- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Common ground

- Article Subtitle: A hybridised exploration of distance

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

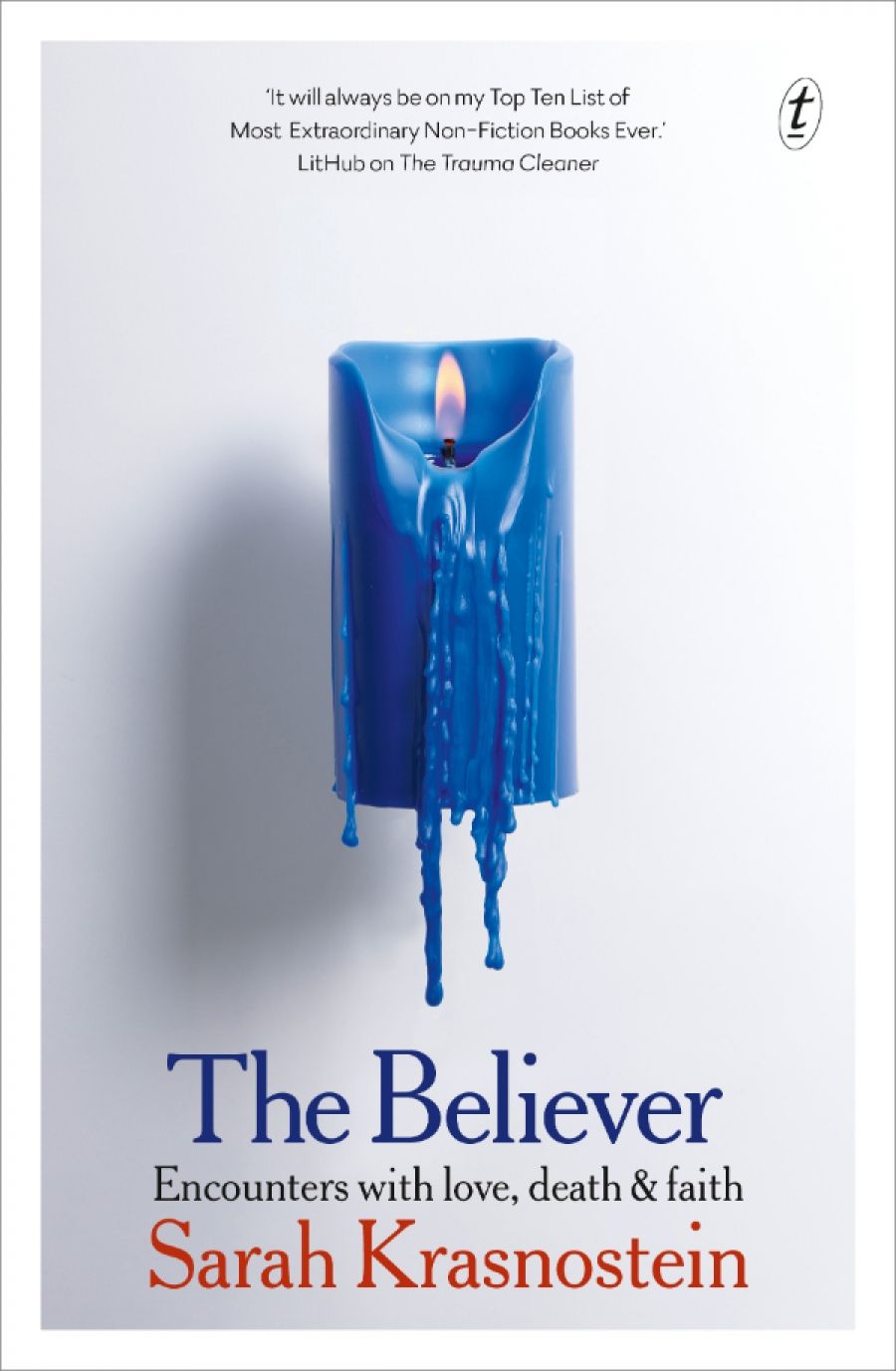

Subtitled ‘Encounters with love, death and faith’, Sarah Krasnostein’s The Believer takes on big themes. In this work of creative non-fiction that combines memoir, journalism, and philosophical inquiry, Krasnostein details her meetings with people whose beliefs she finds unfathomable but whom she is driven to understand. Her own guiding faith on this journey is that ‘we are united in the emotions that drive us into the beliefs that separate us’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): The Believer

- Book 1 Title: The Believer

- Book 1 Subtitle: Encounters with love, death and faith

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $34.99 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/P00EDN

Fans of Krasnostein’s first book, The Trauma Cleaner (2017), will find much to admire in her second: her curiosity, her even hand, her focus not on people’s coherence but on their contradictions, her lateral thinking. Krasnostein’s two books are also, in essential ways, opposites – or perhaps counterparts. The Trauma Cleaner uses many questions to explore one person’s story. The Believer uses many people’s stories to explore one question. The Believer is, in that sense, a thesis. It asks the following question: how do we deal with the distance between the world as it is, and the world as we’d like it to be?

The work is divided into two parts, each comprising three intertwined narratives. ‘Part 1: Below’ follows a death doula, a group of paranormal investigators, and the team behind a creationist museum in Kentucky. ‘Part 2: Above’ features a woman incarcerated for the murder of her abuser, a range of ufologists, and members of a New York City community of Mennonites. The two parts are bookended by a prologue and a coda, the former establishing Krasnostein’s narrative ‘I’ and setting out the book’s framework as a study of distance. Krasnostein is especially interested in psychological distance – the cognitive separation between ourselves and other people, events, or times – which she describes as ‘our superpower and our Achilles heel, a way of flying or falling’.

Examining the human need to ‘fabricate bespoke delusions’ to avoid grief, Krasnostein is interested in how we lean into or away from discomfort. For the Creation Museum staff, ‘the heart’s refusal to accept the world as it is’ breeds an emphasis on answers over questions and certainty over accuracy. For the death doula, it’s the opposite: she has spent decades practising ‘the counter-intuitive art of moving towards the things that scared her so they became known’. Then there are the ghost-hunters and ufologists, within whose ranks one finds examples of both cautious open-mindedness and megalomania.

As a study in common ground sought at the furthest reaches, the narrator’s distance from her interviewees varies. Krasnostein approaches each encounter with openness, and humanises interviewees by describing their backgrounds, families, and mannerisms. Nonetheless, when speaking with those who believe in ‘the particular flavour of logic promoted at the Creation Museum’ or who claim that transgender people ‘need to be taken to truth’, her sense is that she ‘cannot say that we inhabit a mutually recognisable world’. Here, despite affection, distance remains: ‘Because they believe I am going to Hell and I believe they may already be living in one.’

The most gratifying narratives are, perhaps predictably, those where the distance is shortest. The warmth of Krasnostein’s encounters with Annie, who guides others through grief, and with Lynn, who survived decades in jail with grace, is reminiscent of Krasnostein’s superb first book. In these narratives, which are individual rather than collective, she is at her most penetrating. This confirms Krasnostein’s observation that ‘to bridge the distance between us, we must get closer, first of all, with ourselves.’

While Krasnostein’s identification as a ‘secular humanist Jewish [woman]’ is discussed only occasionally, it is never far from the surface in her work’s philosophical undercurrents. The scholarship of Hannah Arendt and Martin Buber is often cited. Krasnostein’s legacy as a descendant of Holocaust survivors means that avoiding the question of meaningless suffering was never an option. To the narrator, ‘the real ghosts’ of her childhood are not cranky poltergeists; they are the gaps in her family tree.

The personal component of Krasnostein’s narrative is deeply moving. At times I found myself wishing, in the book’s second half, for more of the ‘Sarah’ of its first half. What does it mean for Krasnostein, I wondered, to speak with people who, while perfectly hospitable, commend to her the lectures of anti-Semitic alien conspiracy theorists? Is she ever tempted to close (or slam) the door on conversations where common ground feels eclipsed by the harm of the views held? This is a perennial problem most people will be familiar with, more relevant than ever in the era of misinformation, clickbait journalism, and social media platforms that reward intemperance and monetise division. Krasnostein, in a restrained approach reminiscent of Chloe Hooper’s journalism, lets her interviewees’ beliefs speak for themselves.

A highlight of The Believer is Krasnostein’s imagery. Questions and answers in a church discussion are like ‘an awkward high-five, they never quite match up’. A husband and wife on a sofa ‘lean towards each other like a pair of old boots’. In one hilarious description from an otherwise perturbing scene, the narrator strokes a ‘hairless cat, Lilith, who feels under hand like an enormous dried apricot’. Krasnostein’s narrative voice – a blend of insight, authenticity, and journalistic skill – is like a slow-cooked Shabbat cholent, rich and wholesome, every flavour running into the other.

The question that echoes beyond the pages is, ‘Could the key to seeing clearly ... lie less in calling each other out on our magical thinking, and more in focusing on why we are all compelled to do it from time to time?’ But Krasnostein loves contradictions. Concluding her prologue, she writes, ‘One of the lies writers tell themselves is that all things should be understood.’ The implications of this line’s inclusion in a work that attempts to understand distant others are worth contemplating.

Comments powered by CComment