- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A network of compulsion

- Article Subtitle: The riddle of reconciliation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What kinds of stories are possible now about a mission community at the height of the assimilation era? How might scholars narrate the lives of religious women who ran an institution for Indigenous children?

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): A Bridge Between

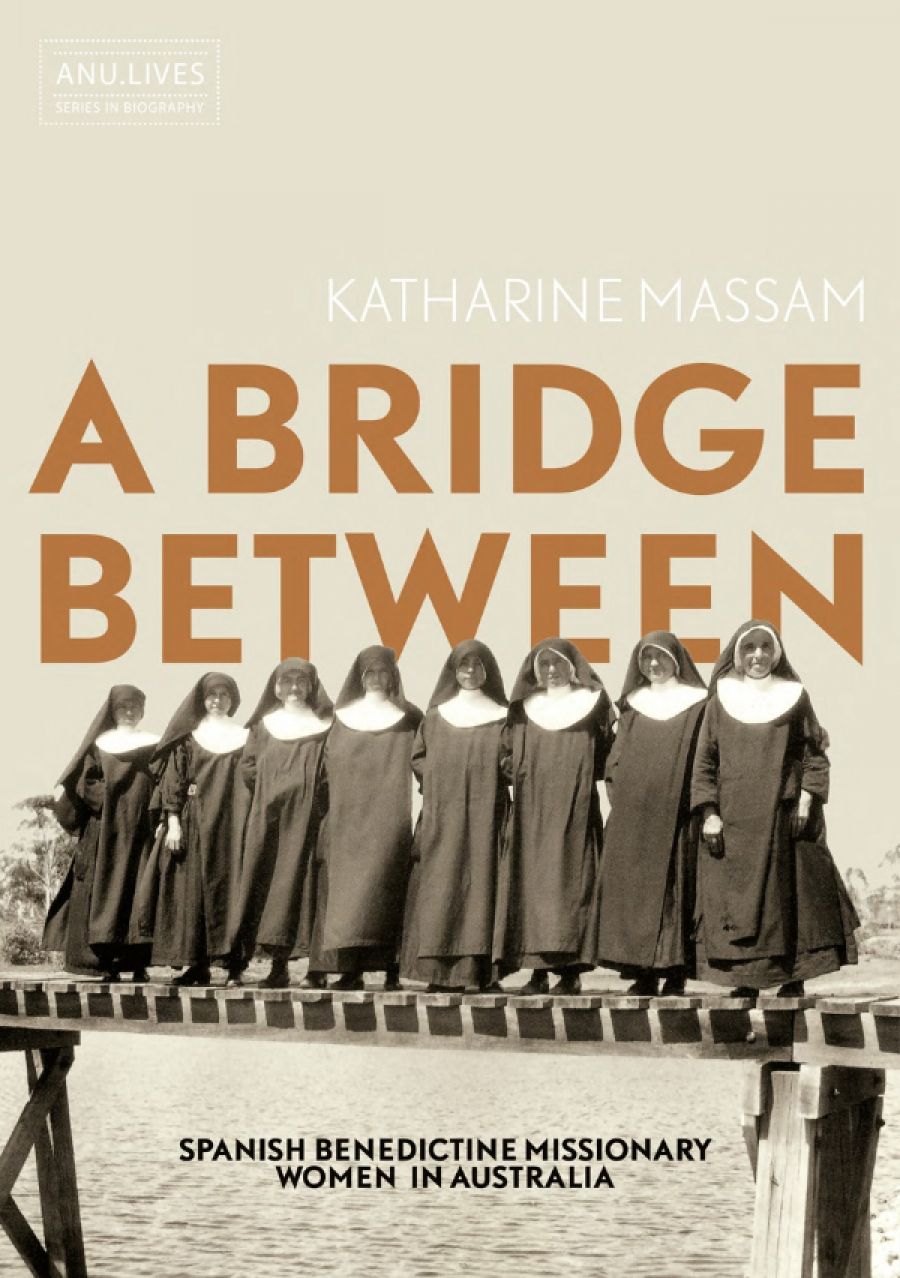

- Book 1 Title: A Bridge Between

- Book 1 Subtitle: Spanish Benedictine missionary women in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: ANU Press, $65 pb, 390 pp

Historian Katharine Massam has lived with these questions for more than twenty years. Her long-awaited monograph, A Bridge Between, is not so much a solution as a response: a delicate, unsettling story told largely ‘in the language of tears’. Begun in the aftermath of the Bringing Them Home report (1997), and completed as the Uluru Statement from the Heart (2017) reverberated across the nation, this book is ultimately a hopeful search for a reconciling kind of memory.

As the subtitle indicates, A Bridge Between is focused on a very particular group of people: Spanish Benedictine missionary women, active in Australia between 1904 and the early 1970s. There were around sixty-five sisters in all; all of them connected to New Norcia, north of Perth, Australia’s first and only monastic town.

Already, this is challenging territory – for collective memory and for historical scholarship. New Norcia was established as a Benedictine mission, in Yued Noongar country, in the mid-nineteenth century. Founded by Dom Rosendo Salvado, it was initially staffed by religious brothers. By the time religious women joined the mission, in 1904, there were two institutions for Indigenous children on site: St Joseph’s ‘Native school and orphanage’ for girls, where the sisters went to work, and St Mary’s for the boys.

The Abbey Church of New Norcia (Gnangarra/WikimediaCommons)

The Abbey Church of New Norcia (Gnangarra/WikimediaCommons)

There have been many profound and painful experiences associated with New Norcia, since the mission’s beginnings. Massam knows she cannot recover or bear witness to them all. She has listened deeply to Noongar women who lived at St Joseph’s as girls. A Bridge Between is informed by those relationships and what she has learned from them – about control, neglect, suffering, and other things. But as a non-Indigenous scholar, Massam does not presume to distil the messy realities of life as ‘a St Joseph’s girl’. Massam therefore restricts herself to the Benedictine missionary sisters who came to work at St Joseph’s, and in some cases also at Kalumburu Mission in the Kimberley. As the leading historian of Catholic women’s spirituality in Australia, Massam is well equipped to draw out the depth and complexity of their collective biography.

A history of a few dozen Benedictine sisters may still seem niche, but Massam engages with many of the deeper themes in Australian historical writing. She shows that these women had an unusual and often risky relationship to the world around them. They were Catholic in a Protestant-majority society; typically Spanish-speaking people in a corner of Britain’s empire. As mostly Mediterranean folk, they had an ambiguous place in white Australia’s racial hierarchy. Who were these women? Why did they come here? And how did they understand their vocation in Australia?

One of Massam’s clearest achievements is to have coaxed the details of these women’s lives from a dispersed and disrupted archive. Much was discounted as unimportant and went unrecorded, even in their own time. The documentary traces that remain are scattered across Australia, Spain, and Belgium. Massam has pieced these together with exemplary patience. She has also ‘read’ the physical site of New Norcia and summoned new meaning from scores of old photographs (about eighty are reproduced in the book). There are hints that her conversations with several of the sisters were mutually transformative.

Perhaps because certain details were so hard won, at a few points they threaten to overwhelm Massam’s narrative. Mostly, though, they bring otherwise forgotten women into vivid remembrance. We meet sisters who, as teenagers in the 1940s, left their homes and families in the north of Spain for a life of prayer and work in Western Australia. We see their missionary efforts shifting and unfolding, within toxic policy contexts that they usually did not influence, let alone determine. We even get a glimpse of what it meant for Marie Willaway, a Noongar girl, to enter religious life and become a Benedictine Sister herself. Some things, of course, remain unknown, but we see these women’s lives in motion.

In all this, Massam is especially attentive to the lived experience of faith and vocation. These can be difficult realities for Australians to imagine in our apparently secular century. But Massam leans in, sympathetically, to the challenge and even the gift of Christian belief. The result is a landmark in the study of Catholic communities in this country, and female religious more generally.

At the same time, Massam’s fundamental commitment to women’s experiences animates A Bridge Between. She does not overlook the heavy domestic labour that loomed so large in the sisters’ lives, as they cooked, sewed, mended, and washed clothes for the entire New Norcia community. She recognises the St Joseph’s laundry, a place as utterly marginal to ordinary record keeping as to the public memory of the mission, as a place of high drama. In the laundry, vocations were tested, bodies exhausted, and the boundaries of race and gender debated and defined. There, too, Massam faces up to one of the deepest difficulties of this history. For the sisters, work, like prayer, was central to Benedictine life and spirituality. Even in the laundry, they laboured with a sense that their choices were part of some divine plan. It was a matter of sacrifice and obedience, a trusted path to holiness.

But what of the girls who worked alongside them, shouldering the same domestic duties? St Joseph’s was part of a network of compulsion that wreaked havoc on Indigenous families. There is evidence that some parents saw it as a refuge of sorts, the lesser of various evils. There are testimonies, too, of deep suffering: St Joseph’s was riven with griefs and traumas that some former residents continue to live with.

Telling the story of the missionary women is not a matter of weighing these experiences against each other. Massam sees her task in terms of paying attention, especially to the relationships forged at St Joseph’s and that somehow endure beyond it. These relationships do not erase conflict, or resolve all the pain and ambiguity. But in their commitment and their complexity, they provide a context for deep – even holy – listening.

A Bridge Between invites the reader to listen and reflect on the lives of the missionary sisters, almost as a spiritual discipline. In Massam’s compelling vision, this work of remembering – without shying away from darkness, yet in search of shared horizons – is an act of hope for reconciliation.

Comments powered by CComment