- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Swashbuckler and Son

- Article Subtitle: Tim Olsen’s matey, meaty memoir

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘A voyage round my father’, to quote the title of John Mortimer’s autobiographical play of 1963, has been a popular form of personal memoir in Britain from Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son (1907) to Michael Parkinson’s just-published Like Father, Like Son. The same form produced some of the best Australian writing in the twentieth century, with two assured classics in the case of Germaine Greer’s Daddy, We Hardly Knew You (1989) and Raimond Gaita’s Romulus, My Father (1998). The tradition has continued into the present century with – to list some of the choicest plums – Richard Freadman’s Shadow of Doubt: My father and myself (2003), Sheila Fitzpatrick’s My Father’s Daughter (2010), Jim Davidson’s A Führer for a Father (2017), and Christopher Raja’s Into the Suburbs: A migrant’s story (2020). Mothers in such sagas are far from absent, and they can emerge, though not always, as the more obviously loveable or loving figures. As signalled by most of those titles, however, mothers loom less large over the unfolding narrative. Fathers may not always know or act best, but, partly because of their often tougher, commanding mien, they become irresistibly the centre of attention.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Son of the Brush

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $34.99 pb, 485 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/WBY9X

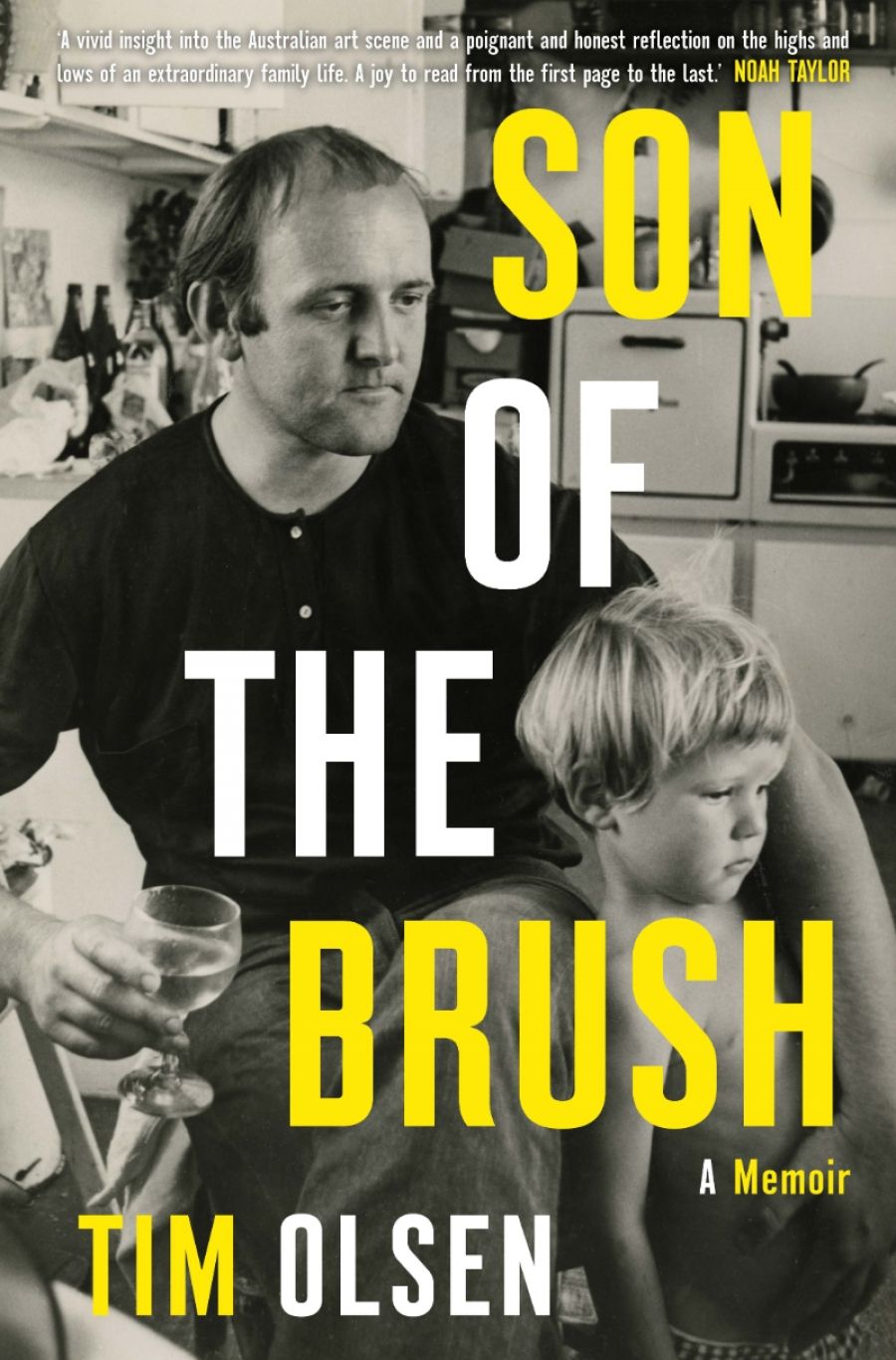

The title of Tim Olsen’s memoir, Son of the Brush, might suggest a greater degree of even-handedness. While painting was and remains the passionate vocation of his famous father, John, it was also a passion, if never a full-time profession, for his late mother, Valerie. As well as dedicating the book (in part) to her memory, he devotes several paragraphs to evoking her painstakingly exquisite and restrained landscapes and to acknowledging her creative guidance when he thought of taking up the brush himself in his earlier years. But several paragraphs don’t amount to much in a 500-page book, and the photographic image on the front cover is a more telling sign of the balance of the book’s contents than the title: a pugnacious-faced Olsen Sr standing over his young son in the kitchen of their home, with a glass of wine, not a paintbrush, in his hand – and no trace of Valerie.

John, Louise, Valerie, and Tim at Watsons Bay (photograph supplied)

John, Louise, Valerie, and Tim at Watsons Bay (photograph supplied)

Food and wine, it turns out, are as much a passion for John Olsen as his painting, and it’s one his son has eagerly shared for much of his life, though on his father’s say-so he was to give up art as a creative practice of his own and turn to art dealing, of which he has made a highly prosperous, distinguished, and fulfilling career. Anyone even remotely familiar with John Olsen’s painting, with its signature ‘spiky lines’ and bold swaths and splodges of vivid colour, will not be surprised to learn that he gave little more encouragement to Valerie’s artistic ventures, despairing of her lack of spontaneity and drive in approaching a canvas, and her fatal modesty in promoting her finished works. A fearless swashbuckler in his art, as in his life, a celebrity in his own country by his mid-thirties (and from around the time of his son’s birth), this man couldn’t help being the ‘centrifugal force’ in Tim’s family life and in much of Tim’s own career. And so again a father-figure pushes his way by force of personality to the forefront of his offspring’s memories.

The memories are far from being always good ones, though it’s remarkable how Tim’s expressions of frustration at being overshadowed, and at times neglected, by a relentlessly ambitious father are balanced by admiration of his father’s creative work and gratitude for his tough love and ruthlessly pragmatic advice. The same poise is on display in many of the pen-portraits of the collateral cast in the Olsens’ lives, most strikingly – and boldly – in the case of Donald Friend. Staying loyal to his fellow painter, whose posthumous reputation has plummeted in the light of his revelations about his sexual activities with minors in Bali, John Olsen has been adamant that ‘an artist’s work is separate from his personal life’, and not just in Friend’s case but ‘in every case’.

Representing artists in his profession as a dealer, Tim has declared that ‘separating their acts from their art’ is ‘impossible’ for him, and that he finds Friend’s sexual transgressions to be ‘unforgivable’. Yet he also can’t forget the acts of ‘kindness’ and ‘real altruism’ on Friend’s part that he personally witnessed, and he can’t accept the notion that ‘something well crafted should be admonished because of its creator’. These judicious words need to be seriously considered in our increasingly undiscriminating ‘cancel culture’, where the creative legacy of various artists who have violated contemporary moral standards is at risk of being obliterated.

You are bound to cross paths with a host of famous – and infamous – people if you’re the progeny of a star artist and also a professional dealer with the top end of the art world. So it’s for the legitimate record that we come across so many glittering names in the course of Olsen’s memoir, though on occasion there’s a lapse into pure name-dropping. Of what importance is it to be told that Tim’s young son, James, has received ‘hugs from the likes of Naomi Campbell or Elle Macpherson’? On the other hand, there’s much more ‘dropping’ of non-celebrity names that have befriended, worked for, advised – and occasionally thwarted – Olsen père and fils along the way in their respective careers. And several of these names are not just casually invoked but generously acknowledged, providing in the process some fascinating insights into the behind-the-scenes workings of the Australian and international art worlds. There’s also lots of solid, informed advice to aspiring art dealers as to how they might run an enduring – and ethical – business in such a competitive and ‘fickle’ world.

There are few factual inaccuracies that I can spot (it was Frank Muir, not Clive James, who originated that matchless description of the Sydney Opera House as ‘a nuns’ scrum’). The stylistic infelicities amount to a sprinkling, not worth listing. Delight, rather, in the endlessly cascading mots, mottos, mantras, and maxims: ‘He [the flamboyant art dealer, Barry Stern] was … the Liberace of the Sydney art scene’; ‘Art represents being in the real world much more palpably than serving a “real” job’; ‘Surveying the room [of any art gallery], I see money, sex, ego, obscurity, Botox, raw beauty and loneliness rubbing shoulders’; ‘Often my [school] lunchbox stank like a connoisseur’s napkin’; ‘The raw proto-naïve kitsch of Sidney Nolan’; ‘Buy work that speaks to you personally … Buy what you love.’

Everybody (except perhaps shonky art dealers) should love this book. It’s a matey, meaty, mighty romp.

Comments powered by CComment