- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Publishing

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Objects of readerly desire’

- Article Subtitle: A close look at Australia's consequential book editors

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Craig Munro’s latest book shines a spotlight on the work of some very different Australian book editors. It begins in the 1890s, when A.G. Stephens came into prominence as literary editor of The Bulletin’s famous Red Page. It continues through the trials and tribulations of P.R. (‘Inky’) Stephensen in publishing and radical politics in the interwar period and his internment during the war for his association with the Australia First Movement. Literary Lion Tamers then moves on to Beatrice Davis’s long career as a professional book editor with Angus & Robertson after World War II. It concludes with Rosanne Fitzgibbon, with whom Munro developed fiction and poetry lists at the University of Queensland Press.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

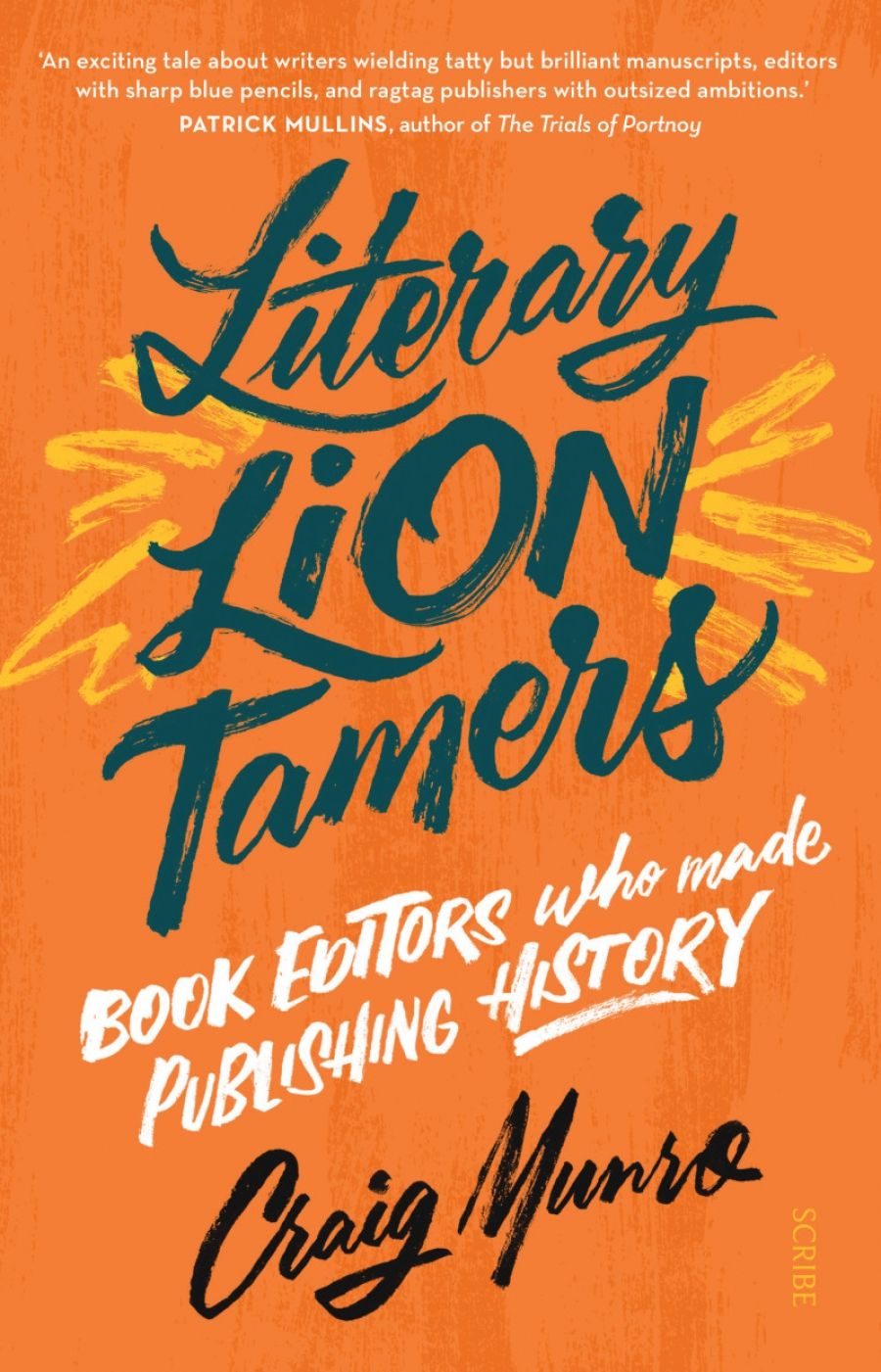

- Book 1 Title: Literary Lion Tamers

- Book 1 Subtitle: Book editors who made publishing history

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $29.99 pb, 274 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/3PPWNk

These literary editors are lion tamers in the sense that they took on some of the most unlikely manuscripts and turned them into gargantuan novels of unprecedented and inimitable style: Joseph Furphy’s Such Is Life (1903), tamed by A.G. Stephens; Xavier Herbert’s Capricornia (1938), whipped into shape by Inky Stephensen, and Eve Langley’s The Pea-Pickers (1942), rescued by Beatrice Davis. They did not so much tame their authors as train them to jump through the hoops necessary to bring the works of their wild imaginations into the public world of books. For instance, Furphy was asked to provide or pay for two typed copies of his 1,125 handwritten pages. Hard up as he was, he bought his own typewriter and spent the best part of a year laboriously typing it out himself in his backyard shed in Shepparton.

Both Stephens and Stephensen had not only to edit massive manuscripts but also to drum up a publisher. Neither of them went to Angus & Robertson, which was about the only local book publisher worthy of the name in those days. Furphy’s Such Is Life was eventually published by the Bulletin Company, and Herbert’s Capricornia by a later Sydney journal, The Publicist, where Stephensen was employed. This mouthpiece of the pro-fascist Australia First Movement was owned by W.J. Miles, father of the famous Bea Miles, the prototype of Kate Grenville’s character Lilian in her novels Lilian’s Story (1985) and Dark Places (1994).

Literary Lion Tamers is an entertaining story that picks up on dozens of additional dramatis personae on its way through the careers of these editors. There are other authors: Shaw Neilson and Steele Rudd were among Stephens’s notable discoveries; Stephensen edited and ghostwrote books for Frank Clune for many years; Davis took on a stormy relationship with Herbert when she took on his second novel, Soldiers’ Women (1961), and befriended another eccentric writer, Ernestine Hill, as well as maintaining more conventional editorial relationships with literary novelists such as Thea Astley. And there are various other characters, ranging from J.F. Archibald and Henry Lawson, through Norman Lindsay and his son Jack, to Stephensen’s publishing adventures in London with two literary mavericks of the 1920s, D.H. Lawrence (reviled for his Lady Chatterley’s Lover) and Aleister Crowley (the notorious satanist).

Davis’s long reign as the doyenne of literary publishing culminates in the drama of takeovers that led to her moving to Nelson in 1973, taking her most prized writers with her. Closer to the present day, Fitzgibbon’s work with the likes of Peter Carey, Olga Masters, and Gillian Mears seems smooth sailing in comparison to the wild old days of Sydney publishing. As the first recipient of the Beatrice Davis Fellowship, an editorial residency in New York, Fitzgibbon (who died in 2012) occupies an important place in Munro’s story as an inheritor of the Davis tradition, as well as a representative of the many fine women editors who came to dominate literary publishing in Australia.

In concluding his story, Munro eloquently describes the work of editors as ‘transforming raw manuscripts into objects of readerly desire’. At times I wanted to know more about what such an editorial transformation involved. Take the case of Furphy’s Such Is Life. When the first-time author sent his vast manuscript to The Bulletin, requesting publishing advice, Stephens replied that the book was fit to be an Australian classic and offered Furphy detailed information about the practicalities of book publishing, asking whether he would share the financial risk of publication. In response to this, it seems, Furphy invited Stephens to reread the manuscript, ‘ruthlessly drawing your blue pencil across every sentence, paragraph or page which offends your literary judgement’ – an open invitation, if ever there was one! We then learn that the book was finally published in 1903, six years after it first arrived on Stephens’s desk, with emendations so significant that recent Furphy scholars (quoted by Munro) judge that it changed the novel’s centre of gravity and subdued its language (as well as introducing errors). How frustrating if, like me, you are not a Furphy scholar and know only that Furphy himself removed two long chapters, which were later published posthumously in book form as Rigby’s Romance (1921) and The Buln-Buln and the Brolga (1948). What was Stephens’s editorial advice to the author of this anticipated classic? What exactly did this literary lion tamer do with his blue pencil? How did Furphy feel about it?

Literary Lion Tamers offers an unusual perspective on the Australian novel as seen through the lens of book publishing history. This is a topic about which Craig Munro is vastly knowledgeable, having co-edited (with Robyn Sheahan-Bright) Paper Empires: A history of the book in Australia 1946–2005 (2006) and published a history of UQP, as well as, more recently, a memoir of his own career as editor and publisher there (Under Cover: Adventures in the art of editing [2015]).

Munro has also written a biography of Inky Stephensen, a figure of fascination for him since the 1970s, when his own encounter with Xavier Herbert and the manuscript of Poor Fellow My Country led him back to the man who had brought Capricornia into print. The young Munro had hoped to edit the latter book for publication, but the irascible author responded to his critical suggestions by taking his book to another publisher. This anecdote is typical of the way Munro has woven his stories together: his personal connection to the stories of his ‘lion tamers’, and sometimes to their authors as well, brings the book closer to the mode of memoir than to history-writing. It’s a most engaging read, bound to send you back to the biographies of these editors, as well as to the massive Australian novels and other works they brought to print.

Comments powered by CComment