- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: 'Would you be free for dinner?': An evening with John le Carré

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: 'Would you be free for dinner?'

- Article Subtitle: An evening with John le Carré

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The voice on the telephone, not brusque or curt, came straight to the point. ‘How long are you in London for? And would you be free for dinner this Friday?’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

After the Auckland rehearsal, Alfred had stayed on the platform to run through some of the works he was preparing for his solo recital. During a pause I cautiously approached him, LP tucked under an arm, and tentatively wondered if he might be so good as to sign it. I can still see the expression on his face as he abruptly asked: ‘Which one is it?’ Grabbing it from my hand, he peered at it, relaxed, and said: ‘That’s all right. I’ll sign that.’ (Thank God, I have often thought, for Franz Liszt and his Hungarian Rhapsodies.)

This initial demonstration of acceptable musical taste led to an invitation to get in touch whenever I was in London, along with his private phone number and address. I followed up in 1973, and this has since morphed into a friendship and even collaboration lasting just on fifty years.

Beginning in the 1970s, there were dinners and post-concert parties with a wide selection of figures from various musical and social spheres: Tamás Vásáry, Al Alvarez, Isaiah Berlin, Eric Hobsbawm, Till Fellner, and Imogen Cooper, among others. But some names were less familiar. That was the case back in 1983. I said we would very much like to take up the dinner invitation, to which Alfred replied: ‘You’ll be interested: David Cornwell is coming as well.’

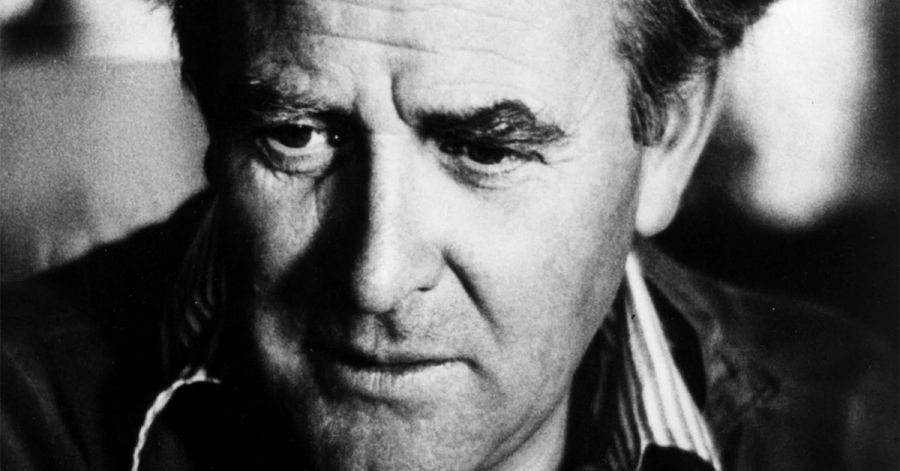

John le Carré, 1965 (RGR Collection/Alamy)

John le Carré, 1965 (RGR Collection/Alamy)

My ‘Oh, right’ was clearly taken as some sort of indication that the name was familiar to me – which it certainly was not. Once off the phone, and without the benefit of Google or any access to libraries with Who’s Who, my mind remained blank. The name sounded vaguely familiar, but I couldn’t think of a conductor or instrumentalist or cultural commentator with that name. The next few days were marked by the occasional ‘I wonder who he’ll turn out to be?’ and ‘Oh well, Friday will clear it up.’ Which it did, but not the way I’d expected. Wandering into Waterstones in Hampstead (where Alfred lives) before the dinner, my partner and I were confronted by a book table heaped with copies of The Little Drummer Girl by John le Carré. The penny crashed. Neither of us had read the book, and to say that we were both kicking ourselves for not having spent the week doing so would be an understatement.

I needn’t have worried. Alfred introduced us to David and his wife as ‘old friends from Adelaide’. Before I could actually presume on David’s lack of familiarity with Australian geography, he said: ‘Adelaide? Really? I don’t suppose you’d happen to know my old friend Jimmy Kirkland and his wife?’

As it turned out, I did. Jimmy (James) I had met just once, but I knew his wife quite well in her professional capacity as Daphne Grey, a long-time stalwart of the State Theatre Company, whose performances both for it and other local companies I had regularly reviewed. I was aware that Jimmy was a pathologist but knew little of his past. ‘How do you know Jimmy?’ I asked.

The tale that followed should have been recorded. David, it turned out, was a brilliant mimic. He had Jimmy’s Scottish accent and demeanour down to a T – as well as his gift for storytelling. If my recollection of the story comes out along the lines of Poo-Bah’s ‘bald and unconvincing narrative’, it’s no fault of the original storyteller’s.

In the early 1960s, David was in Bonn, attached to the British Embassy. His account of his day-to-day duties was, he insisted, much livelier in the retelling than in reality. He would go into the office on weekends to escape the ‘attractions’ of Bonn and to do some writing away from his colleagues. He also used the Embassy address as first call for responses to his letters to British publishers.

One Saturday he went into the Embassy, checked his mail, and found a letter of acceptance of the manuscript of his first novel, Call for the Dead. ‘Can you just imagine it? The prospect that I might even be able to leave the Embassy job and become a writer? I was almost jumping out of my skin.’ (This from a very urbane and composed star author, who seemed unlikely at any stage to have indulged in such activity.)

‘I really needed to tell someone why I was so excited. But who? Certainly not the German concierge figure on the desk downstairs. It needed to be someone English. But where would I find anybody on a Saturday morning? I walked out into the street, still struggling to control myself, and thought that there must be someone from England round here whom I can just go up to and tell. After about two or three minutes looking this way and that, I caught sight of this man standing in front of a shop window and looking in at the shoes. He just looked English, so I went up to him and told him that something wonderful had just happened and I needed to tell somebody. We’ve stayed friends, and in touch, ever since.’

It is way beyond my powers of description to catch David’s performance of his naïve self bursting with barely suppressed excitement, the way he accosted Jimmy, Jimmy’s response, and their subsequent animated conversation and retiring to a bar to celebrate. But I can say it had all of us rocking with laughter along with a need to pinch ourselves and remind us that this was the author of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold as well as the unforgettable Karla trilogy – all of which I had actually read, without the author’s real name sticking in my mind.

Over the course of dinner, David kept the guests entertained with anecdotes both intriguing and hair-raising, related to the work on television and film versions of his novels, including one involving Klaus Kinski, which must unfortunately not grace the pages of this journal.

As we drove back to where we were staying, I had a typical case of l’esprit de l’escalier when it occurred to me that I should have wondered aloud to David Cornwell whether he would agree that his Secret Service training in spotting likely collaborators, targets for turning, moles, etc., probably led him to focus on a congenial figure who would be willing to listen to his tale of a young author’s first steps to fame. On the other hand … but, anyway, such thoughts were immediately banished by the cab driver’s slamming on the brakes after my reply to his question concerning our destination.

The request ‘St. James’ Palace, please’ brought both the cab and my thoughts to a sudden halt. ‘You can’t go there,’ he declared emphatically. ‘That’s where the royal family lives.’

Obviously, colonials shouldn’t imagine they could just roll up at such an address. But we could, and did – though that’s another story.

This article, one of a series of ABR commentaries addressing cultural and political subjects, was funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments powered by CComment