- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Alien of exceptional ability’

- Article Subtitle: Recalling Hazel Rowley ten years after her death

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The biographer Hazel Rowley enjoyed the fact that her green card – permitting her to work in America – classified her as an ‘Alien of exceptional ability’. This is close to perfect: her own biography in a few words. If not exactly an alien, she was usefully and often shrewdly awry in a variety of situations: in the academic world of the 1990s, in tense Parisian literary circles, and in the fraught environment of American race relations. It helped that she was Australian, and a relative outsider. The people she sought information from were less likely to categorise her and more inclined to talk. Her books – the major biographies of Christina Stead (1993) and Richard Wright (2001), Tête-à-tête: Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre (2005), and Franklin and Eleanor: An extraordinary marriage (2010) – are certainly evidence of exceptional ability, as well as obsession and tenacity.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

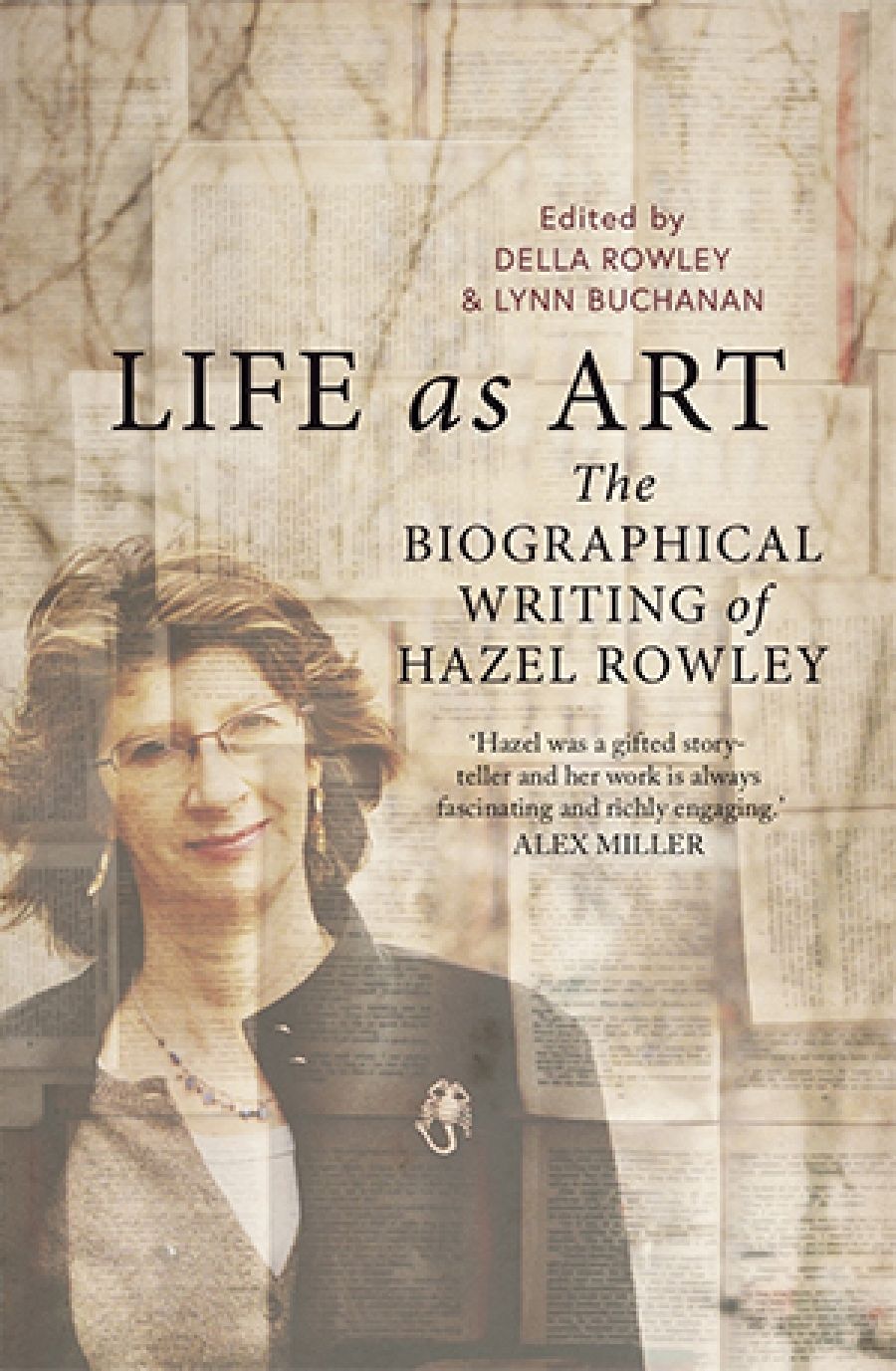

- Article Hero Image Caption: Hazel Rowley (image supplied)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Hazel Rowley (image supplied)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Brenda Walker reviews 'Life as Art: The biographical writing of Hazel Rowley' edited by Della Rowley and Lynn Buchanan

- Book 1 Title: Life as Art

- Book 1 Subtitle: The biographical writing of Hazel Rowley

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $34.99 pb, 255 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/LPn6RO

Rowley was scheduled to appear at the Perth Writers Festival in 2011. I had hoped to hear her speaking with Andrew O’Hagan, Rodney Hall, and Peter Rose. She died unexpectedly in New York a few days before she was due to appear. The news swept through the festival. It was difficult to believe. A poet read a tribute to her under the trees in a beautiful courtyard at the university where the festival was held. He seemed stunned, and so did the audience. Her books were exceptional, and there should have been so many more. Now, ten years after her death, her sister Della Rowley and her friend Lynn Buchanan have edited Life as Art: The biographical writing of Hazel Rowley. The book is warmly introduced by Drusilla Modjeska, who in the 1980s was a fellow ‘eager young feminist’ discussing with Rowley the prickliness of the famous older women they had (separately) interviewed: Beauvoir and Stead. Modjeska calls them ‘magisterial and perplexing’, but they didn’t entirely perplex Hazel. Modjeska questioned Stead about her decision to leave Australia when she was twenty-five. Stead was not much help, but Rowley’s biography gave Modjeska some understanding of this extreme move.

Life as Art has seven sections, all informatively introduced. The first two – ‘Writing Biography’ and ‘Research Trips and Personal Connections’ – contain essays, talks, and journal entries. Successive sections concern her subjects: Stead, Wright, Beauvoir and Sartre, and the Roosevelts. An afterword has journal entries sketching, in part, an idea for a new book about Brooklyn: ‘I love Stead’s idea that a city is an ocean of story. A light comes on in an apartment, and you know that there’s a story there. You open this or that door; from your subway window you see people in a passing train: there’s a story there.’ The final piece is an interview published in ABR just weeks before her death. She is asked what her favourite word is and she replies: ‘Courage.’ There are stories everywhere, but stories are not always straightforward and some take courage to investigate and to set down, as the section on Wright demonstrates. ‘I haven’t come here to live in white America: I want to live in real America,’ she writes, and the America that emerges from her work on Wright is devastating.

Rowley lived through a period of idealism and social agitation: ‘My generation came of age in the late 1960s and 1970s, a time of revolutionary change and hope.’ The disappointments came later, especially in the 1990s. Rowley dryly describes how she once pitied Beauvoir because she ‘had done so much to inspire the women’s movement and would not be alive to see what I took for granted my own generation would see: a complete transformation of society … and true equality between the sexes’. Beauvoir would have had to live a very long life to witness these things; furthermore, her own prestige had fluctuated. In 1980, when Deirdre Bair approached her publisher with a proposal to write a biography of Beauvoir, she was criticised for ‘request[ing] funding for an “over the hill French woman”’. Bair changed publishers and wrote a bestseller. A few decades after Bair’s unfortunate experience, HarperCollins, publisher of Tête-à-tête, was so accommodating that they brought out alternative versions in different countries to allow for variations in copyright legislation. (This is the kind of useful information that Life as Art provides.) Beauvoir is not above reproach, but it’s hard to imagine anyone being dismissive of her now; Modjeska calls her ‘one of the great pillars on which feminism stands’.

Rowley’s books are like highly finished canvases, and the great joy of Life as Art is the view it gives us of the underpainting. She had a clear idea of the value of biography at a time when literary criticism was uninterested in ‘the author’. Her respect for her subjects and her conviction that their lives supplied wider historical and personal insights carried her through the daunting period of research and writing. She calls her books ‘voyages, risky voyages, involving a great deal of passion on my part’. She internalises her work. Writing biographies has changed her, made her a ‘better person’: ‘The training you acquire as a biographer makes you far less interested in judging people; the challenge is to understand them.’ Her attitude is indispensable. Biographies can be particularly frustrating for the writer. People are often unreliable, they forget and they embellish; some are capricious. The subjects themselves – Stead in particular – are not easy to fathom. But the rewards are extraordinary. ‘I have stepped beyond the horizons of my own life,’ writes Rowley. She has taken us with her, in book after book.

In 1999, the biographer Claire Tomalin published Several Strangers, a collection of her reviews, prefaced by a frank autobiographical essay where she writes about the ‘several strangers who went by my name’. We are all sequential and plural, more than one person in the course of our lives. How wonderful it would have been to read Hazel Rowley’s books well into her old age, to follow all her changes. Life as Art reminds us of the measure of our loss.

Comments powered by CComment