- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Feminism

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘We are the men in this situation’

- Article Subtitle: Overcoming feminism’s racial distortion

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The most difficult thing for white, straight, able-bodied, middle-class, cis women to accept seems to be that feminism was designed for them. But the reality is that from a suffrage movement that forced Black marchers to walk at the rear to the ‘girlboss’ CEOs who bully their poorly paid underlings, the cause known as ‘feminism’ has long been dominated by the aspirations of an élite group of women.

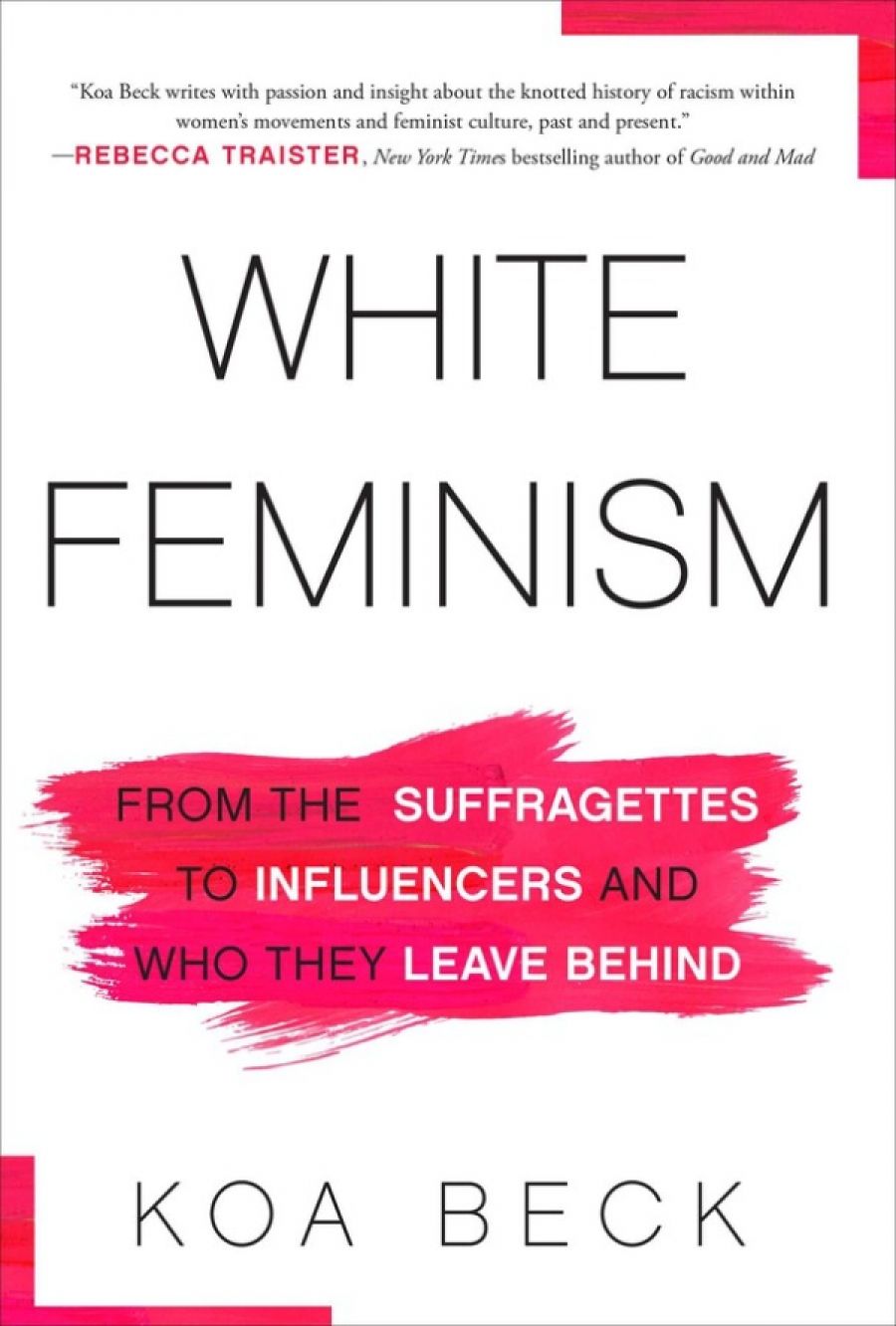

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): White Feminism

- Book 1 Title: White Feminism

- Book 1 Subtitle: From the suffragettes to influencers and who they leave behind

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon & Schuster, $32.99 pb, 319 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/155BM6

This is the history Koa Beck diligently traces in White Feminism: From the suffragettes to influencers and who they leave behind. She illustrates how, for centuries, this dominant version of feminism has combined the twin forces of white supremacy and capitalism to advance the interests of a select few while leaving behind the working classes, ethnic minorities, trans and queer people, and those with disabilities – not by accident but by design. Again and again, wealthy, white, heterosexual women have forced everyone else to take a back seat while they set the priorities of the women’s movement. Beck asks white feminists to consider that when it comes to, for example, debates over the inclusion of trans women at the élite American women’s colleges she herself attended: ‘We are the men in this situation.’ This history has led to a contemporary reality in which, for every white feminist CEO who is ‘leaning in’ in the boardroom, there is a poor woman of colour caring for the CEO’s children and cleaning her house so she can climb the corporate ladder.

Beck points out that the troubling regression in gender equality during the pandemic, particularly within heterosexual households, where the burden of cleaning, feeding, schooling, and working under one roof has fallen disproportionately heavily to women, is because the solutions white feminism has come up with for the twenty-first century were no real solutions at all. ‘Because white feminism wasn’t made for this real life with real challenges and very real barriers to economic stability.’

Koa Beck (photograph by Martha Stewart)

Koa Beck (photograph by Martha Stewart)

In Beck’s telling, white feminism is the ethos of individual success and self-optimisation. At its heart is a neoliberal logic: ‘I have value because I have money.’ What this means for those without money – because of racist practices, the marginalisation of queer and gender non-conforming people, or the legacy of colonialism, among myriad other structural barriers – is that they are simply not trying as hard as the thin, white actress on the magazine cover or, say, Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg.

Beck comes from a successful background in women’s media, having worked at Vogue and Marie Claire before landing a job as editor-in-chief of the irreverent feminist website Jezebel. Many of her insights come from her experience toiling in the women’s media content mines, trying to smuggle stories about trans men’s reproductive options alongside ones with headlines like ‘Women Are Allowed to be Mean Bosses, Too’.

At once witty and authoritative, the book is packed with pithy explanations of the phenomenon that is white feminism, from ‘social justice for all and equal pay but also, this is all just really about me’, to ‘the idea that radical change will come one woman at a time, in a nice corner office, in a leadership role, in a woman with a sharp red lip and a severe heel’.

It is also replete with the jargon taken straight from the white feminist corporate sphere she so handily eviscerates elsewhere. We hear of social media posts that ‘scale a tonality of ambition-fostering’. Some of the metaphors are particularly tortured. ‘The Feminist Lady CEO media hunt and Lean In set into motion a moving formula that now resounds so loudly over Pinterest and Instagram that it’s hard to believe it wasn’t always there,’ she writes. But can a formula move or indeed be set into motion? Can it resound at all, never mind over Pinterest?

Beck writes from an American perspective, but there is much in here that can be applied to Australia. With its own bleak tradition of dispossession, genocide, and the upholding of white women’s ‘purity’ as a stick with which to beat minorities and First Nations people, the continent known as Australia is the logical stomping ground for white feminism, evident everywhere from the deaths in custody of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to the pages of Mamamia. The limitations, and often the violence, of this ideology have been well documented by a number of Australian feminist thinkers, including Aileen Moreton-Robinson in Talkin’ Up to the White Woman (2000), Sara Ahmed in Living a Feminist Life (2017), and Ruby Hamad in White Tears/Brown Scars (2019).

This is in part because for as long as there have been white feminists, there have also been those with a more inclusive outlook. Beck draws on the 1940s meat boycotts led by Jewish housewives, the disability rights sit-ins of the 1970s, the Native American-led Dakota Access Pipeline protests, and the push for a Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights to present an alternative feminist vision based on collective organising and solidarity. It’s an energising prospect: surely we deserve more than a world in which Audre Lorde quotes are used to sell us underwear.

While there is a long history of critiquing the limits of feminism, Beck offers what may become a definitive account of white-feminism-as-ideology – where it came from, why it persists, and how we might overturn it. She has undertaken the thorough archival work necessary to present a bulletproof case that white feminism does not work and that it should be discarded. It is now – and has long been – on those of us for whom this movement was built to work out how to be ‘a feminist who is white, as opposed to a white feminist’ and lean out. As she concludes: ‘We won’t wait.’

Comments powered by CComment