- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A different kind of loneliness

- Article Subtitle: The story of two complex Australian women

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

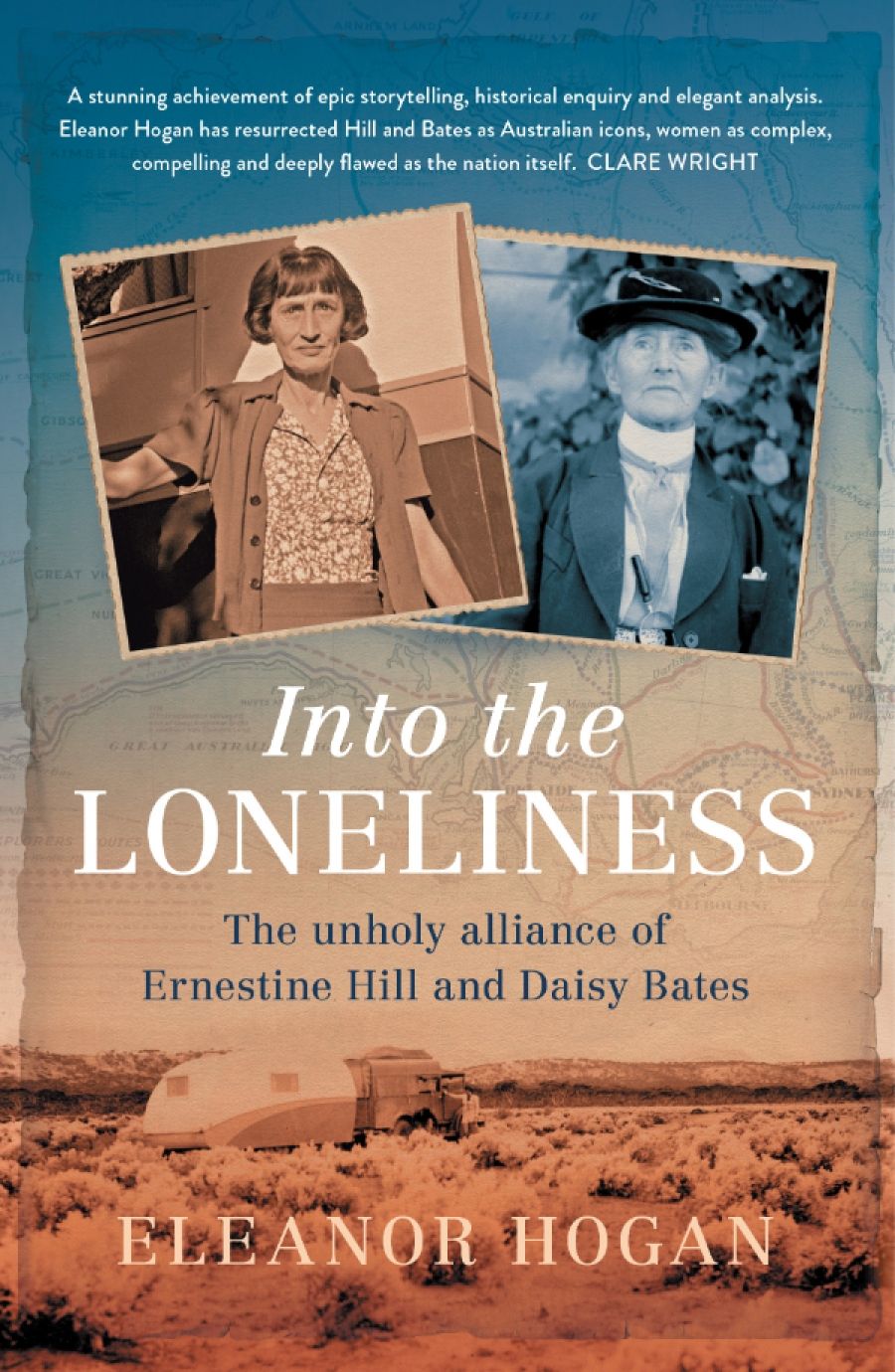

Into the Loneliness is the story of two Australian women, opposites in temperament, who eschewed the conventional roles expected of women of their eras, lived unconventional lives, and produced books that influenced the culture and imagination of twentieth-century Australia. The book focuses on their complicated friendship, and on Ernestine Hill’s role in assisting Daisy Bates to produce the manuscript that was published in 1938 as The Passing of the Aborigines, which became a bestseller in Australia and Britain. Hill, a successful and popular journalist, organised the anthropological material and ghost-wrote much of the book, for which Bates privately expressed her gratitude, while not acknowledging it publicly.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Into the Loneliness

- Book 1 Title: Into the Loneliness

- Book 1 Subtitle: The unholy alliance of Ernestine Hill and Daisy Bates

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 432 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/3PPWMA

Bates emerges as a wilful, self-mythologising, and charismatic personality, while Hill is a self-effacing romantic, a poet–journalist already embarked on a literary career reporting and idealising the lives and characters of remote Australia. Hill’s own book The Great Australian Loneliness, based on five years of wandering in the outback and published in 1937, became an instant popular success. As the subtitle of Eleanor Hogan’s book suggests, Bates and Hill were made for each other.

Bates railed against the male-dominated institutions that refused to recognise her ethnographic research or her potential to play a formal role in the welfare of the Aboriginal people among whom she lived. A self-appointed dispenser of mercy and largesse, Bates was a law unto herself, marrying twice, possibly three times, without bothering with divorce, abandoning her son, and embarking on her ethnographic study of Aboriginal people without training or experience.

While Hogan’s forensic research details the when, where, and how of Bates’s activities, the why of a lively Irish girl transforming herself into Kabbarli (the name given her by Indigenous people), the Daisy Bates of legend, remains an enigma. Bates seems to have thrived on her otherness. Arriving as a young woman in the protean society of late nineteenth-century Australia, she immediately set about reinventing herself. There was something impervious about her, an inability to submit to restraints or social rules.

Ernestine Hill with swag, leaning against large ant hill, Kimberley, Western Australia, c 1931. (University of Queensland. UQ:734073)

Ernestine Hill with swag, leaning against large ant hill, Kimberley, Western Australia, c 1931. (University of Queensland. UQ:734073)

Hill was a restless spirit, but her occupation allowed her to turn her wandering into stories for which she was paid the going rate, journalism being one of the few professions that did not pay women less than men for the same work. For the women who managed to extricate themselves from writing the social pages, journalism offered independence, travel, adventure, and a public voice. Hill turned her gender to advantage, travelling to the remotest parts of the country, an exotic and welcome visitor to the mining camps, homesteads, and pearling and fishing towns whose denizens she romanticised and wrote about to feed the urban hunger for news from the wild interior. The archetypal trouser-clad, cigarette-smoking, intrepid female reporter, she journeyed with her swag and typewriter to the furthest outposts of the nation, a model for the rising generation of aspiring women journalists.

A woman travelling alone in remote places is an enduring trope of risk and danger, yet none of these women – Daisy Bates, Ernestine Hill, or the author herself – encountered threats. Instead they were offered the hospitality and kindness of strangers. As Hogan observes of her solo travels, ‘If anything, I was more at risk from my own practical ineptitude than a malevolent white male battler.’

The loneliness in the title of The Great Australian Loneliness describes a state of physical rather than existential isolation. Hogan is exploring a different kind of loneliness, as pertinent today as it was for Hill and Bates, inhabited by a semi-itinerant cohort of wandering women writers eking out an existence along the seams of cultural overlap – members of what Hogan calls the precariat: people, especially single women, whose lives are contingent on unpredictable and meagre resources.

Both Bates and Hill produced bestselling books that influenced the ideas and attitudes of the day. Both lived in increasingly straitened circumstances, surviving on tiny stipends, shrinking royalties, and the charity of friends. Both died broke, an object lesson for aspiring writers today.

Into the Loneliness is a remarkable piece of research and writing, and a labour of passion and perseverance, given the vast, disorderly archives Hill and Bates left behind. From these archives, Hogan has created an immensely readable narrative, structured as segues between the individual stories of each woman and the episodes in which their lives intersect. The author is intermittently present, seeking insight into contemporary Indigenous attitudes to Bates, and reflecting on her own experiences as she travels in her campervan to the locations frequented by her subjects.

The women who emerge from the personas created by the books they wrote and the lives they led are more interesting and less admirable than the legends. Bates was a genuine rebel – mercenary, missionary, misfit and probably mad to boot. Her increasing eccentricity may have been due to the onset of dementia caused by malnutrition. There is a stomach-turning description of Bates consuming her daily protein intake of a raw egg congealing in a cup of hot tea. Whether she was lonely is hard to say. She made a place for herself among people who did not contradict her sense of superiority and who provided her with companionship and ethnographic fodder. She enjoyed the company of birds, animals, and children. Bigamist, fabulist, narcissist, half-mad, half-blind, tough as old leather: Daisy Bates lived to the age of ninety-two and remained opinionated and indomitable to the end.

Ernestine Hill (née Hemmings) was an inadvertent rule-breaker. At the age of twenty, she met Robert Clyde (R.C.) Packer, forty, married, progenitor of the Packer media empire. Although his paternity was never acknowledged, Hill’s son Robert was born in 1924, when she was twenty-five. The birth of an illegitimate child freed her by default from a conventional career. Assisted by her mother and aunt in caring for her son, she called herself Mrs Hill and embarked on the restless wandering that would fuel her journalism, support her family, and render her homeless.

Both women wrote about Indigenous Australians through the lens of their times. Bates shared a co-dependent relationship with the Indigenous people she studied. Her claims of cannibalism were debunked and her abhorrence of half-castes deemed racist and obsessive, but her ethnographic observations and recording of language contained much of value. Hill’s notes describe sites where massacres took place, and her writing is inclusive and insightful about the Indigenous people she encountered.

In their flawed and idiosyncratic ways, Daisy Bates and Ernestine Hill attempted to absorb the loneliness and embrace the uniqueness of the continent and its inhabitants. In paying homage to their lives, Eleanor Hogan has given us a rich and thought-provoking insight into two of the most interesting women Australia has produced.

Comments powered by CComment