- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘The world’s deadliest frontier’

- Article Subtitle: The callousness of the EU border regime

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Facing the ‘global refugee crisis’, politicians in Europe and Australia claim they are protecting their countries from the arrival of untold multitudes. Yet the ‘crisis’ is not global but highly specific. In 2019, seventy-six per cent of refugees came from just three countries (Congo, Myanmar, and Ukraine), while eighty-six per cent of refugees are hosted in a handful of countries in what is known as the Global South (especially Turkey, Jordan, Columbia, and Lebanon). Despite the significant contribution of Germany to hosting refugees, only ten per cent of the global refugee population live in Europe, comprising 0.6 per cent of the continent’s total population. There are 2,600,000 refugees in Europe today, compared with 11,000,000 at the end of World War II. The European Union’s challenges can scarcely be said to be at ‘crisis’ levels.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Where the Water Ends

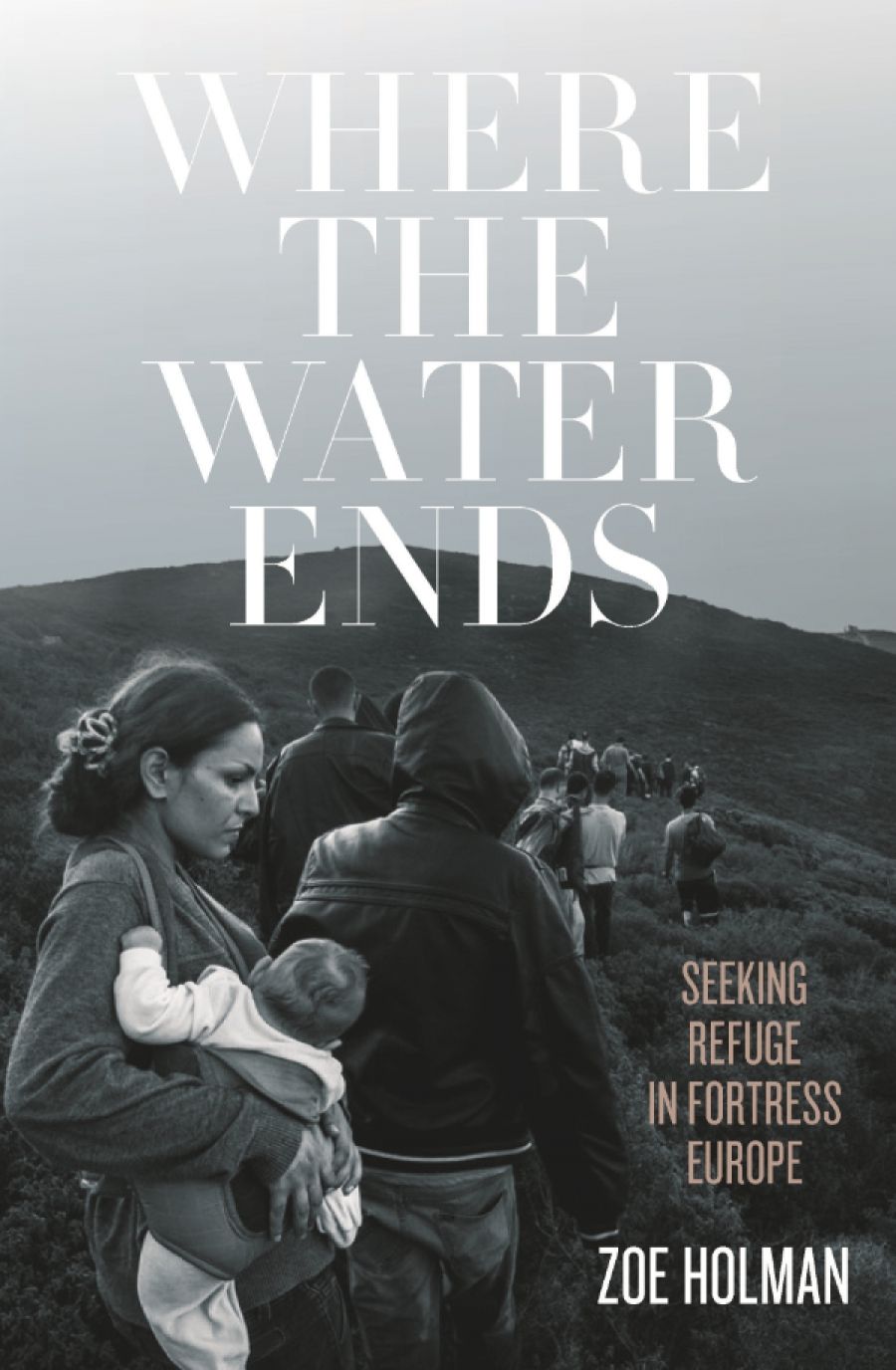

- Book 1 Title: Where the Water Ends

- Book 1 Subtitle: Seeking refuge in fortress Europe

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $29.99 pb, 319 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/RyyqMa

Even the word ‘refugee’, which was designed to provide basic rights to people who faced a ‘well-founded fear of persecution’ in the words of the 1951 Refugee Convention, is being redefined. In Europe, an unfounded fear of refugees has come to dominate politics and the politics of identity. Governments there have all too often learned from Australian ‘innovations’ in refugee deterrence and incarceration. For the refugees themselves, the two questions most often asked on arrival at Europe’s borders are: ‘Where are we?’ and ‘Are there guns?’

In Where the Water Ends, Zoe Holman, an accomplished journalist and poet with a PhD in Middle Eastern history, has written a remarkable book that traces the experience of refugees seeking passage to an increasingly fortified Europe. The European Union, she writes, has become the world’s deadliest frontier. Since the organisation was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012 for ‘the advancement of human rights’, more than 20,000 people have died or disappeared trying to reach its member states. Its border protection budget for 2021–27 is now €35 billion (about $54 billion). There are more fences and walls along its borders than was the case during the Cold War. This seems disproportionate to the actual scale of the ‘crisis’. In the words of one of Holman’s interviewees, if all those confined to camps in Greece were suddenly to be placed in an Athens suburb, ‘no one would notice’.

Where the Water Ends is a compelling account of life in the transit zone of asylum by those who are forced to live it. It documents the daily struggle of people fleeing war only to face a denied humanity on the borders of Europe in camps, prisons, or legal limbo as asylum claims are mired for years in ‘leaden bureaucracy’, and in the face of brutality from a militarised European border regime.

Just as remarkable as the stories themselves is Holman’s empathy. She travels along Europe’s borders staying in camps, visiting prisons, urban squats, and NGO-run centres. Fluent in Arabic, she focuses on the experiences of refugees from Middle Eastern countries where she has lived. In relating narratives of lived experience, Where the Water Ends builds not just a grim picture of the plight of refugees themselves but an unsparing picture of the EU’s political trajectory as a razor-wire curtain descends across a border region between East and West, which was, until recently, still one of cultural fluidity and exchange.

Katina, a Greek woman Holman meets, likes to show the Syrians her passport, which gives her birthplace as Aleppo. This was where she, along with thousands of Aegean islanders, fled to escape the Nazi occupation of Greece. Similarly, population exchanges between Greece and the newly established nation state of Turkey after World War I produced the apparent irony of Turkish-speaking Greeks and Greek-speaking Turks. Seeing the refugee boats arrive now in Greece is ‘like a mirror to the past’ recalls a turkosporoi who also faced stigmatisation on arrival in Greece. Elsewhere, Syrian refugees observe similarities in food, culture, language, architecture, and landscape. Certain moments in Athens are ‘Damascene’. Boundaries between East and West are never as clear as nationalists like to imagine. Throughout her journey, Holman unpicks this ‘confounding knot’:

these unexpected, embodied conjunctions of religion, language, citizenship, defying the ethno-nationalist prototypes we’ve been programmed to recognise. But really, it is simple: they are all just people from here. The other classifications – citizen, nation, Greek, Turk – came later. These are the falsifications, the anomalies.

Yet these are precisely the classifications, the search for a ‘clean nation’, that are being reinforced with EU funding. In defiance of international law, masked crews on unmarked vessels repel boats. Asylum seekers are stripped of possessions in Hungary, and beaten in Serbia. Amnesty International has protested about the Croatian border police tactic of breaking people’s legs to prevent them from returning. In Greece, refugees must run the gauntlet of ultra-right Golden Dawn supporters, many of whose leaders were put on trial for murder in 2015 in the biggest trial of fascists since Nuremberg.

The witnesses in Where the Water Ends tell of an endless transit between points of incarceration. ‘A transit situation is not only about a place or a length of time,’ observes Nasim in conversation with Holman. ‘It is much more about what you want and expect and cannot get. Transit is a status.’ When Moria refugee camp on Lesvos burned down, one activist observed that it is ‘not a tragedy but a policy, it is not an accident but a decision. Because Moria is an ideology.’

Part long-form journalism, part oral history, part politically engaged travel writing, Where the Water Ends is an outstanding achievement. The humanity of Zoe Holman’s work powerfully exposes the callousness of the EU border regime, whose ethno-nationalist trajectories have yet to run their course.

Comments powered by CComment