- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Addressing identity

- Article Subtitle: Stories of present-day Tasmania

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When as a boy I listened to football on the radio, I would often hear mention of David Harris, a skilful midfielder who played for Geelong and Geelong West respectively in what were then the VFL and VFA. Harris was mostly known as ‘Darky’, not ‘David’. Recently, thanks to a YouTube interview, I learnt that Harris’s parents were Lebanese Australians. While in the interview Harris did not express offence, one can only wonder about the effect on him of this nickname – one he’d had since his own boyhood – based on the colour of his skin.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Born Into This

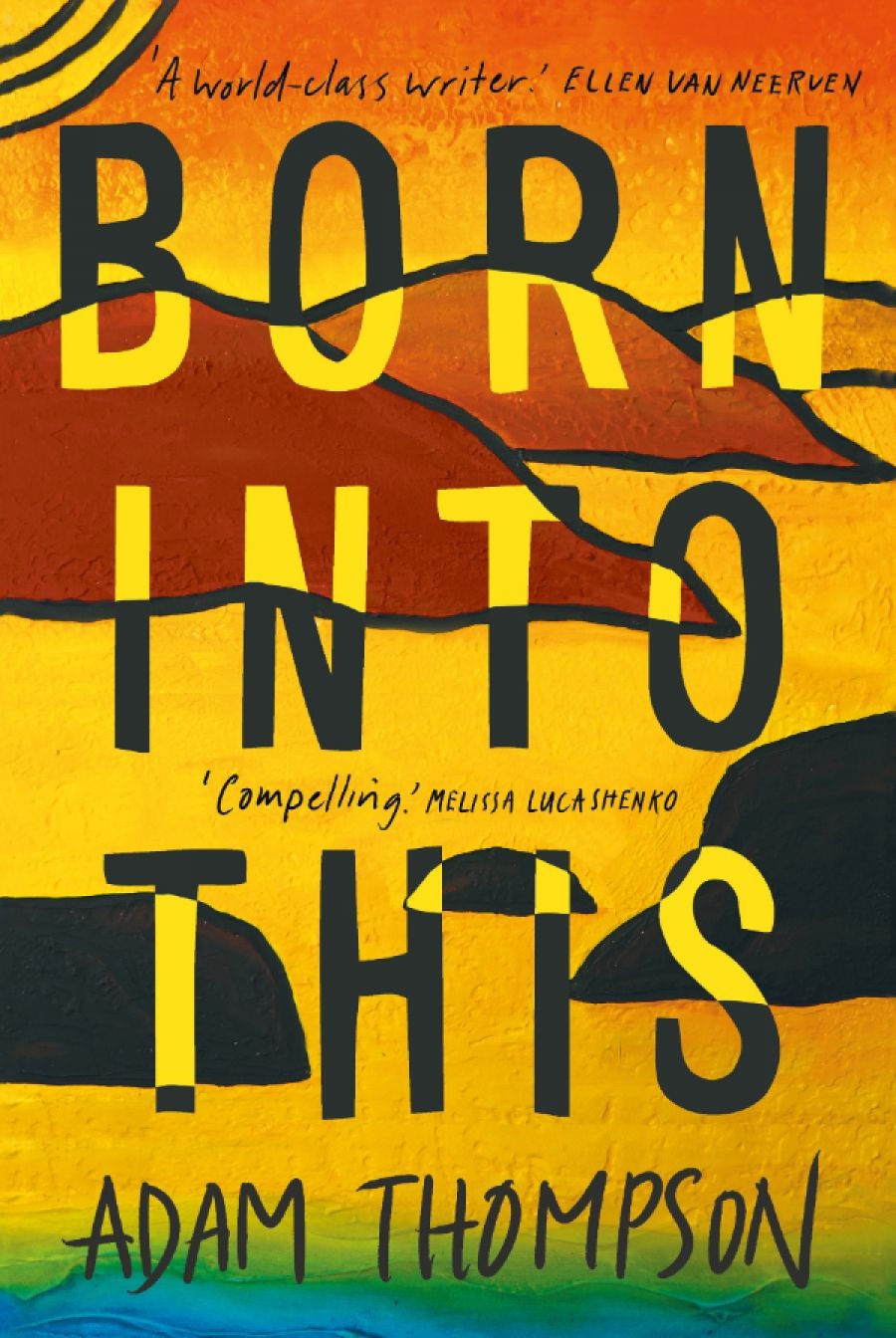

- Book 1 Title: Born Into This

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $29.99 pb, 210 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/oeeD3W

I was reminded of Harris when reading ‘Sonny’, a compelling story in Adam Thompson’s début collection, Born Into This. The narrator tells of his Aboriginal friend Sonny, a gifted footballer from Launceston. In a fit of anger one day on the football field, the narrator calls his friend ‘Darky’; to his shame and regret, this offensive term sticks. Worse names – all clearly pejorative – follow, and the longer-term effects haunt both Sonny and the narrator. Both are diminished by this racist name-calling. The story has implications beyond football (truth-telling, sorrow), but seems all the more pertinent after Eddie McGuire’s extraordinary claim that the leak of a report revealing systemic racism marked a ‘proud day’ for the Collingwood Football Club. As the sorry white narrator in Thompson’s story states: ‘Truth is, it was me who was small and insecure. I was the darky.’

Thompson, an Aboriginal (Pakana) author from Launceston, has written sixteen stories for Born Into This. ‘Sonny’ isn’t the only one told by a character who repents his actions or words. ‘Aboriginal Alcatraz’ and ‘Black Eye’ both have narrators who variously regret their actions or their failure to act. To this we might even add the hardened, unyielding Elder in the opening story, ‘The Old Tin Mine’. Thompson works for the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre and is a passionate advocate for Aboriginal culture, heritage, and land care. The narrators in the above three stories all hold supervisory positions involving protecting culture and the environment. Their grip on each job is tenuous – one bad error and they’re unemployed. But in each case their main fear is not job loss or, for serious neglect, even jail, but shame when facing down Aboriginal people and community. Thompson’s cutting stories finely articulate responsibilities around cultural load, history, and land care, and fear of failure.

Adam Thompson (photograph via UQP)

Adam Thompson (photograph via UQP)

All the stories address Aboriginal identity directly or indirectly, with some tackling the vexed issue of when and how Aboriginality might be claimed. We hear of non-Aboriginal people opportunistically claiming Aboriginal status (‘Descendant’ and the title story), and of families in which one sibling proudly upholds his identity while another, despite having greater material comforts, is in denial (‘Bleak Conditions’, ‘Morpork’).

The title story, ‘Descendant’, and ‘The Blackfellas from Here’ all feature strong-willed women or girls who take on activist roles, promoting heritage and environment or addressing dispossession in their respective stories. ‘Summer Girl’ also has a female protagonist, but here, for the Aboriginal male narrator, she is a well-meaning white girl with limited insight and even less agency: ‘You look at me as a child does a parent, silently begging me to preserve your belief in the good of the world.’ The collection as a whole depicts primarily, and most convincingly, a masculinist world – one of men and boys doing it tough, grappling with identity. Most, nonetheless, have recourse to the riches of culture and heritage, which brings meaning in the face of adversity, and definition of selfhood.

These are potent, revealing stories borne of hard-won experience. A commonality of voice characterises many narratives, with young female protagonists – this may be partly explained by them being more articulate than their male counterparts – given to speech-making. Men and boys tend to be less vocal, sometimes awkward, fumbling for words. This does not, however, preclude effective communication, where a nod, a gesture, a few mumbled words convey all that’s necessary. ‘Aboriginal Alcatraz’ and ‘Time and Tide’ are two excellent examples, with men and boys sharing strong bonds and mutual understanding while maintaining traditional practices such as muttonbirding. The latter story is a particularly affecting portrait of a father and son returning to a remote bay and finding their birding practice undone by climate change and their situation worsened by the greed of an elderly white man – both legacies of colonialism.

With the protagonists often physically isolated – emblematic, sometimes, of dispossession – many settings, particularly those on Bass Strait Islands, bring to mind another Tasmanian-based practitioner: photographer Ricky Maynard.

These are traditional realist stories, closer in form to those of Melbourne writer Tony Birch than, say, to the ‘Aboriginal realist’ (as opposed to the Western notion of magical realist) stories of Ellen van Neerven, in whose story ‘Pearl’, for example, a character literally takes flight with the wind. Thompson’s collection does, however, include the playful story ‘Your Own Aborigine’, set in a near future when non-Indigenous Australians must individually ‘sponsor’ Aboriginal welfare recipients, but the setting is an archetypal one – a group of male tradies gathered around a bar. The language throughout is simple and direct, with occasional (if deliberate) clichés (‘scary as hell’; ‘evil red glow’) offset by vivid similes that ignite the page: ‘stray hairs, like fibres in an optic lamp’; ‘my heritage … bulldozed, smoothed over like warm butter on a crusty scone’.

With Born Into This, Adam Thompson’s stories of present-day Tasmania provide a powerful response to trauma that dates from the horrors of the Black War and continues with ongoing ‘celebrations’ of Australia/Invasion Day. The author has much to say, and I look forward to his next collection.

Comments powered by CComment