- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Australia’s nearest neighbour

- Article Subtitle: A beautifully illustrated book on New Guinea

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

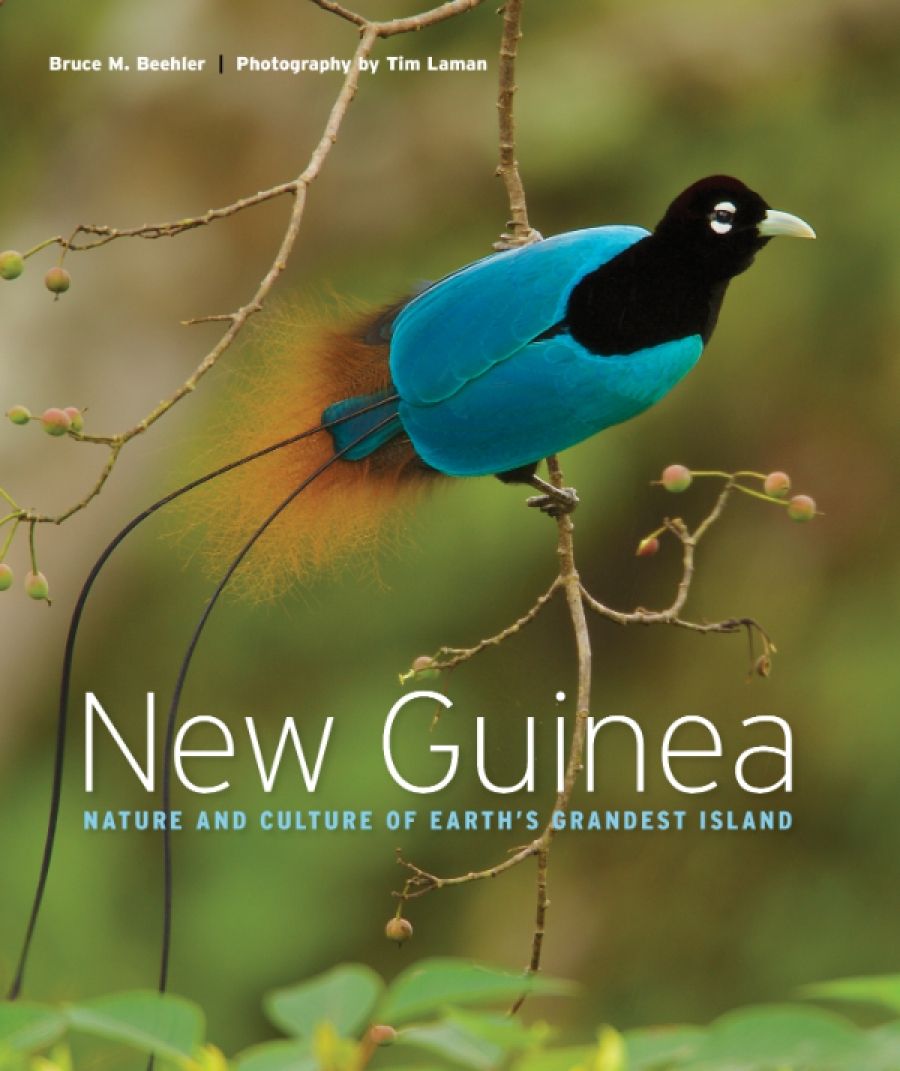

Australia’s nearest neighbour, the fabulous New Guinea, is one of the least developed and least known islands on earth. The largest and highest tropical island, it boasts extensive tracts of old-growth tropical forest (second only to the Amazon following massive destruction in Borneo and Sumatra), equatorial alpine environments, extensive lowland swamp forests, and huge abundances and diversities of orchids, rhododendrons, forest tree species, frogs, freshwater fish, and leeches. The fauna, exotic as well as diverse, include the richest radiations of tree kangaroos, echidnas, birds of paradise, and bowerbirds.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): New Guinea

- Book 1 Title: New Guinea

- Book 1 Subtitle: Nature and culture of Earth’s grandest island

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press, $49.99 hb, 376 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/5bbEr9

Human cultural diversity is equally remarkable with 1,100 documented language groups (twenty per cent of the world total). Biogeographical analyses indicate that the first human colonisers of New Guinea have histories of similar length to those of the First Nations peoples of Australia. Few other nations have such a high proportion of the population continuing to live traditional, self-sufficient, village lifestyles, based on shifting agriculture with staples of sweet potato and pigs in the highlands, and yams and fish in the lowlands. New Guinea is also likely to have been the site of domestication of bananas, sugarcane, taro, and yams.

New Guinea is also the richest island on Earth when it comes to mineral resources (notably gold, silver, and copper). These are being exploited by Western mining conglomerates with dubious long-term benefits to the indigenous people and, in some cases, massive environmental damage (e.g. the shameful Ok Tedi disaster, which caused biological degradation along 1,000 kilometres of the Ok Tedi and Fly rivers).

Australia has a long and intimate connection to New Guinea. Both ride on the Australian tectonic plate, and New Guinea has taken the brunt of the slow collision between the Australian and Pacific plates, throwing up the massive Central Cordillera mountain range and numerous younger and smaller, but nonetheless rugged, ranges to its north, including past and recent volcanism. During Pleistocene glacial periods, when sea levels were many tens of metres lower than today, New Guinea and Australia were joined for thousands of years by a broad plain across today’s Torres Strait, allowing considerable exchange of flora, fauna, and people. Thus, in a biogeographical sense, New Guinea is as much a part of Australia as is Tasmania.

A mother Huon Tree Kangaroo (Dendro lagus matschiel) and her young peer down from a mossy limb in mountain forest of the YUS Conservation Area of the Huon Peninsula of ENG, where this species is endemic. (Photo by Tim Laman. © Tim Laman 2020)

A mother Huon Tree Kangaroo (Dendro lagus matschiel) and her young peer down from a mossy limb in mountain forest of the YUS Conservation Area of the Huon Peninsula of ENG, where this species is endemic. (Photo by Tim Laman. © Tim Laman 2020)

The eastern half of New Guinea was an Australian External Territory from 1906 until 1975, when its independence was formalised by the Whitlam government, to become the nation Papua New Guinea. The western half is part of Indonesia (the provinces of Papua and West Papua), having been relinquished by the Dutch in 1962, under pressure from the Sukarno regime and via an agreement brokered by US diplomats. Between the two world wars, Australian kiaps (patrol officers) were prominent in the exploration by Westerners of the towering mountains of the Central Cordillera. A mere seventy to eighty years ago, they were among the first Westerners to encounter dense populations of highland people thriving in New Guinea’s interior upland valleys. The high human population densities in these upland valleys were made possible by the introduction of sweet potato and pigs, along with nitrogen-fixing Casuarina trees, centuries before the arrival of Westerners.

This beautifully illustrated book focuses on the natural and cultural values of the ‘grand island’. Bruce M. Beehler is an ornithologist who has devoted his life to documenting the birds of New Guinea, and his zoological and ecological expertise is evident throughout. Tim Laman is a skilled nature photographer, the only person to have photographed all thirty-nine species of bird of paradise in the wild. Together, they form the perfect team to produce this book.

I cannot think of a similar compilation that brings together so brilliantly and thoroughly the natural and human history of any region. Chapters cover geology, climate, terrestrial and marine flora and fauna, human history, modern human culture (including village life), and a concise summary of the many looming ecological threats such as industrial-scale logging and palm oil monocultures. Throughout, Laman’s photographs of environments, plants, animals, and people bring to life Beehler’s concise and precise sentences. All chapters are approached from the viewpoint of an evolutionary ecologist, resulting in a text that weaves the biogeographical and cultural threads into a very satisfying whole. The impacts of geological processes, notably plate tectonics, on topography and climate are made clear, as are the consequential effects on the diversity and distribution of flora and fauna, and on human culture and economics. For example, in many districts the brutal and unstable topography and massive rainfall combine to make prohibitive the costs of building and maintaining roads and bridges, limiting cultural integration and economic development.

Beehler’s writing is mostly detached and factual, but he makes an exception for what he terms cultural conservation. He laments the loss of cultural knowledge and traditions as thousands of ancient knowledge systems and cosmologies were actively dismantled by Christian missionaries during the twentieth century. He describes this process as a tragedy and a crime against traditional humankind, one that led to degradation and squalor in the lives of many. However, other serious social problems that are evident even in traditional village communities are glossed over. These include shocking gender inequality, poverty, the heavy hand of the Indonesian military in the west, and lawlessness in provincial towns and along highways in the east. The latter impedes development of a nature-based tourism industry, potentially a major source of sustainable income for local communities within this remarkable region that has so much to offer ecotourists. Ecuador and Botswana offer fine examples of how this can be achieved.

Given our shared history, shared cultural and natural values, and the fact that Australia’s Exclusive Economic Zone extends to within a few kilometres of the coast of Papua New Guinea, surely Australia should be more actively assisting the sustainable development of both Papua New Guinea and Indonesian New Guinea? Recent reports of Chinese plans to build a major port on Daru Island in the Torres Strait, a handful of kilometres from Australia’s EEZ, highlight Australia’s recent neglect of our nearest neighbour with its fabulous natural and cultural values that are brought to life in this beautifully crafted book. The recommended retail price offers remarkable value.

Comments powered by CComment