- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Language

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Camouflaging the cussword

- Article Subtitle: Exploring Australian slang

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Bad language’ comes in many forms, but, as the title suggests, the focus of Amanda Laugesen’s new book is on slang and, in particular, swear words. She documents Australia’s long and often troubled love affair with this language, dividing the history into four parts: the earliest English-speaking settlements of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; the period of Federation and World War I; the heart of the twentieth century; and the ‘bad language landscape’ of modern Australia. These four time periods highlight Indigenous stories as well as migrant contributions to the diverse swearing vocabulary of Australia.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

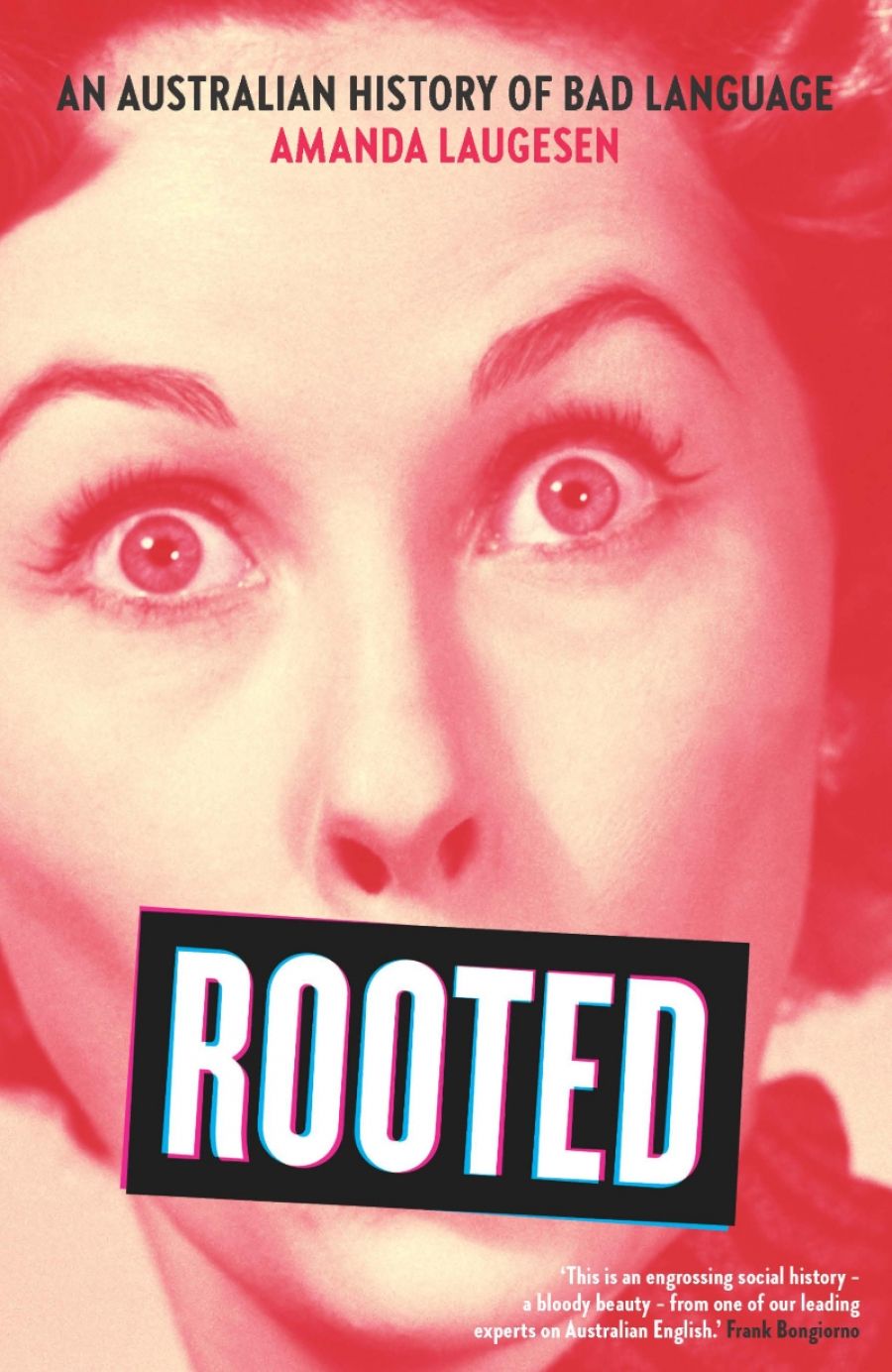

- Book 1 Title: Rooted

- Book 1 Subtitle: An Australian history of bad language

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $32.99 pb, 320 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/N1Qxb

Swear words are rooted deeply in human neural anatomy, but what goes to clothe the expression is the socio-cultural setting, in particular the taboos of the time. As Laugesen describes, when blasphemous and religiously profane language was no longer considered offensive (at least by most speakers), what filled the gap were physically and sexually based modes of expression. Their potency has now also well and truly diminished. These days, such swear words are frequently encountered, and widely accepted, in the public arena. Lashings of obscenities became the earmark of celebrated chef Gordon Ramsay, so much so that one of his television cooking series was called The F-Word. Laugesen reports how a single episode of the earlier Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares featured some version of the word ‘fuck’ on eighty occasions over a forty-minute period. (I’ve always felt that Ramsay would do well to heed the warning once issued by Vogue food editor Joan Campbell: ‘Nothing is more deadening to the taste buds than a flavour repeated too often.’)

As linguist Anna Wierzbicka has described in her exploration of the so-called ‘Great Australian adjective’ bloody, ‘change is not inconsistent with continuity’. Laws against sexual obscenity have been relaxed, but ‘ist’ taboos have stepped up to make racist, sexist, ageist, etc. language not only contextually offensive but legally so. Laugesen describes the celebrated 2017 case Danny Lim vs. Regina: in reference to the then prime minister, Tony Abbott, Lim had worn a sign saying ‘Peace Smile. People Can Change. Tony, You C∀N’T.’ Judge Scotting concluded the language was in poor taste but not necessarily offensive. It would have been a different outcome had Lim’s protest been deemed an act of public racism.

Interestingly, however, none of the many newspaper articles reporting this case quoted the offensive expression in full. Courts may well be ruling that cunt is no longer obscene, but the word maintains its ‘shock-and-horror capacity’ in the print media. Speakers will of course have no trouble recognising c—t, c**t, or even c*!@. The inbuilt redundancy of English spelling means people can usually read words when vowels are left out or letters are transposed; in fact, symbols and unconventional spellings seem to highlight the obscenity rather than obscure it. These expressions are attention-grabbers, a fact not lost on the designer label FCUK. This is a strategy that provides much potential for language play, more advertisement than camouflage (as Lim’s jocular sandwich-board pun shows).

Indeed, Laugesen’s account celebrates the creativity around the camouflage of cusswords. When bloody fell from grace, its unmentionableness triggered a flourishing of euphemistic remodellings such as the expletives blimey, blast, blow, and the epithets blessed, bleeding, blooming, and so on. Even blank as an omnibus euphemism and the game Blankety Blank obviously play on bl–, now a kind of nudge-nudge, wink-wink consonant cluster. Linguistic ‘fig leaves’ express the same emotions as full-blown obscenities and nicely illustrate the sort of human double-think that accompanies so much of our linguistic behaviour, especially in the area of euphemism and taboo.

The message of Rooted is that swearing is a particularly rich area of creativity engaged in by ordinary Australians, and one that it is socially and emotionally indispensable. It’s a message backed up by recent linguistic research. Cusswords are vital parts of our linguistic repertoires that help us mitigate stress, cope with pain, increase strength and endurance, and bond with friends and colleagues – it’s not for nothing that they are described as ‘strong language’. But Laugesen’s book also never lets us forget there is a less heroic side to this language. Swear words provide that bonus layer of emotional intensity and added capacity to offend. It’s difficult to imagine that there is any plus side to this linguistic behaviour, though it might be a comfort to know that abuse is the least usual type of swearing. In Laugesen’s account, social swearing features large. In fact, many different studies have shown this – swear words are usually solidarity expressions, a part of verbal cuddling or friendly banter.

Swearing in Australia has always been characterised by a mix of exuberance and restraint. Laugesen’s account of literary censorship of the mid-twentieth century describes Australia as ‘one the strongest censors in the Western world’. It’s worth pointing out here that our strong attachment to the vernacular is also accompanied by a thriving linguistic complaint tradition, one that even exceeds what has been observed in other major English-speaking nations. Australians place a high value on larrikinism. At the same time, Australia is a society that is exceedingly rule-governed. As historian John Hirst once pointed out, at football matches Australian spectators yell abuse at umpires and players and then, at half time, obediently file outside to have a smoke.

Swearing is an area of vocabulary that most people find fascinating, and yet it’s one that has received comparatively little attention. An extensive historical account of Australia’s colourful vernacular is long overdue. Historian and lexicographer Amanda Laugesen is exactly the right person to write this story, and she has produced a rollicking good read.

Comments powered by CComment