- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Life as a sliced loaf

- Article Subtitle: George Saunders’s masterclass in short-story writing

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘I consider myself more a vaudevillean than a scholar,’ George Saunders writes cheekily in his introduction to this collection. Yes, he is indeed a professor of creative writing at Syracuse University in upstate New York, a Booker Prize-winning novelist, and a regular in the pages of the New Yorker, but in A Swim in a Pond in the Rain he is first and foremost a vaudevillean: in seven short acts he sings, dances, and acts the comedian. According to Martin Amis, ‘all writers who are any good are funny’, even Kafka and Tolstoy, and he has a point. Saunders may not be quite vicious enough to qualify as ‘any good’ in Amis’s terms, but he is at least unfailingly sharp and good-humoured.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: George Saunders (Agence Opale/Alamy)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): George Saunders

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

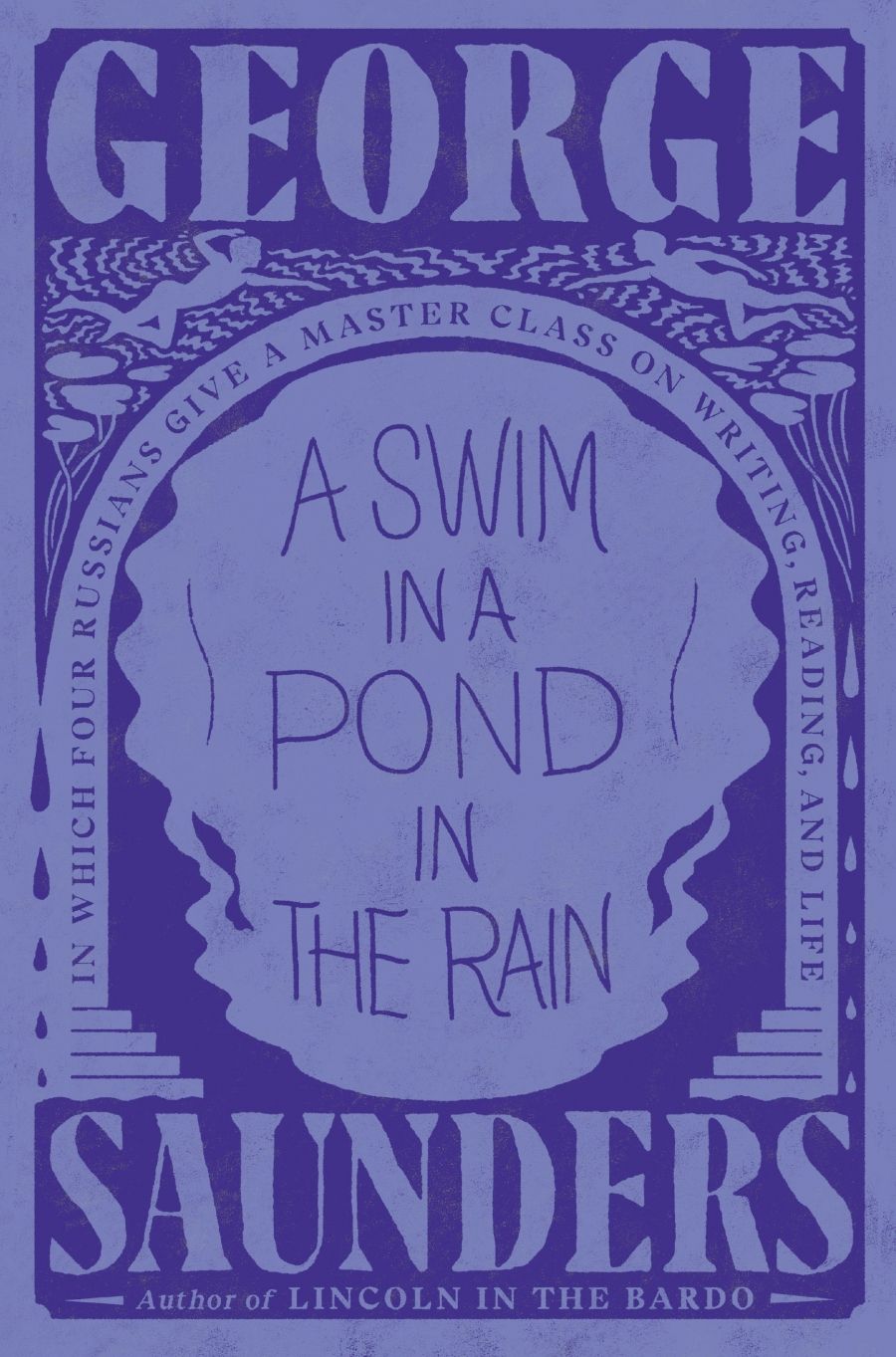

- Book 1 Title: A Swim in a Pond in the Rain

- Book 1 Subtitle: In which four dead Russians give us a masterclass in writing and life

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $34.99 pb, 422 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/LPPBLo

Each of these seven acts is a masterclass in short-story writing based on a famous Russian short story from ‘the high-water period of the form’ (1830s to the early twentieth century). It’s an outstanding performance, if not quite a dazzling one – after all, he’s not Nabokov and he knows no Russian (and it shows). Nor is it a flashy one à la Amis, who works the crowd on the very subject of short fiction in Inside Story (2020). (Life, says Amis, is not a novel but a ‘sliced loaf of short stories’.) Yet it’s much more than a simply entertaining performance: every sentence is enlivening. The patter can sometimes be irritating (his American conviction that deep down everyone will want what he wants from a story, not to mention the odd ‘jeez’, ‘fuck’, ‘dang’, and use of ‘per’ to mean ‘in the opinion of’). However, Saunders usually irritates in a productive, oysterish sort of way: something inside you starts to sparkle as you engage with him.

These classes are frequently illuminating as well, not so much about Gogol, Tolstoy, Turgenev, and Chekhov, about whom he has little to say that’s new and quite a lot that’s daffy, but about how the best short fiction is made and why it’s the best. (Cocking a refreshing snook at fashionable taboos, Saunders has no more problem with ideas such as ‘best’ than he does with arguing about a writer’s intentions.)

Saunders disarmingly believes in ‘universal laws of fiction’. In accordance with these laws, a good short story is ‘ruthlessly efficient’ (every syllable advances the story entertainingly), details are specific (the cat in the window is white and asleep, not just a cat), and, crucially, energy is created at the beginning of the story and is transferred, with escalating dynamism, into a different, unexpected kind of energy at the end, ‘like a bucket of water headed for a fire’. It’s the escalation that keeps you turning the pages. As Saunders remarks, the most urgent question for any writer is what makes her reader keep reading (Saunders always uses the feminine pronoun as the default third-person singular pronoun), eager for the final transfer of energy. This is all bracing stuff.

For example, alone and miserable on a fine spring morning, Marya in Chekhov’s story ‘In the Cart’ is ripe for transformation. We have character, we have the bucket of water, we expect story. Then a happy, unmarried landowner joins her on the road. Is he the fire that will need to be put out? (No, but we read on, agog.)

In ‘Alyosha the Pot’, Tolstoy gives Alyosha (a ‘stick figure’, as Saunders notes) the defining attribute of cheerful obedience. This will need to be put to the test. When he falls off a roof and lies dying, it is. Cheerful obedience is transformed into another, spiritual kind of energy – unconvincingly from Saunders’ point of view. His political views are close to Tolstoy’s in one regard: the edifice of comfortable living rests on a foundation of human misery (‘the behemoth of capitalism’, with its ‘malformed detritus’ of suffering people), but he is no Tolstoyan in his views on what to do about it. He cannot accept the conclusion he believes Tolstoy wants him to reach at the end of ‘Alyosha the Pot’: that Alyosha was right to live and die without complaint.

Saunders’ text is peppered with little interrogatory coups de foudre, forcing the reader to ask herself a few Big Questions. Why do we read? Why do we write? Is fiction a moral-ethical tool (as Saunders believes the Russians saw it)? What were we ‘put here’ to accomplish? But ‘the million-dollar question’ is: what makes a reader keep reading? What do we care about? Unless you can come up with some sort of answer to it, there’s no point in your writing.

When it’s put to Bill Buford, fiction editor at the New Yorker, he’s quoted as saying: ‘Well, I read a line. And I like it … enough to read the next.’ That’s pithy, but Saunders actually has much more interesting answers to the question. For instance, he suggests that fiction is ‘the most effective mind-to-mind communication ever devised’. Taken literally, this is deliciously provocative. Might it also be true?

These essays are not scholarly readings of seven Russian stories, but are meant to help us read and write better. Many of Saunders’ insights are inspiring. I would argue, however, that his reading of Gogol in particular is seriously wide of the mark. He seems to want ‘The Nose’ (of all things) to ‘add up’. Gogol’s writing is absurd, grotesque, surreal, an iteration of the Ukrainian folk-tale – it does not ‘add up’. Gogol cannot be ‘improved’, either, as Saunders avers, by being made less sexist, clumsy, or ‘graceless’. He will just be made more 2021 upstate New York. Gogol does not imply that ‘miscommunication is … at the heart of all human suffering’, as Saunders would like him to. In ‘The Nose’, Kovalyov’s nose, which vanishes inexplicably from his face to reappear in a barber’s breakfast bun, does not represent his ‘wild inner spirit’ (since he doesn’t have one), but, on the contrary, his obsession with social status. Detached from his face, his nose has a rank Kovalyov can only dream of.

Saunders’ own dream is of a world where ‘there’s a vast underground network for goodness at work in the world’, ‘assholes’ are not allowed to remain assholes (as they are in Tolstoy’s stories), and writers can be taught to find ‘the place from which they will write the stories only they could write, using what makes them uniquely themselves’. He dreams of a world in which any sign of ‘sexist, racist, homophobic, transphobic, pedantic, appropriative, derivative’ attitudes and other moral failings in a story can be eliminated, making it ‘(always) become a better story’. He imagines we all share this dream or would like to. This is heart-warming but will lead to stunted readings of nineteenth-century Russian prose. He’s best, by the way, on Turgenev.

Although Saunders does all he can to get good advice on tricky points of translation, the English-language versions we’re offered of these stories all too often creak and need polishing. All the same, George Saunders has written a marvellously readable and instructive book. He says he hopes it will have ‘lit us up’, although he expects us to rebel against his views. It certainly has lit me up, and I do rebel. And I’m going to read it again.

Comments powered by CComment