- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The adventures of ‘Hanging Bill’

- Article Subtitle: An elegant book about the pull of Uluru

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The distinguished historian Mark McKenna has written an elegant and hungry book about the pull of Uluru, that place of mysterious significance to Australians, black and white. Of course, in recent times, the Uluru Statement from the Heart – the heart that had a stake driven through it the moment it was entrusted to the most powerful whites in Canberra – is a complicated domain of passion and polemic. McKenna’s work, pro-Aboriginal and postcolonial in spirit, is itself an addition to the long history of romancing Uluru, albeit with a focus on a hero who seems like an anti-hero by the time this book is done.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

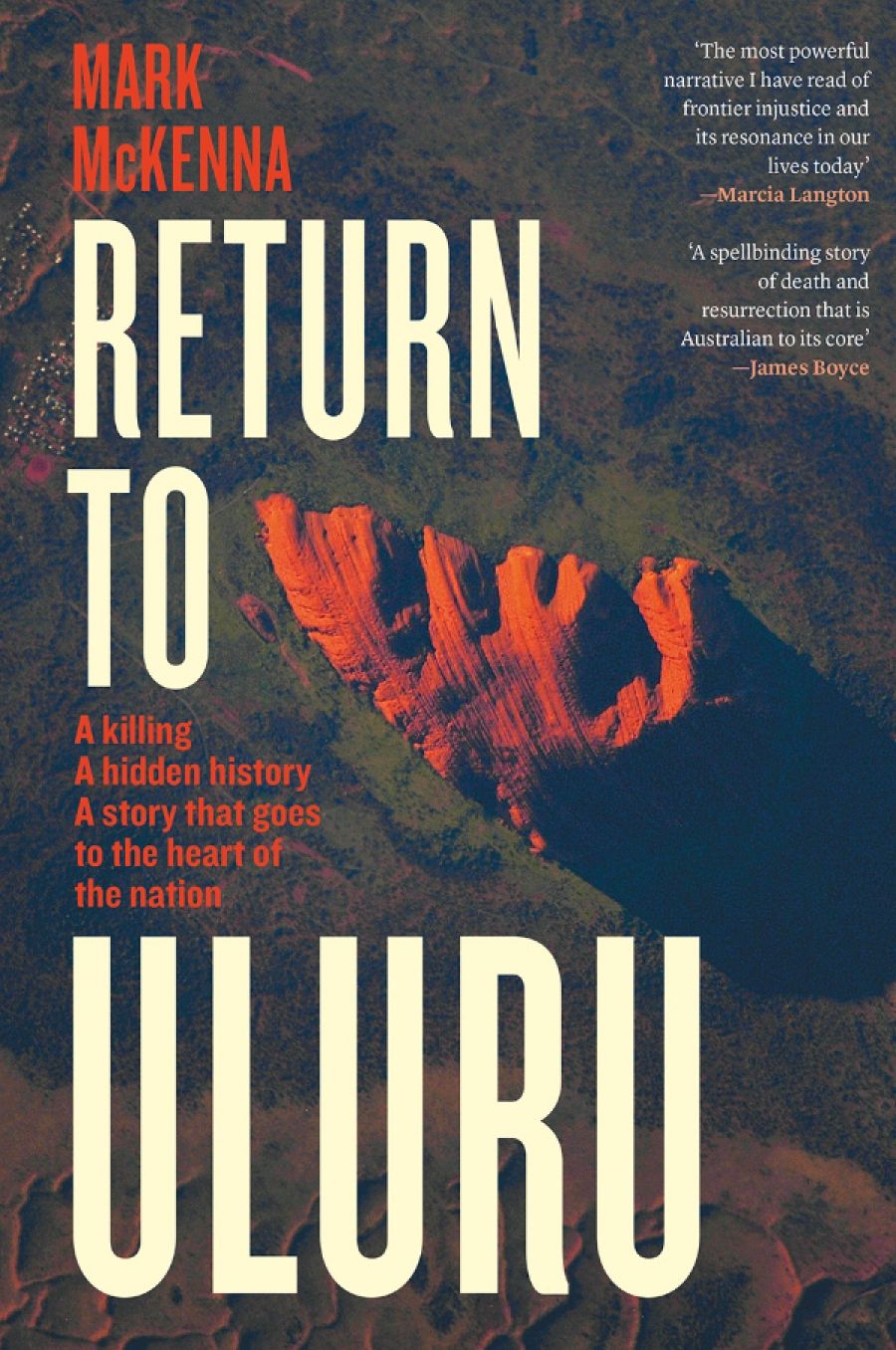

- Book 1 Title: Return to Uluru

- Book 1 Subtitle: A killing, a hidden history, a story that goes to the heart of the nation

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $34.99 hb, 256 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://booktopia.kh4ffx.net/GjjJ1B

Bill McKinnon was, once upon a time on the frontier, the chief policeman, a man much fêted in his day, even though the authorities knew him to be a murderer and a liar with regard to the ‘fearful blacks’ he had in his charge – men often chained together by the neck and tied to trees when they were not on the run from him on his camels, along with his tracker, whose nickname, Carbine, said everything. McKinnon was a cock-strutting hero of the ‘Killing Times’, an epoch by then in full swing with the Coniston massacre of 1928, a slaughter he chose to underestimate.

Ever the colonial master (as well as an amateur photographer), he fancied himself in uniform, along with pith helmet, the get-up he sported in Rabaul, where he first dealt with ‘ill-disciplined natives’ who could be hanged in full view of their community. In this beautifully structured and illustrated narrative, there’s a shot of McKinnon dressed in his whites, standing at the cairn at the top of Uluru, holding onto it like a ship’s captain. I snorted when I saw it, and then again when I came to the priceless image of him still at the top, but immersed in a muddy rock hole, as grotesque a figure as something in a Francis Bacon painting.

How a man can fall, I thought, suppressing embarrassment at once having climbed the rock myself. Soon after the Handback, and before my own book on Uluru, I had panted my way to the top, where a book for travellers lay open to sign. I could not bear to put my own name down. Instead, I signed in as William Buckley, the escaped convict who lived for thirty-two years with the Wothaurung people in the Port Phillip District, whose life I was immersed in for the purposes of writing a long poem.

The Centre – the spirit of Uluru, if you like – is sooner or later bound to reveal our errors of understanding and self-presentation, the vanities and nightmares. One error happens as soon we blur notions of heart and centre and sacred, as if each of those terms belongs to an exotic marriage of Western and Indigenous thinking and feeling. McKenna seems to fall for this kind of syncretism when he writes: ‘What had long been the Anangu’s “holy place” and “most sacred spot” had gradually become the entire nation’s centre, at once geographical and spiritual.’ McKenna’s quest – his hunger – is for something he refers to as the ‘interior’ Australia; this as distinct from history as it has been written from the ‘edge’, the crucial term in the title of his last book, which hugged the coast.

I don’t wish to disparage yearnings to go ‘inwards’, except to say that the conceptual challenge is not to quest too much at once. At the very least, the narrative of the Australian interior needs to be cognisant of the complicated Aboriginal grounds of meaning. For instance, Uluru before the present period was no more ‘central’ than many other places. It was one of many nodes of important ceremonial meanings on a polycentric map. Indeed, Uluru was less significant, in terms of songlines, ceremony, and totemic creatures than its near neighbour, Kata Tjuta. Couching this truth tactfully (within the limits of what the land claims call ‘restricted material’) might temper a nation’s childish need for ‘a centre’, when what is really being sought is a less emblazoned realm of the ‘sacred’ – more in keeping with what McKenna himself describes as ‘the country’s supple, interconnected Indigenous heart’.

Leaving aside the rhetorical uses and abuses of anthropology on both sides, McKenna’s narrative is in tune with the faith in truth-telling and tenderness that drives the Uluru Statement from the Heart. His revelatory narrative can be baldly stated: the true nature of McKinnon’s shooting of an Aboriginal man, Yokununna, in a cave at the rock in 1934, was covered up by an official inquiry in 1935. Two other men McKinnon went after, Paddy Uluru (Yokununna’s brother) and Joseph Donald, kept running and laid low for half a century, the sound of gunfire ringing in their ears. And not only in the ears: in the hearts of kin all that time. ‘Death is still in people’s minds,’ as Justice Toohey wrote in the 1979 Uluru land claim.

After the celebrations of the Handback, the two escapees emerged with what they had witnessed: namely, the fact that McKinnon had recovered a wounded Yokununna from the cave, only to shoot him point-blank in the head. ‘So they shot him. They shot him in front of me,’ Joseph Donald told the filmmaker David Batty out at Docker River, west of Uluru, whence he had fled. The video is now available on YouTube. By pointing readers to it, McKenna powerfully closes the gap between the print record and the spoken, lived experience.

Inspector Bill McKinnon, Northern Territory police, Jubilee Day Parade, Alice Springs (c.Stuart Tompkins, 1951) National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne (Accessioned, 1984. This digital record has been made available on NGV Collection Online through the generous support of Professor AGL Shaw AO Bequest)

Inspector Bill McKinnon, Northern Territory police, Jubilee Day Parade, Alice Springs (c.Stuart Tompkins, 1951) National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne (Accessioned, 1984. This digital record has been made available on NGV Collection Online through the generous support of Professor AGL Shaw AO Bequest)

There is all manner of atrocious detail on the way to this narrative climax. Often we are reminded that a policeman of the day had to bring the head of a deceased person back to Alice Springs. How else was a man to be identified? McKinnon severed heads with a shovel. His tool of choice when it came to pesky dogs was a tyre lever, which flattened skulls. It was when he found a bullet rattling around in a human skull at Mt Connor that his ‘epic manhunt’ began. The man supposed to have died at the hands of tribal relatives had been killed by someone with a white man’s gun. Taboo on the frontier! The chase began, and McKenna embraces it with the gusto of an adventure story that includes praise for the hardy policeman’s stamina, as well as native guile.

McKinnon’s vanity shows through everywhere, not least in the memoir that McKenna uncovered at McKinnon’s daughter’s house in Brisbane a few years ago – a scoop if ever there was one, so much so that McKenna abandoned his planned general essay on the centre in order to write this biographical sketch as a kind of primal foundation myth that taints Uluru.

More prosaically, McKinnon was a tight-arsed stickler for keeping a log of daily events, on and off the job. His archive was replete with historical documents and memorabilia, including the complete films of Marilyn Monroe. I wish McKenna had cited passages rather than snippets from the memoir. Who knows what is really there? McKenna hints at the savage paternalism that coexisted with the policeman’s love of his wife. When his first wife was still in the labour ward, McKinnon wrote to his brother saying that his visits were ‘a real morbid experience’ and that he would have been ‘much happier in the pub instead’. Each day his mother in law, who was also in hospital, used to tell him how she might not ‘see the night out, but unfortunately’, the cruel bushman added, ‘she is not a woman of her word’. McKinnon’s next wife was twelve years younger than him. This ‘matrimonial knot’, teased Brisbane’s Sunday Mail, was another adventure for ‘Hanging Bill’.

Return to Uluru has redolent photographs of McKinnon with his bush mates, among them Bob Buck, the man who had famously recovered the lost prospector Harold Lasseter. Buck, a laconic man with an armoury of guns on his dining room wall, was renowned for his bevvy of young Aboriginal women who gave birth to his offspring, and whose condition for sexual congress was improved when he used his bush knife.

In my book, The Rock: Travelling to Uluru, I called Buck the ‘Bastard from the Bush’, which prompted Max Cartwright (who made the road to the rock) and Peter Severin (who owned Curtin Springs station and opposed the land rights movement) to pay me a visit as I was conducting a writer’s class in Alice Springs. They turned up out of the blue, formal and tense. I served them tea and introduced them to the class, and eventually they explained they were there because of what they called my hostility to white settlers and because of what I had written about Bob Buck. ‘He was a mate of ours,’ they cried, to which I replied, ‘Well, he would not have been a mate of mine.’ They demanded to know why, so I mentioned the knife. They stared at me, apparently unmoved. The conversation we had to have was joined by Alexis Wright, the sole member of the class who seemed to know what to say in the face of barbarism.

McKenna admirably cites Conradian horrors. He writes decorously, with painstaking accuracy. But he delves insufficiently into the psyche of the ‘lonely white males’ whose company McKinnon so loved over the billy tea. Nor does he unpack the frequently mentioned ‘humanitarian’ lobby down south, or the compassionate ethos of the best missions stations at the time. As a result, the shameful heart of the Centre is left intact, gothic and remote. I think I wanted an Australian book that could be read in the company of Ashis Nandy’s The Intimate Enemy: Loss and recovery of self under colonialism (1983), the famous dissection of colonial consciousness, its ambivalence and unconscious, in India. To live well with the project of the Uluru Statement, everyone needs to be in touch with the most complex truths about themselves.

Comments powered by CComment