- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘A world of wounds’

- Article Subtitle: Living with a changing climate

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Last month I was volunteering with a group of botanists surveying coastal heathland in the Tarkine Forest Reserve in North-West Tasmania when one of them cried out, ‘Orchid!’ We all rushed over excitedly, our phones and pocket magnifiers at the ready. It was a Green-comb Spider-orchid (Caladenia dilatata), with long, delicate-green limbs and a reddish-purply face, hovering like a ballet dancer in mid-leap. The first thing that astonished me was how tiny it was – no bigger than a human eye – and then, how solitary. Like many orchids, C. dilatata uses sexual deception to mimic the shape of a female wasp; when males attempt to mate with it, they accidentally collect pollen, fertilising the next orchid they visit. Millions of seeds scatter on the wind, but only a few will land on a sunny patch of soil where the correct mycorrhizal fungus is present for it to germinate.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

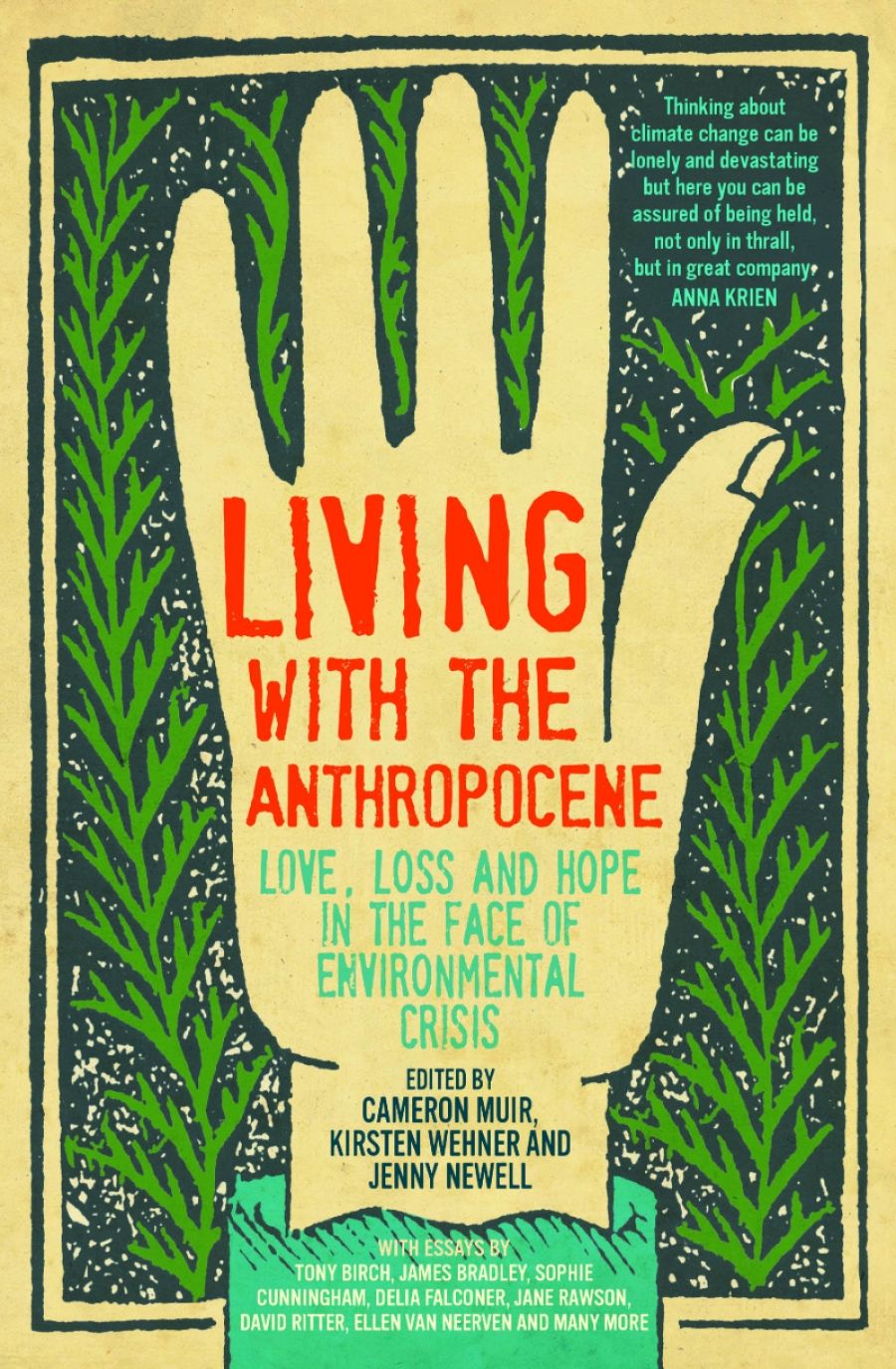

- Book 1 Title: Living with the Anthropocene

- Book 1 Subtitle: Love, loss and hope in the face of the environmental crisis

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 384 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/VoZna

In Living with the Anthropocene, editors Cameron Muir, Kirsten Wehner, and Jenny Newell argue that ‘people now shape the world everywhere’, yet we have lost sight of how, like the Spider-orchid, ‘our own wellbeing is completely tied up with that of wider ecological communities’. Industrial farming methods and mechanised systems of mass production have severed our ties to the natural world, ushering in not only the Anthropocene (the ‘Age of Humans’), but potentially, as biologist E.O. Wilson warns, the Eremocene (the ‘Age of Loneliness’). Given the vast impersonal forces of capitalism, consumerism, and globalisation at work, what might writers offer that international committees of scientists and UN policymakers cannot?

‘You’re not alone’ are the first words of this essay collection, which brings together a diverse range of Australian voices – ‘historians, ecologists, walkers, gardeners, artists, activists and students’ – to bear witness to our current situation and to offer imaginative responses and alternative narratives to it. The collection has a therapeutic as well as thematic structure, beginning with grief, despair, and anger. In the first two chapters, ‘Facing the Storm’ and ‘Tearing Away’, Tony Birch reflects movingly on the intersection of personal, cultural, and environmental loss, while climate scientist Joëlle Gergis describes giving into ‘volcanically explosive rage’ in the face of global political inaction. Jane Rawson writes about fleeing Melbourne for the supposed climate refuge of rural Tasmania, only to find herself surrounded by bushfires. Meanwhile, Jo Chandler follows scientists into Tasmania’s Central Plateau in search of endangered pencil pines and sphagnum peat, the loss of which would be ‘akin to losing the thylacine’. Yet the scientists around her are strangely calm. ‘Life is spectacularly resilient,’ Professor David Bowman reassures her. In ecological terms, death is never final. It is merely a threshold for new transformation.

In ‘Seeking Vantage Points’ and ‘Holding On’, authors reflect on how we are choosing to respond to the climate emergency, and what this reveals about our cultural imagination and preparedness for change. Delia Falconer muses how, in the absence of meaningful action, many of us resort to sharing news stories of long-extinct animals emerging from melting permafrost on social media: ‘Atomised, and quasi-magical, they turn a dying world into a modern cabinet of curiosities.’ While some dissociate, others anthropomorphise. Nadia Bailey asks why so many people would take the time to send emails to a golden wych elm on the corner of Punt Road and Alexandra Avenue in Melbourne: ‘Some wrote asking for advice. Others for forgiveness ... our empathy runs towards those things that most closely resemble ourselves.’ Others take evasive action. Josh Wodak investigates a radical conservation experiment involving Biorock, a patented technology made from plastic, metal, and electricity, currently being used to create artificial reefs for endangered coral in Bali. Yet even this practical attempt to save a vulnerable ecosystem provokes a vexing moral question: ‘to what extent will humans “remake” nature in order to “save” it?’

There is no place on earth more alien to us than the ocean, as explored in ‘Treading Water’. ‘How should we grieve the unseen?’ asks John Charles Ryan, who notes that in Tasmania ‘warmer water with lower nutrient levels has precipitated a 95 per cent loss of kelp forests’, which are essential for sustaining countless species of fish, crustaceans, seabirds, and mammals. James Bradley reminds us that even a creature as ‘deeply weird’ as a cuttlefish shares more in common with us than we might think: ‘The fact a creature so utterly dissimilar to ourselves may be capable of complex cognition serves as a reminder not just of the extraordinary diversity of life on this planet, but also the degree to which we, and all of it, are connected to each other.’

The final chapters, ‘Regenerating Country’ and ‘Sharing the Story’, reimagine the future by returning to the past. Ellen van Neerven and Kate Wright draw attention to how our current environmental crisis is inextricably linked to histories of colonial violence, and how Indigenous practices of land management might offer a sustainable alternative to the mechanistic mindset of modern farming. The last word is given to David Ritter, CEO of Greenpeace Australia Pacific, who raises the possibility of redemption: ‘In the name of love, we can yet do this.’

‘One of the penalties of an ecological education,’ wrote American conservationist Aldo Leopold in the 1940s, ‘is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.’ Essays like these may not heal all wounds, but by offering new ways of understanding the challenges we face, they might help us reimagine new rules for living.

Comments powered by CComment