- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

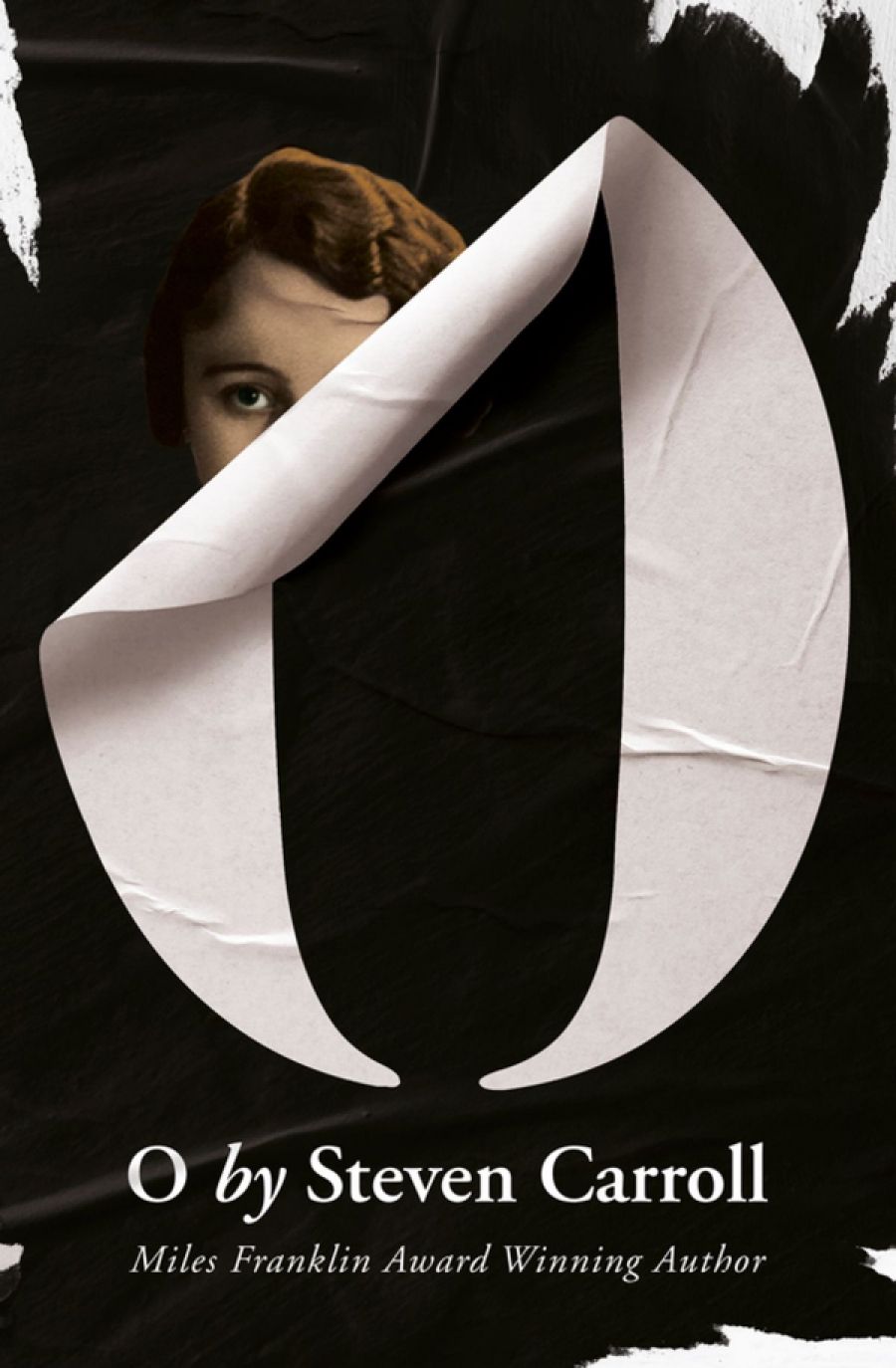

- Article Title: ‘Rolling over so easily’

- Article Subtitle: Steven Carroll’s take on <em>Story of O</em>

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On the back cover of O, we learn that the protagonist of the novel, Dominique, lived through the German occupation of France, participated in the Resistance, relished its ‘clandestine life’, and later wrote an ‘erotic novel about surrender, submission and shame’, which became the real-life international bestseller and French national scandal, Histoire d’O (1954). ‘But what is the story really about,’ the blurb asks, ‘Dominique, her lover, or the country and the wartime past it would rather forget?’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): O

- Book 1 Title: O

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $32.99 pb, 308 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/x99a3y

From the outset, then, readers are primed to look for signs that the occupation of France, as Dominique experiences it, mirrors an erotic novel that foregrounds wilful slavery, humiliation, and torture, and whose protagonist is offered up as a prostitute, apparently for her own benefit. And we don’t have to wait very long: the occupiers of France are quickly identified as dominating presences – the narrator of O calls one of them ‘master’ before Dominique contemplates France under occupation: ‘Rolling over so easily like the whore in the illegal posters pasted up all around the city that call on everyone to rise up and fight: France, a tart with her legs open, gazing up at the sky while a foreign army marches all over her.’ Steven Carroll is not concealing anything here, we think; there is a straightforward connection to Story of O. The question posed on the blurb is half-answered.

A reader who is familiar with Story of O might also know that its real author, Anne Desclos (1907–98), claimed it was written as a kind of ‘love letter’ to the editor and critic Jean Paulhan, who also happened to describe Story of O as a love letter in his remarkable essay ‘Happiness in Slavery’, first published as a preface to the novel. (From Paulhan’s essay: ‘Without doubt, Story of O is the most ardent love letter any man has ever received.’ From Carroll’s novel: ‘And has a man,’ he solemnly asks her, ‘ever received such an ardent love letter?’) The conceit that drives O is that this origin story is only half-true, that Desclos’s novel was also inspired by larger, latent forces.

Across Carroll’s fiction we encounter the imperative to grasp the moment and the world we are tangled up in because they are full of promise and quickly pass us by. Instead of working his way up to this insight, which is his typical strategy, Carroll uses it as a point of departure in O. Dominique sees herself as a ‘forest creature’, conventional on the outside but privately and inwardly wild. She is a cat-like huntress who yearns for the full range of human experience and chases after it boldly. As a young girl, she finds her father’s stash of erotic literature in his library, which becomes a ‘private cathedral containing all things human: the savage and the sublime in equal measure, and equally mesmerising. She absorbed it all.’ She believes in the body, in what it knows and where it directs us.

Dominique is an untamed seductress in search of an equal, someone who can return her passion and participate in her fantasies. Enter Jean Paulhan, a prominent literary editor who looks at the world with wonder. They meet under occupation, when time is out of joint and everything is heightened, and they both believe in France and literature. There is an element of the spy novel in these early sections – quick, suggestive dialogue, the double manoeuvre of revealing while concealing – which produces a ‘new intensity’ and ‘urgency’ for the protagonist and serves to drive the novel forward dynamically. Dominique discovers that she has a gift for improvisation and secrecy, for playing serious games that are not unlike the games of seduction she plays instinctively.

For the first half of the novel, echoes of Story of O enrich the action; Carroll uses the language, themes, and imagery of the original to infuse different scenarios with additional meanings. Dominique experiences the guilt and shame of watching on passively while the occupiers terrify the occupied, and she comes to understand what it’s like to be bound, blindfolded, at the mercy of unknown forces. She decides that ‘We deserve to be bound. We deserve to be beaten ...’ for failing to act when the masters exert control over helpless, terrified victims. When she asks Paul to beat her, it is in direct response to the guilt and shame of occupation.

Story of O is the kind of bracing novel that compels readers to look squarely at things they’d prefer not to see, or at least not to be seen seeing. Carroll writes an altogether different kind of fiction that is quietly concerned with the power and beauty of ordinary life and the generative power of memory and art, all rendered in sensitive and recognisably ‘literary’ prose. On the face of it, a Carroll novel about the genesis and afterlife of Story of O is a curious prospect, and O lives up to expectations. It’s weird, in good ways and bad: the generic slipperiness (spy novel, love story, historical fiction) enlivens much of the first half – we don’t quite know what we’re reading or where it is all headed – and the subject offers ample opportunities to gesture at contemporary brands of censoriousness or taking offence with appropriate contempt.

But O suffers from an amplified version of already-prominent elements of Carroll’s fiction: repetition (of phrasing, image, theme, metaphor) and the impulse to make everything explicit. This is a wonderfully inclusive habit, since even the most distracted reader cannot fail to keep up with the action or miss the thematic gist. But it can also be jarring, and the strategy is badly overplayed in O. From the surprisingly unsurprising final sections to the concluding ‘Notes on the Novel’, we are treated to a rearticulation of something that is obvious from the start. Carroll employs the grammar of swelling music as the novel putters out, extracting as much sentiment as can be mined from the novel’s stellar beginnings, but the effect is much like a protracted attempt to conjure an orgasm that never arrives.

Comments powered by CComment