- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Think global, act local’

- Article Subtitle: Cathy McGowan’s colourful political memoir

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

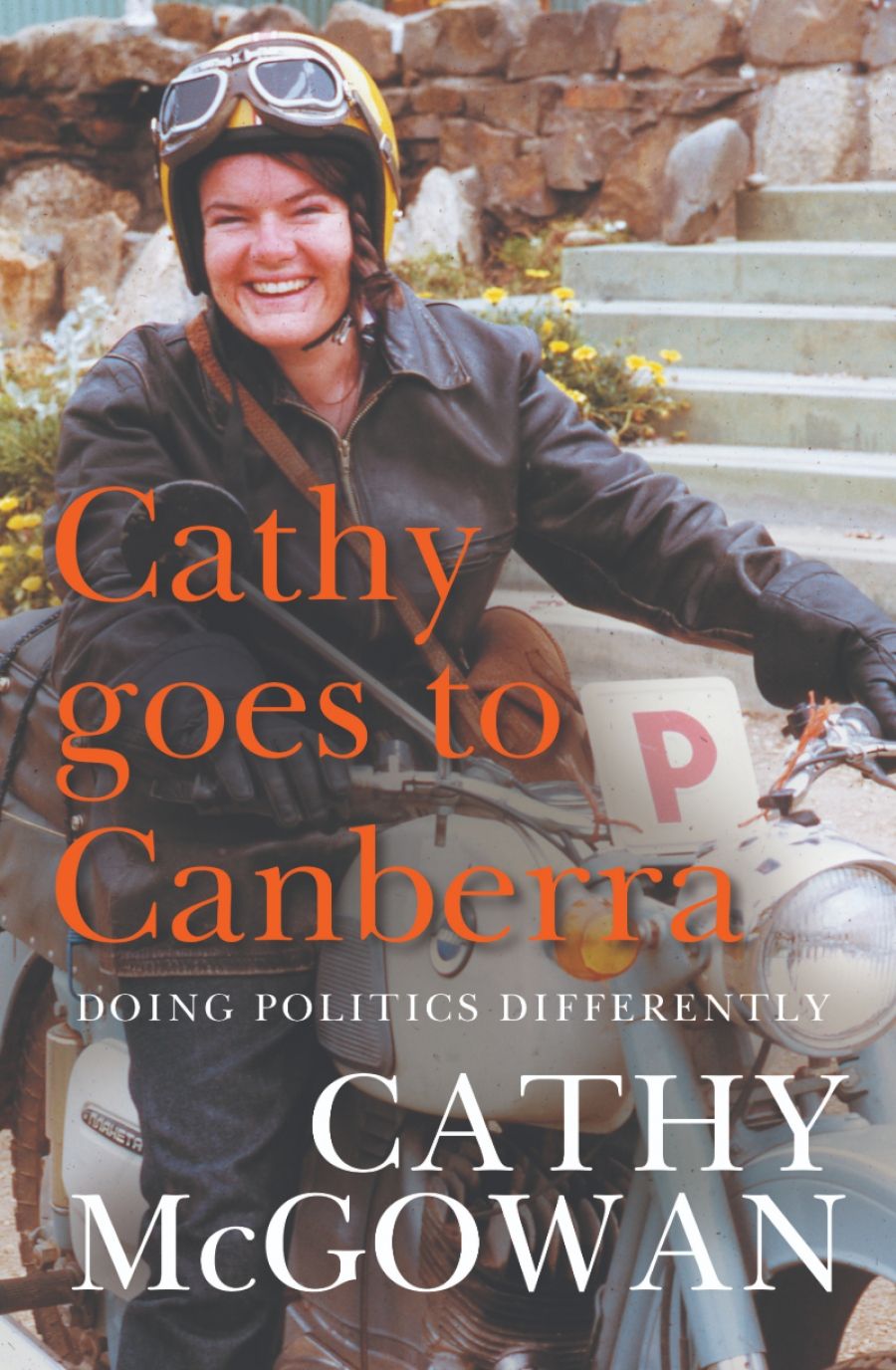

‘Orange balloons. Orange streamers. Orange shirts.’ Cathy McGowan’s memoir is saturated and literally wrapped in the colour. Cathy Goes to Canberra begins with an account of the election of her independent successor as Member for Indi, Dr Helen Haines, in May 2019 – ‘with orange everywhere’.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Cathy Goes to Canberra

- Book 1 Subtitle: Doing politics differently

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Press, $29.95 pb, 280 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/xAnX1

McGowan’s memoir is partly the story of an independent rural woman finding her way as an independent MP, and partly an impassioned tract about rescuing parliamentary democracy from major party partisans with their ‘gossip’, ‘jostling’, and ‘intrigue’. ‘I regard those people as Political with a capital “P”,’ she writes. ‘I’m lower case “p”.’

Politics, in this memoir, is so much more than a game of parliament, factions, and parties. Small-p politics begins with the local and the personal; the terse and almost violent sectarian ‘politics of the school bus’; the crowded spaces and tentative ‘alliances in the politics of a big family’ (she was one of thirteen siblings); and the gender politics of buying motorbikes and farmland as a single woman in rural Australia. Shaped by her experiences as a leading woman in agriculture, the centre of McGowan’s politics – at least in this account – is the local. ‘Think global, act local’ is the mantra.

Image from the book under review, reproduced by permission of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation – Library Sales Marco Catalano © 2019 ABC

Image from the book under review, reproduced by permission of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation – Library Sales Marco Catalano © 2019 ABC

Memoirs by independents, once rare, are an expanding subgenre of political memoir in Australia. Where others privilege high politics and completely ignore broader communal forces in their narratives, independents largely do not. British political scientist Andrew Gamble has argued that memoirs ‘are valuable sources on the inside story but often have less to say on the outside story’. By contrast, social forces and grassroots mobilisation are central to any independent’s success story, and none more so than McGowan's. She writes compellingly about the quest to turn the north-eastern Victorian electorate of Indi into a marginal battleground; this involved a groundswell of community support and mobilisation.

McGowan’s initial campaign was less concerned with the MP–voter relationship, than with strengthening democratic relationships between the electors themselves. McGowan describes the Voices for Indi movement that propelled her into parliament not as a personal powerbase but rather as a form of ‘leadership that the community had provided for itself’. Hers is a refreshing conception of politics in which the health of democracy depends on the engagement of constituents with one another. The initial phase of the movement involved what she describes as a ‘snowball model’ of generating public enthusiasm for change, followed by countless ‘kitchen table conversations’ intended to gauge community sentiment on key issues. What matters is that the community is speaking to itself, setting its own agenda.

In this memoir, the mission to find a candidate for Indi in 2013 (ultimately McGowan) is almost incidental. If there is one flaw in this otherwise superb volume, it is the coyness of McGowan’s account of her own candidacy. She writes openly about her diffidence as the candidate, but performs the role of ‘reluctant MP’ for too long. In an apparent diary extract from the weeks following her victory, she despairs, ‘I so don’t want to be a politician, really.’ On her first day in parliament, she considers hiding in the Federation Chamber for three years and then ‘disappear[ing] at the next election’. Candour is a virtue in a book like this, but timidity mitigates its empowering purpose.

If success is the product of grassroots activism, McGowan rightly examines the socio-political preconditions that facilitated the rise of Voices for Indi. She describes the ‘increasingly sensitive’ issues facing the electorate – degraded transport services, weak telecommunications coverage, declining opportunities for rural futures – and the ‘vulnerable sitting member’ Sophie Mirabella, perceived to be preoccupied with national political debates. McGowan exposes the lack of alternatives, fingering the ALP and its ‘urban’ focus, the deep-seated dislike of ‘Greenies’ in rural Australia, and especially the ‘overwhelmingly male and old’ cadre of ‘tag-alongs’ and ‘back-seat occupiers’ in the federal National Party. Voices for Indi is a natural consequence of rural communities despairing at poor representation.

McGowan’s account of her time in parliament is succinct and highly readable. She writes about the challenges of being an independent in Parliament House, the lack of information channels, pre-existing support networks and so forth. She reflects on saving local community health groups from funding cuts, repairing regional rail lines, advocating for new mobile telecommunications towers, all the while fighting against ‘awful, destructive’ higher education policies, and ‘unconscionable’ approaches to asylum seekers, and helping to beef up myopic drought-funding initiatives. She also describes some of the surprisingly strong professional relationships she forged with parliamentary colleagues such as Clive Palmer (‘I discovered we had much in common’), Christopher Pyne (‘interesting and entertaining’), and Malcolm Turnbull (‘a man of his word’).

Nonetheless, hers is a novel account of parliament, because it is the electors who constitute the lifeblood of her narrative. Among the competing demands on her time, ‘constituent work was a priority’, something that goes unmentioned in most political memoirs. Current MPs would do well to inscribe her parting motto on their office furniture: ‘Back home is where the joy of the job lies.’

Cathy Goes to Canberra is essentially a handbook for aspiring independents, with McGowan leading by example. McGowan aspires to see more independents in Australia’s parliaments. With this book, she shows them exactly how it can and ought to be done.

Comments powered by CComment