- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Once, twice, thrice

- Article Subtitle: A year of lamentation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A detailed timeline prefaces Fire Flood Plague. Stretching from September 2019 to September 2020, it charts events so momentous that Christos Tsiolkas describes them as being ‘imbued with an atavistic, Biblical solemnity’. Sophie Cunningham, the book’s editor, notes in her introduction that many of the contributors (herself included) have found themselves drafting their essays ‘once, twice, thrice, as we’ve progressed from bushfire and smoke-choked skies, to the early days of the pandemic … and into the exhaustion of what is becoming a marathon’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

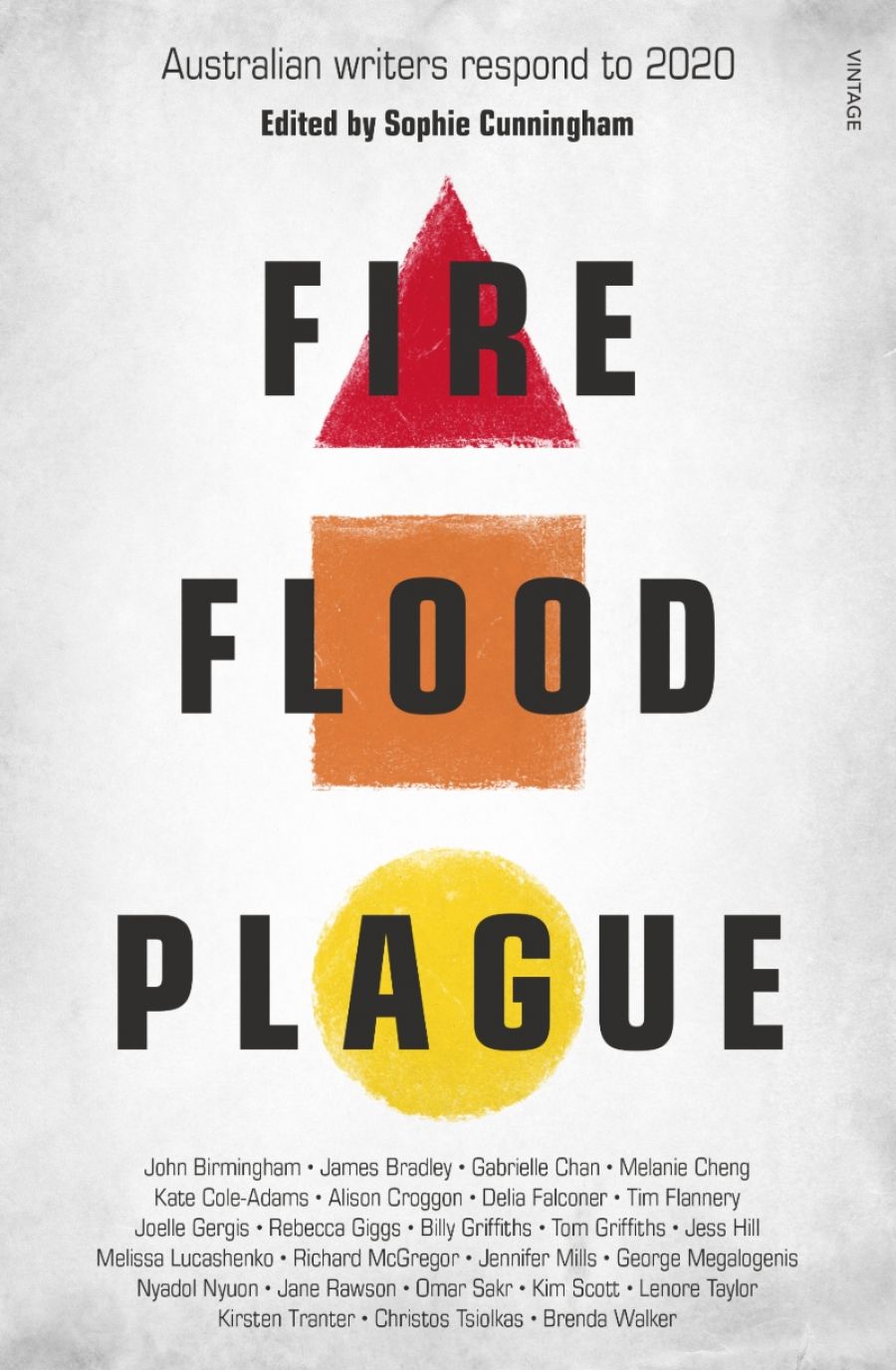

- Book 1 Title: Fire Flood Plague

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian writers respond to 2020

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage Books, $29.99 pb, 255 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/00xJJ

The real achievement of Fire Flood Plague is the way it zooms out from what Jess Hill calls ‘the hour-to-hour dramas that consume us’. While our experience of 2020 may have been one of contraction and containment (cocooned spaces, border closures), much of the writing here is expansive in scope. Billy Griffiths wonders how the current moment might shift our historical imagination. Might we, for instance, better grasp the impact of the 1789 smallpox epidemic, which he describes as the ‘single greatest demographic catastrophe in Australian history’? Might we fathom the deep wisdom of traditional fire-management practices?

Jess Hill’s essay is similarly capacious. While her immediate impulse is to flee from the fires, ultimately she realises that there is no escape. ‘“It” won’t ever be over, because “it” is not just one thing’: the fires, the virus, domestic violence, and racism stem from the same diseased roots. Hill argues that Australia needs to have an ‘honest reckoning with our colonial past and present’, and looks to Indigenous cultures as models of balance, sustainability, and interdependence. Jennifer Mills uses breath as a lens through which to ponder our ‘moral entanglement’: ‘the question of who breathes, and who suffocates’, she writes, ‘is a question of who deserves to live … of who is part of a community of care … a question that will only become more urgent as the climate crisis develops’.

More than one writer notes that the pandemic was politically convenient for the Australian government, postponing action on climate change that the fires should have prompted. Along with his fellow-scientists, Tim Flannery is unequivocal that we must act to avert the ‘looming disaster’ of climate change: ‘in COVID-19 terms, we are in mid-March’. Nevertheless, he sees cause for optimism in Australia’s swift and effective pandemic response: Australians have proof, now, that their government ‘can do extraordinary things to protect them’.

Lenore Taylor echoes this sentiment: for her, the evidence-based governing that has characterised the Covid era might help us to ‘nurse civic debate back to something constructive’ in the context of climate policy. Several writers point out that the megafires and coronavirus are not unrelated: Tom Griffiths sees both as symptomatic of the ‘acceleration and concentration of the impact of humans on nature’; Kim Scott mourns the damage done to our planet’s ‘natural, interlocking systems’. Some see 2020 as exacerbating existing inequalities and urge us to remember that, for many, the experience of living under threat is nothing new. Melissa Lucashenko, responding to (non-Indigenous) Australians’ complaints about being ‘locked up’, says: ‘Cry me a river, bitches.’

Other essays contain more introspective moments. Delia Falconer expresses relief in a ‘world temporarily stilled’, and some of the collection’s most powerful essays might serve to still the reader’s thinking. Kate Cole-Adams writes movingly of the much-maligned Zoom technology, its constraints intensifying the quality of her attention, so that she rekindles an old friendship that reveals itself to be ‘unmarred by time, space, the passage of grief’. Rebecca Giggs sees ‘a fable of nature’s resurgence’ in people’s flourishing interest in birdlife and birdsong. Faced with shapeless days, we hunger for ‘visible propulsions of time in nature’; we badly need ‘proof of some other, overlooked world nestled into the human one’.

James Bradley parallels his own personal grief over his mother’s death with our wider sense of loss and fragility: ‘like all of us, I feel undone, unmade … and the world I know is gone’. A hospitalised Omar Sakr is awestruck by the ‘resolute care’ of his nurses. Tonally, Sakr’s complex essay is reflective of the collection’s mixed notes of hope and hopelessness, rage and reverence. He laments our complacency but glimpses sacredness in the work of the nurses who tend to him, and redemption in his own act of writing.

Fire Flood Plague unites poets, scientists, novelists, journalists, and historians, thus dismantling the barriers we often erect between science and humanities. Part of the delight of reading this collection lies in viewing the interconnectedness of systems we tend to regard as distinct: weather systems, political systems, ethical systems. Within individual essays, too, this collapsing of borders is evident: between past and future; intellect and imagination; reason and emotion. Climate scientist Joëlle Gergis, for instance, frames emotion as a catalyst for real change. For her, ‘despair, grief, anger, frustration’ are rational responses to the ‘existential threat of planetary proportions’. ‘Until we are prepared to be moved by the tragic ways we treat the planet and each other, our behaviour will never change’.

Comments powered by CComment