- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Language

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘When the light changes’

- Article Subtitle: Anatomising the sentence

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

In one of the indelible memories of my life, I take in a room drained of sunlight – late afternoon, early evening – and the blotchy font of a 1990s Picador paperback edition of Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient. I feel a slipping sentence: ‘In the kitchen she doesn’t pause but goes through it and climbs the stairs which are in darkness and then continues along the long hall, at the end of which is a wedge of light from an open door.’ The words move and there is movement and ‘a buckle of noise’ and ‘the first drops of rain’.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

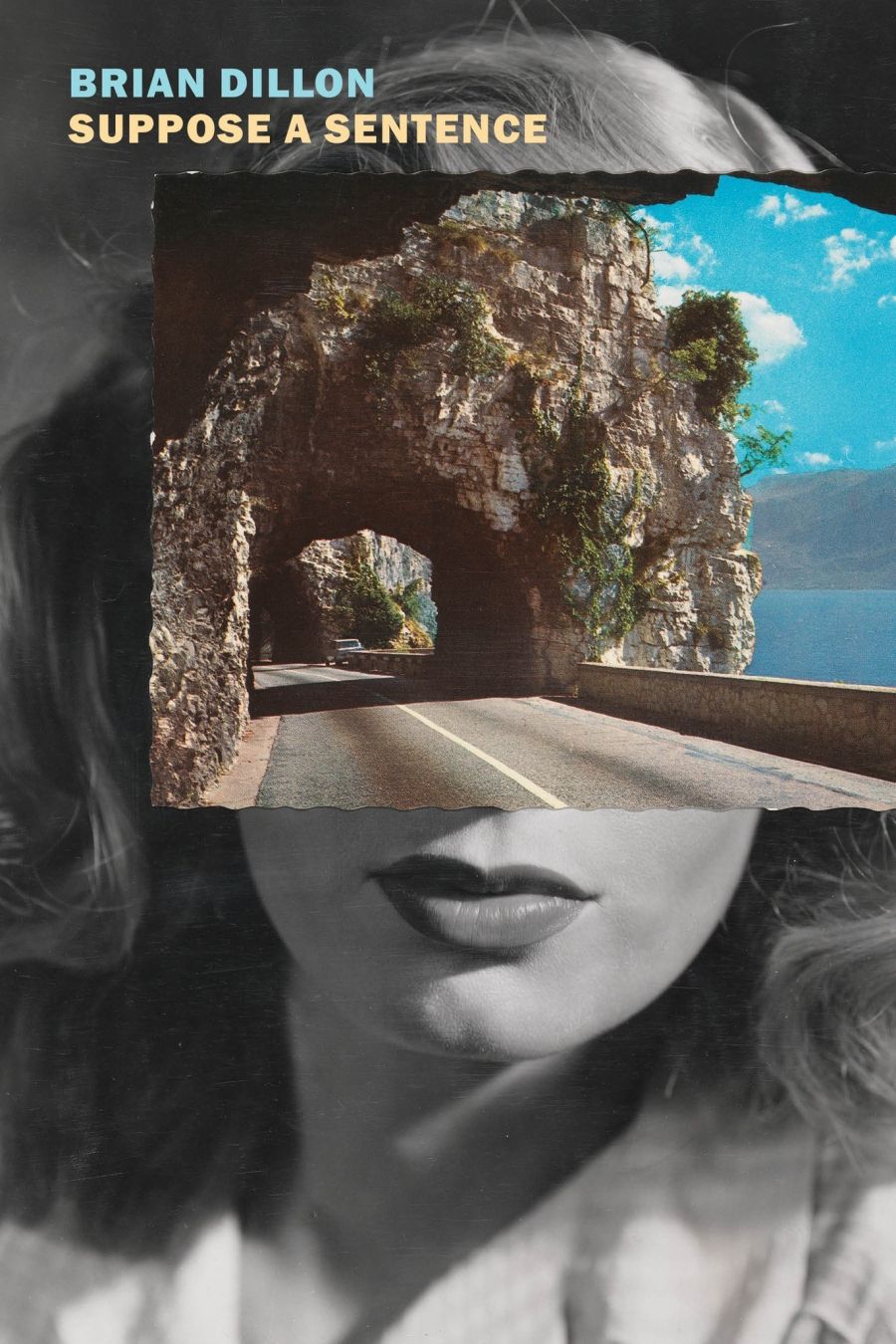

- Book 1 Title: Suppose a Sentence

- Book 1 Biblio: Fitzcarraldo Editions, £10.99 pb, 200 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/kLaaM

Several are taken from stylistic novels, others from newspaper essays (e.g. Hilary Mantel on Princess Diana), reviews of jazz (Whitney Balliett, Elizabeth Hardwick) and art (Frank O’Hara); profiles (Fleur Jaeggy on Thomas De Quincey), captions that Joan Didion wrote in the 1960s for Vogue – how they sparkle and wink; and, in the case of Anne Boyer’s Garments Against Women, ‘a collection of poems, an essay or essays, a memoir and (or) an argument’.

In Suppose a Sentence, you’ll hear the ornate humming of John Ruskin, but, as Dillon notes, there’s no Proust, Joyce, Melville, or Gass. He’s chosen sentences with aesthetic flourishes, but they’re not without ungainliness: ‘I wanted sentences that would open under my gaze, not preserve or project their perfection.’ The following passage is revelatory; it comes when Dillon is trying to pin down one of De Quincey’s ‘gorged and engorged’, ‘high-flown’ sentences:

It is not really a matter of beauty or elegance, though a strangely lucid control of the sentence might be the first thing one admires in these writers. Something else, a grand engaging awkwardness, is soon felt; the sentence does not lose its way exactly, but somewhere forgets itself, and the reader slips with it, smiling.

Some examples, two shorter ones in full. Here is James Baldwin’s sly and polite (and entirely justified) jazz-infused take-down of Norman Mailer: ‘They thought he was a real sweet ofay cat, but a little frantic.’ Via Dillon’s ‘brief etymological excursion’, we understand that ‘ofay’ (originally au fait) is essentially the opposite of hip, and that ‘frantic’ is the opposite of cool.

Speaking of jazz, here’s another short one, this time from New Yorker critic Whitney Balliett; let’s just enjoy it: ‘Parker’s medium-tempo blues had a glittering, monolithic quality, and his fast blues were multiplications of his slow blues.’ Dillon writes about this sentence’s economy and ‘the solid paired adjectives, for a start’. Marvel at the sax-gold nausea in its tail.

It’s fascinating to hear some sentences squeak or sharpen. The sublime, it seems, has its ‘engaging awkwardness’. Some of De Quincy’s beauty, Dillon writes, is ‘stutteringly awful’, and despite an ‘exquisitely shaped adventure’ in a long swervy one by Virginia Woolf, her sentence ‘finally fails to hold itself together’. Claire-Louise Bennett’s stories are ‘full of such ordinary, even pitiful, words and phrases’, but Dillon follows by praising his chosen sentence: ‘what risks it takes: with ordinary unguessable future that is a summer party; with its repetitions of sound and sense, strung out like fairy lights (if one fails the whole thing’s a dud)’.

An ‘inelegant’ sentence by artist Robert Smithson is nonetheless a ‘container for the rubble of meaning’ and the consequence of a sculptor treating language like matter. The result is Smithson’s strange and magnificent phrase: ‘Noon-day sun cinemaised the site’.

Dillon’s project, his tone, is earnest. There are straight-faced lines like ‘Something strange, dislocating, happens with the sentence’s medial colon’ and ‘But wait, it’s all much more complicated. Because even before we get to the semicolon … ’Ruskin’s semi-colon acts like a hinge, balancing an entire paragraph that ascends and descends, and Dillon shows us how his busy, unstable descriptions of sky and fields and fog stand in for the cinematic age that would follow. What did our sentences lose to cinema?

It’s no surprise to read that Roland Barthes is ‘the patron saint’ of Dillon’s sentences. The chosen Barthes entanglement, about an experience of eating Japanese food, is a delicacy, as is Dillon’s response: ‘A pair of chopsticks is like an inked brush or pen: it points, discerns, invents and describes.’ Beautifully, Dillon finishes the essay by writing that it ‘has now grown light enough for me to let it go’, as if he had held the writing in said chopsticks.

This is an artfully assembled book. As it opens, we step through a smoke ring – to a lexical plane – by examining a lesser-known variant of Hamlet’s final utterance: ‘O, o, o, o.’ Dillon contemplates ‘O’ as a stand-in for: a full stop, the globe theatre, a discrete cry, a sigh, the ‘apotheosis of zero’, and ‘the vocal expression, precisely, of silence’.

Suppose a Sentence, a title containing its own aural ‘O’, ends with a story from Rousseau retold by Anne Boyer, around that same letter. I won’t spoil it, but Boyer speculates about ‘O’ as ‘the proximate shape of the fountain’. Suppose a sentence was the shape of a fountain.

Comments powered by CComment