- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Knotty problems

- Article Subtitle: An examination of Europe’s displaced persons

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is a book in the expansive American tradition of long, well-researched historical works on political topics with broad appeal, written in an accessible style for a popular audience. David Nasaw has not previously worked on displaced persons, but he is the author of several big biographies, most recently of political patriarch Joseph P. Kennedy.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: The Last Million

- Book 1 Subtitle: Europe’s displaced persons from World War to Cold War

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $61.99 hb, 666 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/DDLLa

That said, Nasaw has a dramatic Cold War refugee story to tell, and he tells it well. ‘Displaced persons’ was the contemporary label for the millions of people who ended up in Central Europe, far from home, after World War II. They came mainly from Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, and the question of their repatriation was the subject of an early Cold War tussle between the Western Allies (primarily the United States and Britain) on the one hand and the Soviet Union on the other. Some DPs resisted repatriation, partly in fear of punishment if they returned, and the Western Allies ended up supporting their resistance despite fierce Soviet objections. The ‘last million’ were the hard core of DPs left after mass repatriations ended in 1946. Poles constituted the largest group, but there were large groups from the Baltic states as well as from Eastern Europe, including Serbs, Croats, and Czechs. Ukrainians were well represented, too, some of them prewar Polish citizens and some part of the substantial but largely invisible Soviet contingent – invisible because so many were concealing their identity (with Western connivance) out of fear of forced repatriation. The Soviet DPs, or for that matter the first-wave Russian émigrés who merged with them in the DP camps, are never explicitly discussed in Nasaw’s book, though individual ‘Russians’ make occasional fleeting and unexplained appearances. However, having struggled in the paragraph above to summarise these national complexities, I felt a rush of sympathy with Nasaw – to hell with them, he must have thought, let’s just leave them out.

Jews constituted only a small proportion of displaced persons in 1945, for the simple reason that not many of them survived the Nazi concentration camps. The majority of DPs had been taken to Germany during the war as forced labour or had left their homes in occupied territories with the retreating Germans at the end of the war; some were Soviet prisoners of war who had escaped forcible repatriation in 1945. But the Jewish contingent expanded unexpectedly in 1946 when Polish Jews who had survived the war in the Soviet Union and then been repatriated to Poland found their former homeland inhospitable and moved on to the West. The Americans (though not the British) were willing to accept the new arrivals as DPs, and their arrival briefly pushed the Jewish proportion up to about a fifth of all DPs.

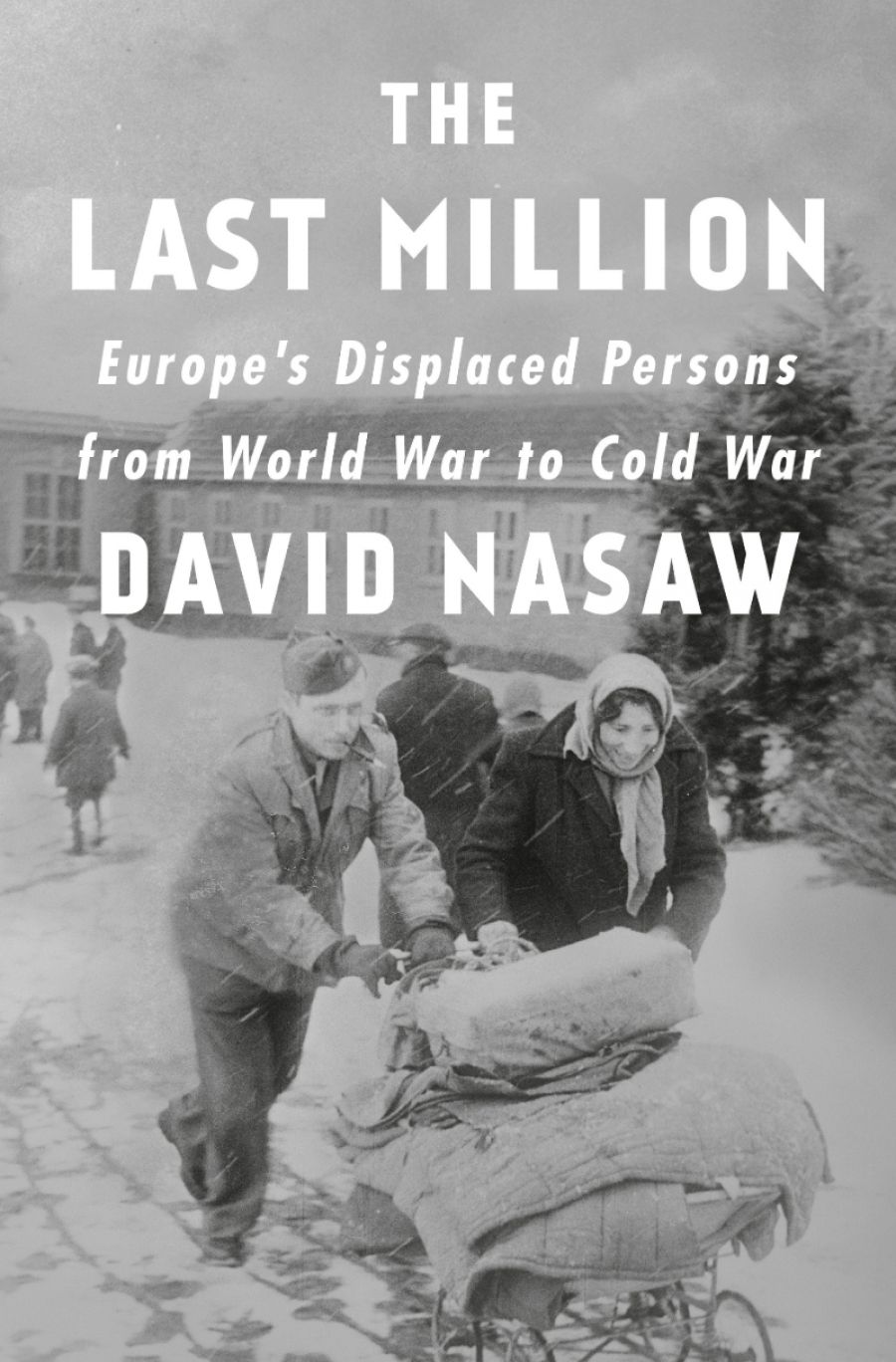

Refugees in Berlin, 1945 (akg-images/Alamy)

Refugees in Berlin, 1945 (akg-images/Alamy)

There were many knotty problems about the DPs to be dealt with, the most difficult concerning the Jewish ones. They could not be repatriated to their countries of origin, both because they refused to go and because those countries did not want them. All the wartime allies (including the Soviet Union) were agreed on their non-repatriability, but a sharp difference of opinion developed between the United States and Britain about what to do with them. The former – in favour, like the Soviet Union, of the creation of a new Jewish state in Palestine – thought they should be allowed to go to Palestine (in the immediate postwar period still under British mandate), while the British resisted. Until the State of Israel was finally created in 1948, the Jewish DPs remained in limbo. Most of them stated their desire to go to Palestine, although once the Jewish state was actually created and civil war with the Arabs ensued, some changed their minds and decided that the United States or some other Western country would be a safer destination.

President Harry Truman started off generously admitting some DPs outside of normal immigration quotas, but when most of them turned out to be Jews, there was a domestic backlash. Those who felt that admitting Jewish DPs was a moral obligation, given their sufferings under the Nazis, pushed for more expanded admission of DPs, but this backfired when the Displaced Persons Act (1948), the subject of much Congressional argument and behind-the-scenes politicking, ended up privileging DPs from the Baltics and disadvantaging Jews. This was corrected in subsequent amendments, but it took several years of complex and intensive lobbying of ethnic and religious groups, with the Catholic Church entering the fray on behalf of Poles. By the time of the second amendment to the Act in 1950, Cold War anti-communism was in full swing, resulting in a strict prohibition of entry of any migrant who had been a communist (a problem for former Soviet citizens, if they were rash enough to drop their disguises as West Ukrainians or Poles) or a Nazi (not a big problem for DPs, even actual collaborators, since most of them had served in the German regime army or civilian administration of occupied territories without joining the Nazi party). But in any case, there were special exemptions for DPs who had worked for US intelligence in Europe (and often for German intelligence earlier), and a new US propaganda initiative featured DPs from communist countries ‘choosing freedom’ over persecution at home.

Australia, with a population of only seven million, took more postwar DPs in absolute terms than any country except the United States, and had some of the same concerns about communists and relative tolerance of collaborators among the migrants as the United States. This remarkable episode is often subsumed into the larger story of mass postwar arrival of ‘New Australians’ of non-British stock, including Italians, Greeks, and Eastern Europeans, and the consequent problems of assimilation. Nasaw gives short shrift to Australia, but let’s hope that his Cold War story reminds us that we have our own Cold War story of DP immigration to tell.

Comments powered by CComment