- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Science and Technology

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Haunted history

- Article Subtitle: The BAAS’s 84th congress

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Founded in 1831, the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) sought to redress impediments to scientific progress that arose in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, determining that the BAAS would ‘give a stronger impulse and more systematic direction to scientific inquiry … [and] promote the intercourse of cultivators of science’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): A Trip to the Dominions

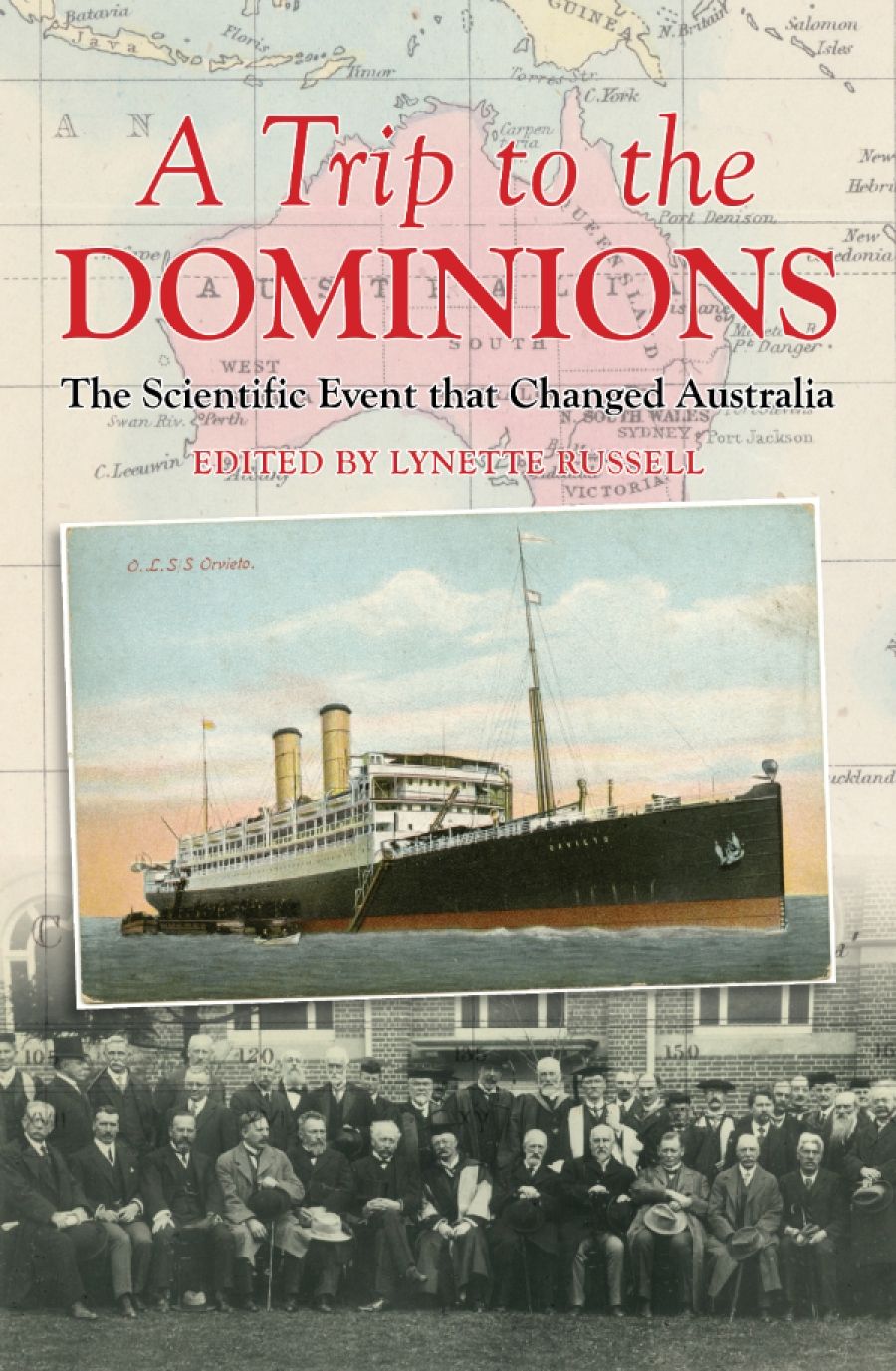

- Book 1 Title: A Trip to the Dominions

- Book 1 Subtitle: The scientific event that changed Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $29.95 pb, 160 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/YggPem

Not quite a hundred years later, on the eve of World War I, several hundred scientists travelled to Australia to attend the BAAS’s 84th congress, an expedition funded by the Australian government at a cost (in today’s money) of several million dollars. The delegates ventured across the continent ‘[engaging] with Antipodean physical and social scientists, industry, cultural institutions, and Indigenous cultures’. A significant facet of this engagement was a ‘serious consideration [of] both Aboriginal history and the place of Aboriginal people in the colonial present’.

A Trip to the Dominions, a collection of five papers originally workshopped at London’s Royal Anthropological Institution in 2014, focuses on the congress’s contribution to the flourishing of Australian anthropological studies and a consequential shift in perceptions of Aboriginal culture.

Lynette Russell, an anthropological historian at Monash University, provides an overview of the congress, offering striking details not only of its agenda but also of the logistics involved. For example, three ships were requisitioned to transport 155 scientists from Europe to Australia (two of which were commandeered as naval troop ships soon after the scientists’ arrival, complicating their return journey). The outbreak of war curtailed the itinerary of the congress and led to a handful of scientists being briefly detained as enemy aliens. But to judge by the crowds that came to the open sessions – 2,000 people attended in Melbourne – and by the response of newspapers, which printed entire lectures in broadsheet supplements, the venture overall was a tremendous success.

Christopher Morton, Head of Curatorial, Research and Teaching at Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum, augments our understanding of the quotidian characteristics of the congress with his evaluation of the diary kept by archaeologist Henry Balfour. Put together in ‘the manner of a holiday scrapbook’ and extending to three volumes, the diary collates menus, tickets, political cartoons, and sketches with entries recording encounters with Aboriginal Australians: ‘Saw some boomerang throwing … After lunch the natives gave a corrobborrie [sic] dance … The dancers were painted in white stripes.’

Scientists journeyed to an Aboriginal mission in Western Australia ‘where they met, observed, recorded and measured the mission inmates’ and made plaster head-casts of Aboriginal men, women, and children, marvelling at the ‘perfect freedom’ of those Indigenous peoples who were living under the care of the state.

State reception in the grounds of the University of Queensland for visiting members of the BAAS, Brisbane, 31 August 1914 (The Queenslander, September 5, 1914, p. 24).

State reception in the grounds of the University of Queensland for visiting members of the BAAS, Brisbane, 31 August 1914 (The Queenslander, September 5, 1914, p. 24).

Russell stresses that the congress occurred at a time when, due to the White Australia policy, Indigenous Australians were largely invisible to the majority of the population: ‘[i]n a mere 80 years, the streets of Melbourne had largely been vacated of an Aboriginal presence … [and] traditional ways of life … had been irrevocably disrupted’.

The prevailing view was that Aboriginal culture had ‘changed little over the ages’, and Indigenous occupation of the continent was regarded as ‘relatively shallow’. In this context, a lecture arguing that the ‘“Talgai skull” … the oldest human skull to have been found in Australia … pointed to a deep history of Aboriginal presence in Australia’ was of particular note, the finding being ‘the first step in establishing the antiquity of Australia’s Indigenous peoples and hence their claims to a long occupation of the continent’.

Assessments of Aboriginal Australians in this period were dominated by the theory of salvage anthropology, which advocated for the cataloguing of the traditional knowledge and culture of peoples who were ‘deemed to be rapidly coming extinct’, a paradigm which included no imperative to ‘stem [the] impacts’ of the colonisation threatening Indigenous populations worldwide.

As Ian McNiven, Head of Indigenous Archaeology at Monash University, demonstrates in his appraisal of Alfred and Kathleen Haddon’s fieldwork among Torres Strait Islander peoples, studies embracing salvage anthropology were wont to misread the evolving nature of Aboriginal culture and its capacity to adapt to the ravages brought by colonial expansion. The Haddons’ documentation of their work (some of which is reproduced in an appendix) nevertheless furnished evidence of ‘cultural continuities between past and present’ subsequently used to support native title judgments.

In a diffuse argument that takes in au pair Elsie Masson’s memoir about working in the Northern Territory (published in 1915 as An Untamed Territory) and anthropologist Walter Baldwin Spencer’s administrative role overseeing Aboriginal Australians, University of Western Australia historian Jane Lydon investigates the relationship between governance, particularly policies of assimilation and control, and ‘modes of knowing’ that depict Indigenous peoples as ‘preserving an early stage of human development’.

Leigh Boucher, a historian at Macquarie University, also examines the relationship between knowledge and power in the provision of ‘colonial management’, cogently tracing connections between the influential field guide Notes and Queries on Anthropology and an objectification and infantilisation of Indigenous Australians that marked them as ‘incapable of surviving settler modernity without … protection’.

Written predominantly for a specialist audience, A Trip to the Dominions is nevertheless accessible to a general readership. It encompasses stories of our past that demand to be disseminated beyond the bounds of academia.

With respect to his own country’s encounter with imperialism, Michael D. Higgins, president of Ireland, recently wrote that it is only by both remembering and understanding our past that ‘we can facilitate a more authentic interpretation not only of our shared history, but also [of the] possibilities for the future’.

In her account of the BAAS itinerary, Lynette Russell comments regarding an excursion to the Coranderrk Aboriginal reserve that ‘[t]he response of the Kulin people housed at Coranderrk is unrecorded’. These undocumented Indigenous voices haunt A Trip to the Dominions, just as they haunt our own history. The swell of First Nations writers and artists beginning to fill this void is a vital step in the realisation of our own more authentic narrative.

Comments powered by CComment