- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Ugliness and beauty

- Article Subtitle: Karen Wyld’s poignant new novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Set in colonial Australia in the 1960s and 1970s, Karen Wyld’s new novel Where the Fruit Falls examines the depths of Black matriarchal fortitude over four generations. Across the continent, Black resistance simmers. First Nations people navigate continued genocide and displacement, with families torn apart by the state. Where the Fruit Falls focuses on the residual effects and implications of such realities, though it presents a quieter narrative: one of apple trees, wise Aunties, guiding grandmothers, and settlers both malicious and kind-hearted.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

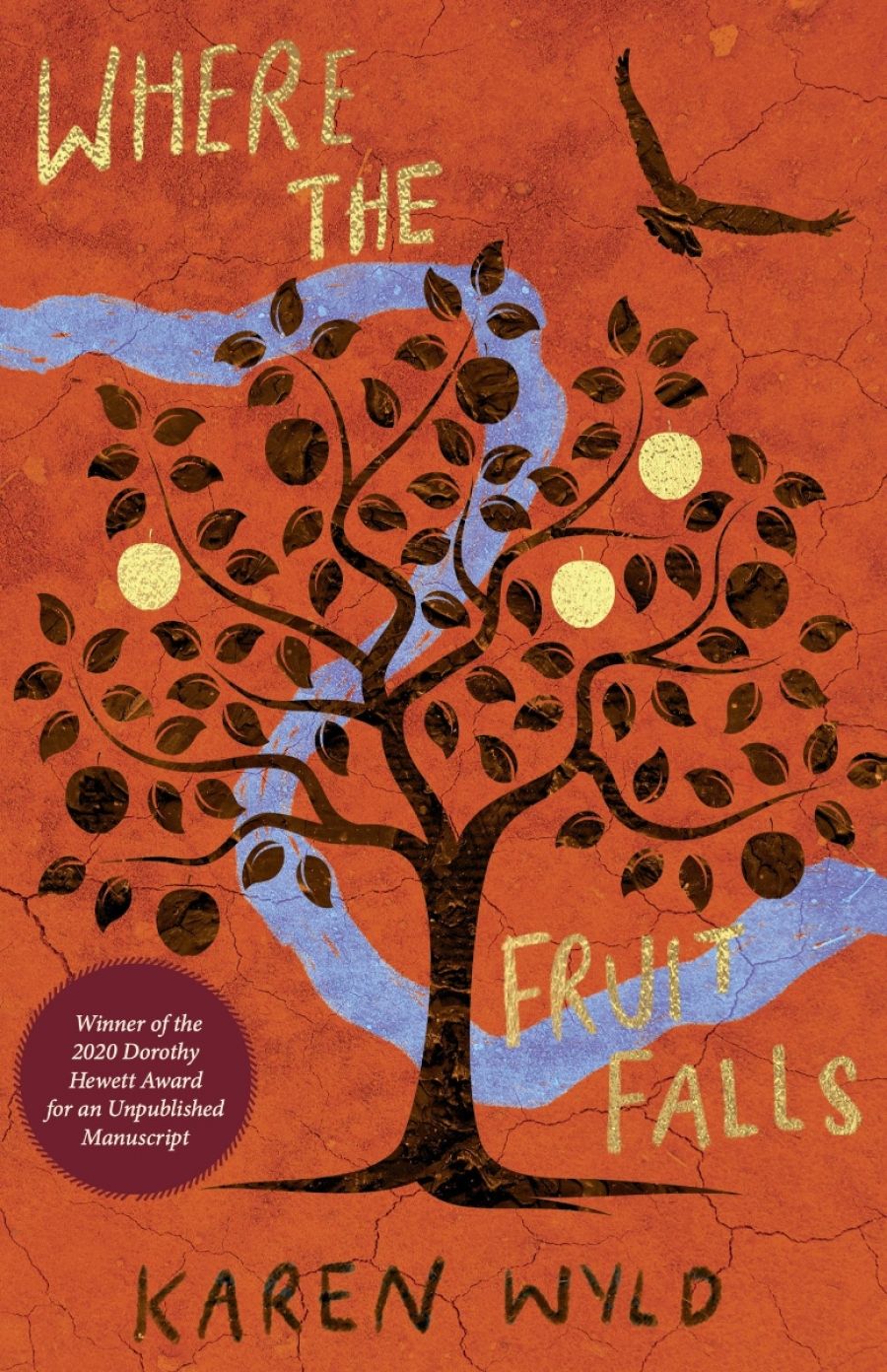

- Book 1 Title: Where the Fruit Falls

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $27.99 pb, 344 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/KeK9Xn

There was no substantial change. No truth-telling. They’d simply changed the flavour of that sugary snake oil they kept peddling. Those who has seen this all before prophesied a new stream of putrid winds from those concrete cities built on the coasts. That wind was headed towards this nowhere town on the gibber plains, to blow on the existing embers of hate. They knew it was best to be somewhere else, by the time that wind arrived.

Despite the changes that the 1967 referendum promised, First Nations people kept moving and kept hiding. Police were still regularly called by nosy onlookers, and children were (still are) removed by government intervention. Works such as Wyld’s and Birch’s transcend the history and scholarship told predominantly through a white lens, offering us unyielding storytelling free from guile – stories that relate truths and portraits as harrowing as they are beautiful, both magical and real.

Wyld’s intrinsic love for and knowledge of Country comes through in generous detail which some readers may overlook if not careful. The importance of listening – of really hearing Country and the guidance of those older and wiser – are central themes of the story. ‘This is a bad place, Maggie declared. Can’t you hear the screams?’

Maggie’s mother, protagonist Brigid Devlin, is not always listening. She’s stubborn and distracted, fixated on finding her long-lost love. She packs up her few belongings, infant twins in tow (Maggie and Victoria). They walk and then walk some more. As time goes by, Brigid’s heart grows heavier but the yearning she holds for her estranged lover has no bounds. It’s a big love; the kind typically found in fiction or tales passed down from another time. A love you’d wait (or walk) years for. As Brigid and her daughters travel, their ancestors are always watching and making their presence known through dreamlike dialogue or the antics of a cheeky Willie Wagtail. As readers, we are not privy to where her old people are trying to guide Brigid to; instead, we are taken on the journey with her.

Wyld’s development of characters and their backstories is comprehensive. Thematic throughout is the importance of knowing where one comes from and whom we return to – as is passing down these practices ‘proper ways’. Wyld’s dialogue is punchy, natural, expressive, devoid of contrivance. Readers bear witness to each character’s mannerisms, be it the hot flush of embarrassment, the twin’s excited squeals, or Brigid’s ‘deepened’ frown. Rarely is nuance withheld, with the text drawing out the ugliness and beauty in finding oneself when coming of age, albeit in a new and violent colony.

Wyld’s infant and child characters feel both familiar and authentic. The unique dynamic between the twins is depicted convincingly as is their ability to confound baffled onlookers eager to identify them by their individual features.

There is a quaint, childlike charm throughout, which Wyld skilfully crafts. ‘Townsfolk’ are contended with, beds are made up, and quiet rituals are conducted. Hearty rations are warmed and shared across humble kitchen tables. Where the Fruit Falls evokes an architectural element, illustrating natural spaces and dwellings through moving imagery that foregrounds the way such spaces are utilised and embodied by the characters. Omer, a hospitable settler, reflects on his journey to Australia where he sought solitude among the emergency rowboats, ‘they had tarps on top of them, to prevent them filling up with rain and sea water, which made them perfect nests for hiding’.

Wyld’s ability to evoke a sensory experience is noteworthy. She writes tenderly about the omniscient Dreaming; the crisp sound of fire; the juices of freshly cooked roo trickling down hungry chins. The grounding of ‘hot red dirt country’ and the secrets it holds concealed, accounts of massacres and continual ruin inflicted on First Nations people. The wild vibration of an ocean once thought to be mythical, only to be undeniably seen and heard, as recounted by fellow roamers met along the way. Where the Fruit Falls is a heartening text, both charming and poignant – a thoughtful tale that feels like a warm hug from a beloved grandmother.

Comments powered by CComment