- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The pain-eater

- Article Subtitle: The enigmatic life of a loser

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Have you ever noticed how boxing matches invariably deflate into two breathless people hugging each other? In pugilistic parlance, this is called a clinch. It is a defensive tactic, a way for fighters besieged by their opponent’s assault to create a pause and regain their equilibrium. And while it is beyond cliché for books to be hailed as knockouts or haymakers or other emptied expressions of victory, Michael Winkler’s Grimmish is the best literary clinch you’ll ever read. It is the honest account of a writer overmatched by his subject matter and left clinging on for dear life.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

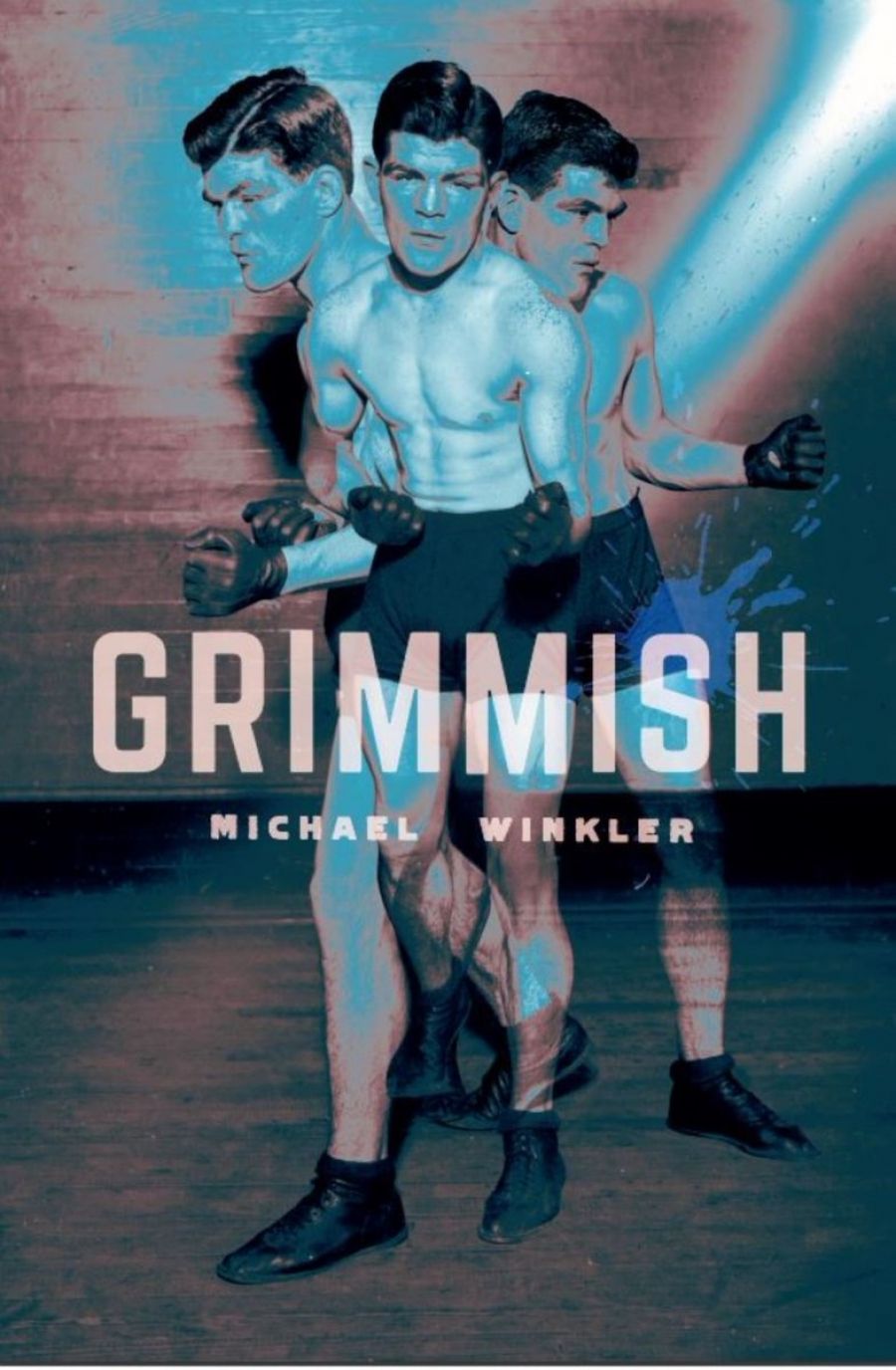

- Book 1 Title: Grimmish

- Book 1 Biblio: Westbourne Books, $27.99 pb, 213 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/x99aGR

On the surface, Grimmish is the biography of one Joe Grim, an Italian who escaped poverty in Avellino for Philadelphia and the professional boxing circuit at the turn of the twentieth century. Grim transcended an unspectacular win–loss record through his unique ability to endure massive amounts of physical punishment and remain standing. As word of this curious ‘pain-eater’ spread, Grim became ‘a spectacle rather than a fighter’, one who nonetheless managed to eke out a moderately lucrative career. He fought some of that era’s luminaries, including Jack Johnson, the first African American heavyweight champion. After pummelling Grim for six rounds and seventeen knockdowns in 1905, only to watch him flicker back to life like a trick candle, Johnson declared, ‘I just don’t believe that man is made of flesh and blood.’

After introducing Grim and his bizarre talent, Winkler zooms in on the boxer’s 1908–9 tour of Australia. For a year and a half, Grim crossed the continent flagellating himself on the gloves of second-rate scrappers such as George ‘Cobar Chicken’ Stirling, before being temporarily institutionalised in a Claremont asylum. The cause of Grim’s fragile mental health is blindingly obvious – try being the heavyweight circuit’s stress ball and see how your cognition trucks along – but the details of his stay are murky. This is because Winkler has only an admission slip and a few newspaper snippets with which to recreate such a pivotal moment in his subject’s life. When the research well dries up, Winkler is left lamenting the ‘many parts of Grim’s Australian adventure that are undocumented and must remain unknown’.

To better spelunk these submerged facets of Grim’s past, Winkler turns to fiction, sprinkling the book with short stories about Grim that vary widely in tone and perspective but that are equally compelling. The descriptions of Grim’s matches are enlivened by Winkler channelling the fruity sports-journo language of the era, with a boxer’s eyes ‘like raisins pushed deep into dough’ and punches landing like ‘a shovel hitting a watermelon’. There are also quieter moments in which we get a sense of how denuded rural Australia would have seemed to an Italian Catholic, such as when Grim endures ‘a dry husk of a church service. Not much ritual, no Latin, no magic.’ Elsewhere, Grim recedes into the background as scenes of terrible violence gush around him, most unforgettably during a pub headbutting competition that leaves its participants ‘maroon and puce, livid with battery’. Even when these stories check realism at the door – one involves the torture of a talking goat – their ruminations on pain connect them back to the real-life Grim.

Maggie O’Farrell recently used this mix of fact and forced invention to transform a haiku’s worth of information on Shakespeare’s son, Hamnet, into a sumptuously detailed novel of the same name. For writers like O’Farrell, or Australia’s Hannah Kent, the trick is to blend the known and unknown into one undifferentiated puree. Winkler’s approach could not be more different. He routinely breaks the fourth wall to remind us of his fraud, shouting ‘how pale is this simulacrum? How faint the whisper?’ This metacommentary includes a three-page book review of Grimmish that lashes its own writer for his ‘deliberately rickety storytelling structures’ and ‘the stunt of toppling his mouthpieces into knowingly unrealistic dialogue’. Winkler’s despair at failing Grim metastasises into professional regret: ‘I have spent my allotted years in a room alone writing words no-one wants or will ever read.’

Winkler is an excellent critic – his good work features regularly in these pages – so it’s shocking how off-target the self-assessment is here. His 2016 Calibre Prize-winning essay, ‘The Great Red Whale’, also featured an anxious voice wringing its hands over passages of otherwise imperial prose. What’s Winkler’s deal? Does he enjoy playing rope-a-dope, pretending that he can barely string a sentence together before bowling us over with another sparkling insight? Perhaps. Or maybe these two brilliant texts are linked by their inability to convey a sensation that has been Winkler’s constant partner: pain. Throughout Grimmish, Winkler opens up about his struggles with depression: ‘I ache until my eyeballs sweat.’ As a result, he admits to being ‘engrossed by the idea of powerful forbearance’. In one scene, Grim contemplates a crucifix, wondering if he could have endured the torture as Christ did; it is easy to imagine Winkler looking at a photo of bloodied-nose Grim and wondering the same. The problem, as Winkler astutely notes, is that the specifics of pain are difficult to conceive, at least until you are the one hurting: ‘it makes no sound, has no colour or smell, occupies no physical space. And yet at its most extreme, pain becomes the only thing of which the sufferer is aware.’

Winkler never does figure out exactly how Grim tolerated ‘exchanging pain for a living wage’. In doggedly dissecting this failure, however, he comes to recognise himself as a sort of kinsman to his hero: ‘Could my unfulfilled writing career, replete with self-sabotage and propensity for mock-heroic failure, be my own version of Grim’s pain pantomime?’ The next time writing punches Winkler in the face, I’ll buy a ticket.

Comments powered by CComment