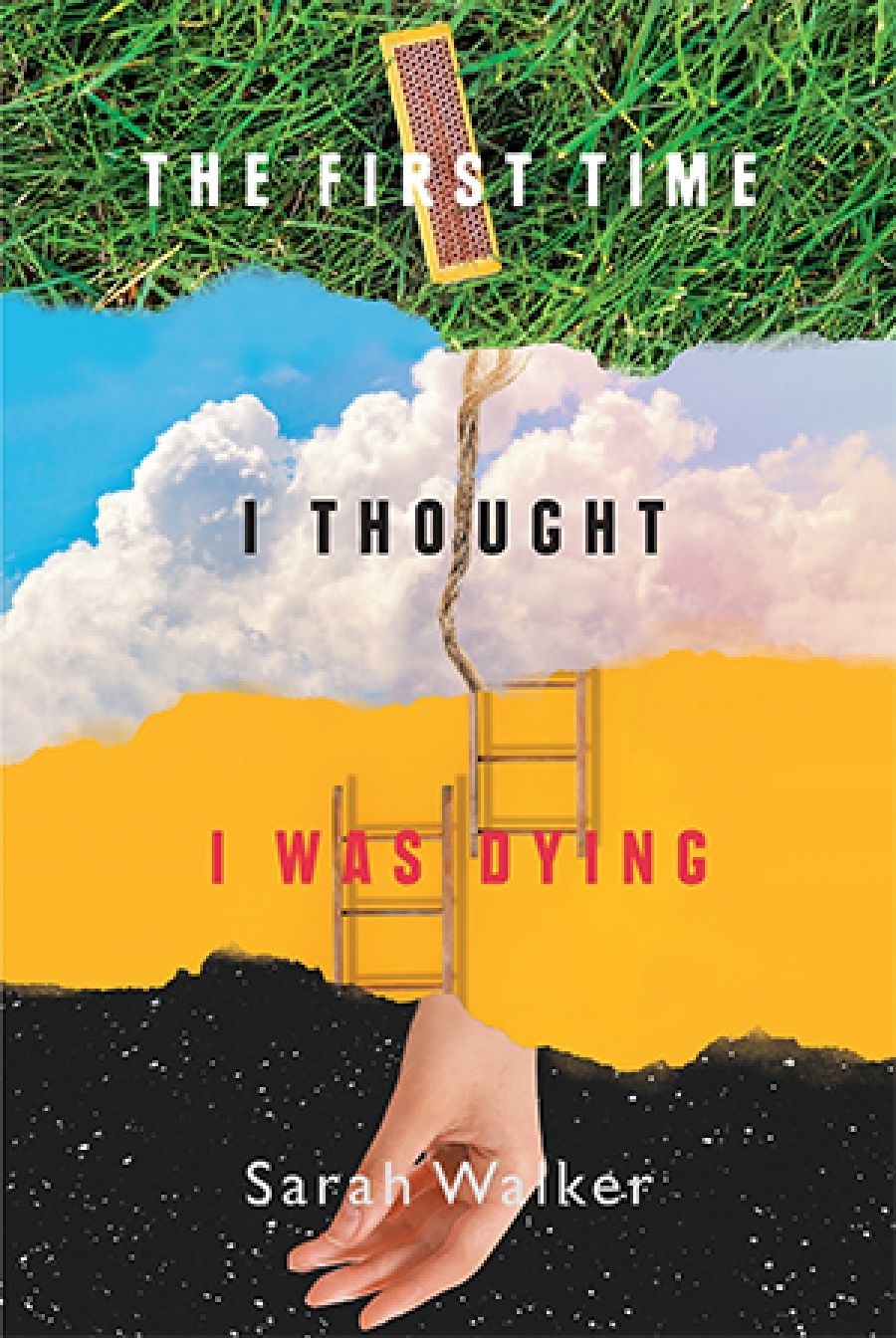

In The First Time I Thought I Was Dying, the photographer–artist Sarah Walker brings into focus ideas about anxiety, control, bodily functions, and the uses of breached boundaries. The essays of this book are personal, and readers of confessional non-fiction will delight in their tone: equal parts jocose and sincere.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Sarah Walker (photograph by author)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Sarah Walker (photograph by author)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Kate Crowcroft reviews 'The First Time I Thought I Was Dying' by Sarah Walker

- Book 1 Title: The First Time I Thought I Was Dying

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $29.99 pb, 224 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/ORnqyG

The collection opens with the lies of the camera and the filtered images that form the mainstay of social media content. Walker takes a position as a professional photographer and speaks to the ethics of her work in a digital ecosystem that seeks to dissolve tensions between the real and the fantastical. She notes the vanishing point of a wrinkle; the partnered men who see her self-portraits and message her to assess her willingness; how Stalin edited out party members. ‘To control the image is to control history.’ An eating disorder serves an early agenda: ‘the world might be chaos … but I would run a tight ship’. At times, Walker slips from view inside her own lens: ‘Every drug story is boring’; ‘The weight dropped etc etc. Plateaued etc etc. I doubled down etc etc. You know this story. You’ve heard it before.’ Fortunately, these obfuscations are rare.

The difficulty of the subject matter speaks to the book’s core thematic: abject unravelling and the lessons held therein. The essays endorse a Rilkean ‘let everything happen to you’ mode of being in the world. Early forays into gym membership, ‘wandering like a displaced ghost between the bewildering machines’, make way for the university years, where she ‘gorged on sex and food with the fervour of the starved’.

The forms of beauty celebrated here are unconventional, and the book is remarkable for that. Walker sees the ostensibly ugly anew. This is part of the methodology that underpins her work as a practising artist: the angles shift flexibly, and while they remain anchored in the quotidian, the takes are different. Having squeezed a pimple, its ‘taunting white nub on the swollen red skin, creamy and perfect, like a glazed donut’, she emerges from the bathroom. Her father’s jovial asides offset the lyric mood as from the wings: ‘Was it a mirror splatterer?’ A lovely list of activities usually considered revolting are given air-time in the service of disarming shame. These include getting hair out of a shower drain, farting in enclosed spaces and enjoying the smell, and closely inspecting different bodily fluids. ‘Where there is no frankness, there is danger.’ Well, quite.

A diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder anchors the overarching ‘sense of impending doom’ – a clinical metric – that appears in many of Walker’s reflections, particularly around thresholds or boundary points (the West Gate Bridge looms large). Statistics appear and serve to showcase and place Walker’s struggle within a broader framework: one in ten Australians take anti-depressants daily, ‘one of the highest rates in the world’. A self-realisation is offered, one that she has ignored her entire life: ‘I’m scared, all the time. Of everything and nothing.’ The beep test of early years runs through the piece as metaphor: the quantification of frantic efforts in a capitalist society; the heart itself on the line.

The essay ‘Inside Out’ addresses self-harming behaviour and its potential psychological groundings. Walker tries it out ‘in my apartment in Prahran … to understand the appeal’. This upmarket exercise in experiential empathy foregrounds her place at the hospital frontline for her friend, where Walker is transfixed by the viscous flesh spilling out of its skin envelope. ‘I made her show me.’ The desire to see is unyielding. ‘I was almost disappointed when the ED doctor sewed it up.’ This essay sets out to test the relationships between agency and responsibility, and it documents the need to find alternative modes for self-definition. She chronicles research into self-harming behaviour that speaks to both sides of the equation: its risks, and the felt rewards for those who choose to open their skin. Her offerings are placed without judgement. For Walker, scars are ultimately development worksites, testaments to the healing and resilience of body and mind.

In her movements between the macro and micro of the subject matter, Walker holds the camera and turns the lens one final time. The essay ‘Contested Breath’ (first published in ABR in June–July 2020) closes the book and depicts the unexpected death of her mother against the backdrop of an unfolding pandemic. The strangeness that attends a loved one’s departure from life (digital residues; watching a body burn) places a poignant resolution on the collection’s overarching concern: our inability to control our bodies or the course of things, and the uneasy beauty of that final truth.

Comments powered by CComment