- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘A fraught endeavour’

- Article Subtitle: Internationalism and the Tasman world

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In July 1894, a year after New Zealand women had gained the national right to vote (the first in the world to do so), their spokesperson Kate Sheppard prepared to address a suffrage rally in London, alongside Sir John Hall, the parliamentary sponsor of the New Zealand suffrage campaign. They took the stage in the vast Queen’s Hall at Westminster to report on their historic fourteen-year struggle. In an age when oratorical skill defined public authority, Sheppard was, unfortunately, not a forceful speaker. She was evidently ill at ease on the platform and her voice ‘scarcely audible’, as historian James Keating reports in Distant Sisters, his meticulous account of Australasian women’s international activism in support of women’s suffrage between 1880 and 1914.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

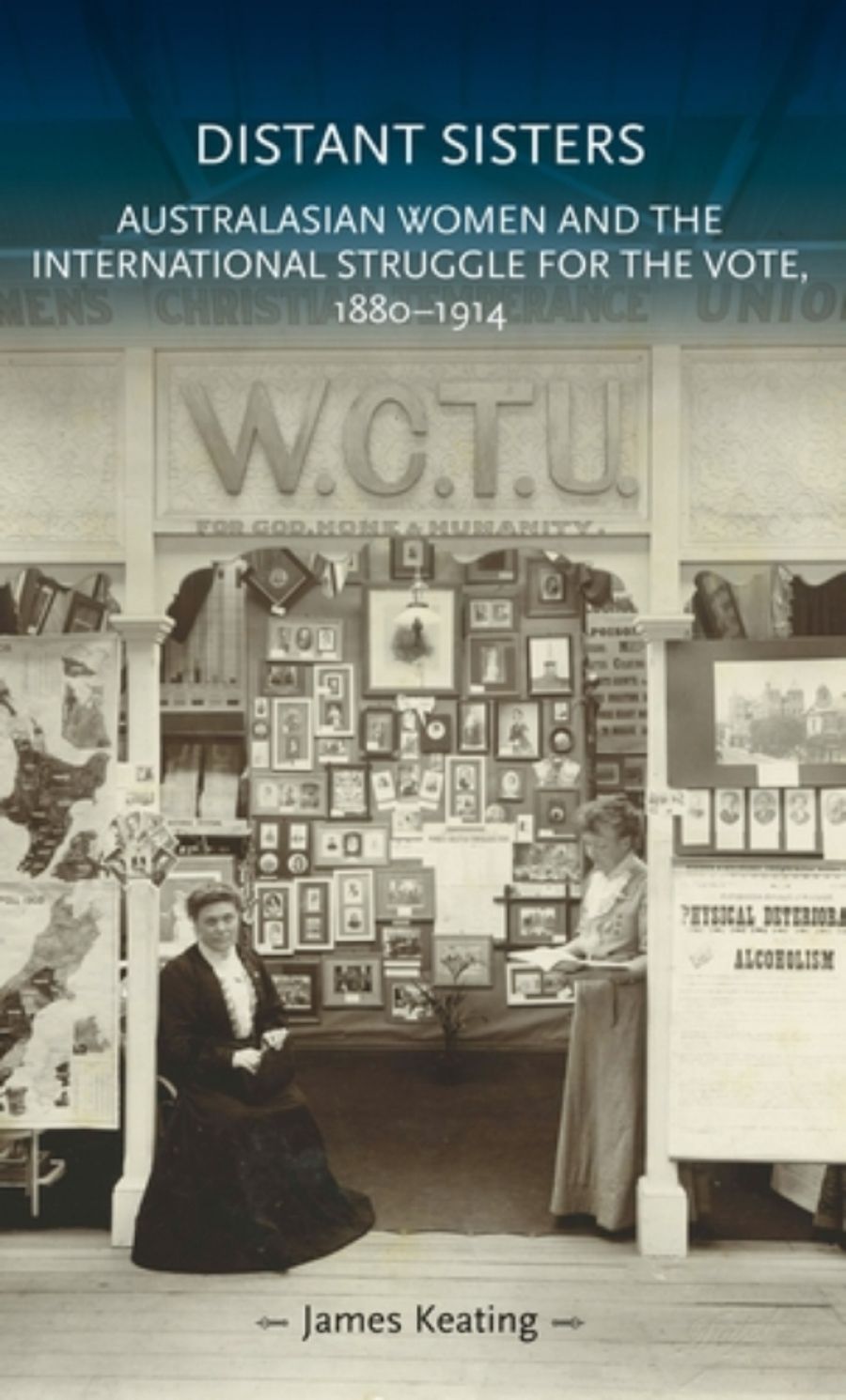

- Book 1 Title: Distant Sisters

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australasian women and the international struggle for the vote, 1880–1914

- Book 1 Biblio: Manchester University Press, £80 hb, 269 pp

Keating, a New Zealand historian now working in Sydney, rightly insists that the ‘Australasian’ story of international suffrage should cast aside ‘national blinkers’ and eschew Australian narcissism to address the history of the larger ‘Tasman world’. In this ‘regional’ analysis of women’s cross-border interactions and transnational activism, he offers case studies of suffrage internationalism from the three self-governing colonies of New Zealand, New South Wales, and South Australia. Rejecting the celebratory tone of recent nationalist historiography that lauded Australian suffragists’ international success as exemplars of freedom, Keating’s account emphasises the ‘limits’ of Australasians’ pre-war internationalism, which he casts as ‘a fraught and frustrating endeavor’, a project in which antipodeans played but ‘a circumscribed role’.

Kate W. Sheppard, c.1905 (H.H. Clifford/Canterbury Museum)

Kate W. Sheppard, c.1905 (H.H. Clifford/Canterbury Museum)

In an account centred on the three colonies, the experiences of Victorian trailblazer Vida Goldstein and Tasmanian globetrotter Emily Dobson are necessarily relegated to the margins. In a determinedly demythologising narrative, the oratorical limits of New Zealand representative Kate Sheppard come to symbolise the larger ‘failure’ of Australasian women’s internationalism. While South Australian Catherine Helen Spence is recognised as the quintessential ‘political tourist’, addressing more than one hundred audiences during her triumphal lecture tour across North America and the United Kingdom, her success as an influential policy reformer seems less instructive for Keating than Sheppard’s public breakdowns, which led her to ‘withdraw from the role of travelling propagandist and become a wistful observer at the margins of the international women’s movement’.

According to Keating, Australasian women relinquished their place on the international stage almost as soon as they had taken it up. Colonial accents were no longer to be heard at overseas gatherings. By 1914, the ‘antipodean suffragists’ moment in the sun had passed’. Partly this was a result of the tyranny of distance – and associated costs of travel – for suffragist sisters, who lived so far from Europe and the United States and (unless independently wealthy) needed to raise money to pay for long sea and rail voyages. Australasian men who voyaged to imperial and international conferences and appointments usually represented governments, which paid for their travel.

But there were other barriers to women’s participation and office-bearing in new international organisations such as the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance. In Australia, in 1901, the separate colonies federated into the new Commonwealth of Australia. Colonial suffrage leaders, beset by intercolonial rivalries and jealousies, found it difficult to build a new federal women’s organisation that might officially nominate national representatives to international conferences. As many historians have pointed out, burgeoning internationalism paradoxically rested on strengthened nation-states. Not until the formation of the Australian Federation of Women Voters in 1921 did Australia gain its first national women’s organisation that could legitimately appoint representatives to international meetings.

The second reason enfranchised Australasian women were less interested in pursuing suffrage rights at the international level was that their own early political empowerment focused their minds on what could be achieved with the power of the ballot at home. In Australia, voting women were intent on building a woman-friendly commonwealth, fashioning a new kind of welfare state that would put the interests of mothers and children first. Their singular achievement as maternal citizens – establishing women’s hospitals, children’s courts, mothers’ pensions, and maternity allowances, together with the appointment of women doctors, magistrates, prison matrons, and factory inspectors – soon won them an international reputation for progressive reform. International reports often cited Australasian legislation and precedent. International visitors duly crossed the Pacific to see what voting women could do.

Maud Wood Park, for example, the inaugural president of the National League of Women Voters in the United States, travelled to Melbourne and Sydney in 1909 on a research trip to find out what enfranchised women did with the vote, how they organised and defined their goals. Did they join existing men’s political parties or maintain their political independence? Park’s visit rested on international networks. She had met Goldstein in Boston when the Australian lectured there in 1902. At Goldstein’s invitation, Park addressed women voters in Melbourne and interviewed male and female political leaders, including Labor leader Andrew Fisher. In Sydney, she met Rose Scott and researched different women’s political platforms. While American and British women still campaigned for suffrage, Australian women were busy engaged in the actual practice of citizenship. After her extensive research, Park reported, she was able to gain ‘a pretty definite idea of what women’s causes were’, fatefully concluding that enfranchised women should steer clear of male political parties to achieve their distinctive goals.

In writing a narrative of the failure of Australasian women’s internationalism, Keating offers a rather narrow definition of internationalist networking, engagement, and achievement. Rather than assess the international impact of distinctive Australasian ideas and innovation – their collective state experiments in maternal and child welfare reform – he concentrates on individual careers and their international limits. More research remains to be done to chart the international circulation, development, and interaction of feminist ideas and policies in the early twentieth century, to delineate the international history of Australasian feminist thought and the dynamic interplay between national policies and international reception. Rather than cast paths not taken as a history of failure, it might be more fruitful to think further about the meaning and significance of the different paths actually pursued.

James Keating is a fine historian. In his assiduous ‘multi-archival’ research, attention to historiography, and desire to say something new, he is indeed a historian’s historian. With extensive footnoting and documentation, Distant Sisters is an admirable scholarly production. The ‘Gender-in-History’ series at Manchester University Press has served the author well; it is to be hoped that the book will be available in multiple copies at all good libraries. It would be a pity if its excessive cost prevented Distant Sisters from being widely read and debated.

Comments powered by CComment