- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A tussle with the past

- Article Subtitle: Two different readings of the Palace Letters

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In April 2011, the landmark High Court victory of four elderly Kenyans revealed a dark episode in British colonial history. Between 1952 and 1960, barbaric practices, including forced removal and torture, were widely employed against ‘Mau Mau’ rebels, real or imagined. Upon the granting of independence in 1963, thousands of files documenting such atrocities were ‘retained’ by the British authorities, eventually coming to rest in the vast, secret Foreign and Commonwealth Office archives at Hanslope Park. Now a small portion of that archive was opened to scrutiny, and a tiny ray of light shone on one of history’s greatest cover-ups.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

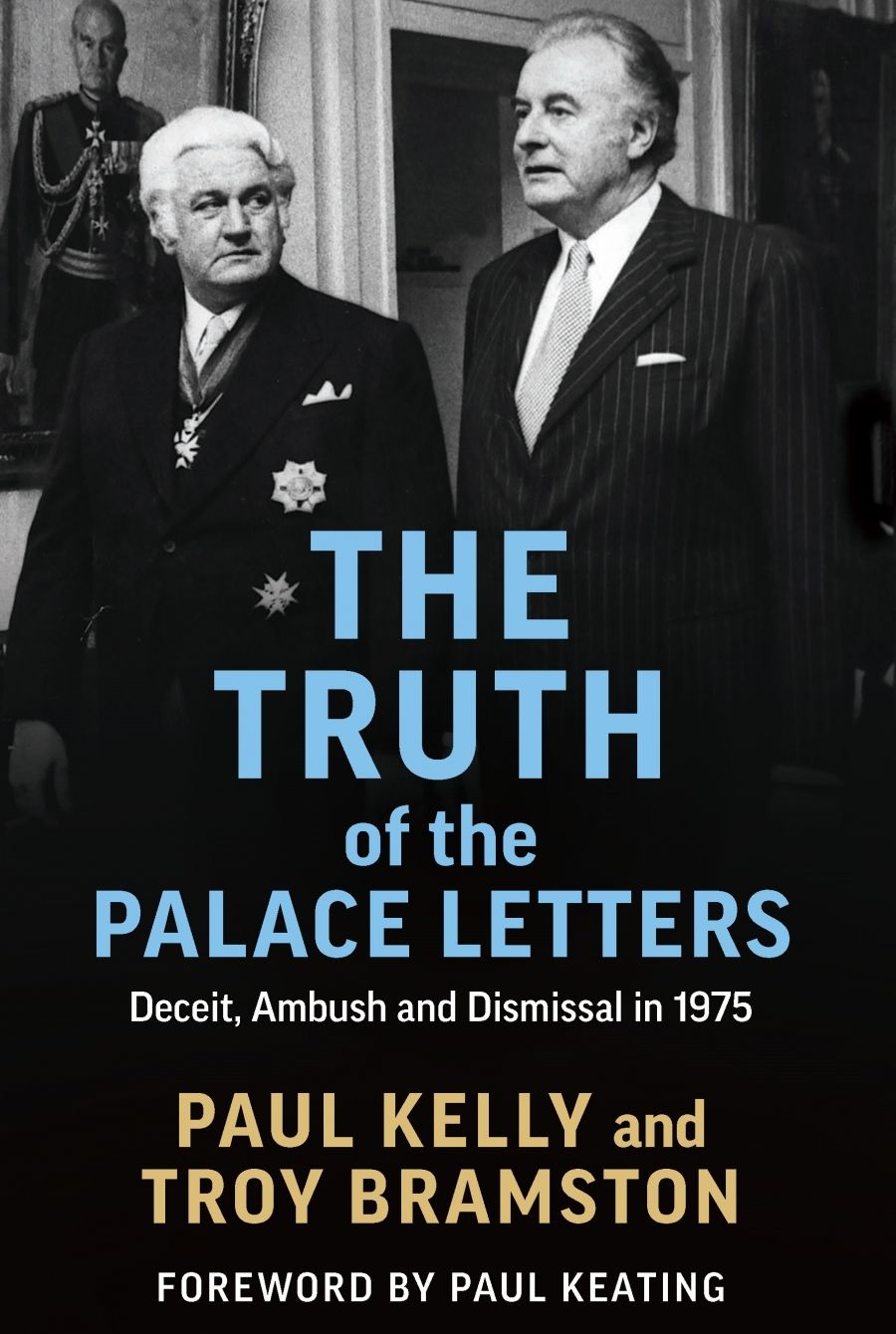

- Book 1 Title: The Truth of the Palace Letters

- Book 1 Subtitle: Deceit, Ambush and Dismissal in 1975

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $29.99 pb, 272 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Xz14b

- Book 2 Title: The Palace Letters

- Book 2 Subtitle: The Queen, the Governor-general, and the Plot to Dismiss Gough Whitlam

- Book 2 Biblio: Scribe, $32.99 pb, 281 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_SocialMedia/2021/Jan_2021/The Palace Letters.jpg

- Book 2 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/q5EjN

The year 1975 saw Australia’s own colonial struggle play out in Canberra, ending on November 11 with the dismissal of progressive nationalist Gough Whitlam by the Queen’s representative, Governor-General Sir John Kerr. To say this was a formative experience for modern Australia is a drastic understatement. Much as with the assassination of John F. Kennedy, or the death of Princess Diana, everyone of a certain vintage can remember precisely when they received word of Whitlam’s dismissal. Unsurprisingly, assessments of the event have fallen along partisan lines neatly encapsulated in the two works here reviewed. Do they show Australia’s monarchical ties to be a ‘remnant of colonialism … untenable for Australia as an independent nation’ (Hocking), or display a benign sovereign ‘hostage to the Governor General’ and other domestic schemers (Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston)?

Hocking had to make a difficult decision in early 2016. Since first sighting evidence of their existence a decade earlier, Hocking had been on the search for what have since become known as the ‘Palace Letters’ – correspondence between Kerr (in his capacity as governor-general) and Queen Elizabeth II, or rather her then private secretary, Martin Charteris. After numerous enquiries, diligent archival excavation, and a little luck, it was revealed that the National Archives of Australia (NAA) indeed held not one but two copies of this correspondence: the official files and a copy made by the governor-general’s official secretary in 1977. Hocking was denied access to both.

John Kerr (KEYSTONE Pictures USA/Alamy)

John Kerr (KEYSTONE Pictures USA/Alamy)

Such archival disappointments are well known to historians. Access restrictions and instruments of deposit can keep portions of the personal papers of influential Australians under lock and key, either for a set period or at the discretion of surviving relatives. We have all found what appears to be the perfect manuscript file, only to learn from an apologetic archivist that it will sit unopened in the stacks for potentially decades to come. Hocking’s case was different on two counts. First, this official correspondence was marked as ‘personal’, an incredible categorisation given that it was the product of a public servant performing his duties. Second, the lengths to which the NAA was willing to go to maintain that status were boundless. Restrictive access conditions are one thing, but their alteration during legal proceedings via methods that can only be described as underhanded is quite another.

Having exhausted her avenues with the NAA itself, Hocking launched an appeal in the Federal Court in September 2016. The Palace Letters is at its most riveting when Hocking’s meticulous archival research dovetails with the cut and thrust of courtroom drama. Her legal team – including Gough’s son, Antony Whitlam QC – rely on notes scrawled upon early drafts of what became the Archives Act (1983) to challenge the NAA’s claims to the exempted status of vice-regal correspondence, just one of many moments in Hocking’s narrative designed to convince historians of their real-world significance. The NAA, particularly its current director-general, David Fricker, is the goliath against which our plaintiff contends, often with the spectre of government or crown looming ominously nearby. Those who have felt the consequences of repeated budgetary cuts – including year-long delays to access records, which almost require a small mortgage to acquire in decent numbers – will no doubt bristle at the largesse of Fricker’s chequebook, at least when it comes to the maintenance of state secrets.

Hocking’s book, chronicling in vivid detail her journey from bemused researcher to High Court victor, offers only a few chapters on what the letters tell us about the dismissal itself. This is a personal narrative from someone who has written much on the topic: including her authoritative two-volume biography of Whitlam (2008, 2012), The Dismissal Dossier (2017), and voluminous public commentary (including the cover feature in the April 2020 issue of ABR). Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston, News Corp columnists with significant press gallery experience, have clearly not yet said their piece. This is despite easily challenging Hocking’s word count: this is Kelly’s fourth book on the topic, and Bramston’s second. The Truth of the Palace Letters is a direct challenge to Hocking’s reading of the correspondence, accusing her of weaving ‘a web of intrigue’ that relies at its core on ‘a misunderstanding of the relationship between the Governor-General and the Palace’.

Kelly and Bramston are on the same side as Hocking – believers in the grand cause of an Australian republic – though reading their contribution does make one sceptical of such a claim. The pair’s disdain for Hocking’s ‘conspiratorial’ world view is palpable, and their willingness to grant the benefit of the doubt is seemingly endless. Charteris’s long correspondence with Kerr, including the former’s ‘extraordinary’ insistence that the Reserve Powers – the right of governors-general to dismiss elected governments – indeed still exist, is to Kelly and Bramston merely an act of ‘indiscretion’. Discussion by the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office of means to avoid the queen’s being dragged into Australian political contest is to Hocking a ‘manifestly improper … intervention in Australian politics’, and a plot to ‘deceive the Prime Minister’, yet Kelly and Bramston see such discussion as ‘entirely legitimate’ and claims to conspiracy ‘untenable’.

At the very least, the three can agree on one villain in this piece: John Kerr himself, though the reasoning differs widely. To Hocking, Kerr is ‘simpering’, a weak man prone to flattery and, at the hands of Charteris, Fraser, and others, manipulation. However, Kerr was himself a master manipulator in Kelly and Bramston’s narration, whose campaign of deception was as underhanded as it was inexplicable. Whether readers will be swayed from their established positions by either volume is doubtful. But the battle lines are clearly drawn.

In the end, it is not Whitlam, Kerr, Fraser, or any other individual at the centre of these volumes, but history itself. ‘[A]s a historian and as an Australian whose history these letters tell,’ Hocking protests, the locking up of the Palace Letters at royal prerogative ‘was a personal affront and a national humiliation’. As well as a matter of national pride, history is also something to which we owe a responsibility, and must answer. Enquiring with Sir Anthony Mason, a High Court judge and Kerr’s confidant during the crisis, as to whether he would speak about the matter ‘in the interest of history’, Mason responded simply, ‘I owe history nothing.’ To Hocking this was ‘a statement of the most remarkable moral cowardice’.

But is history a confessional at which one seeks absolution or perhaps judgement? As Joan Wallach Scott argues in her short book On the Judgment of History (2020), ‘there is no history (or History) apart from what we make of it; no higher court of judgment than our own moral compass; no way to disentangle moral argument from political purpose’. Does the addition of these Palace Letters to the public archive, finally achieved in May 2020 after a drawn-out but, in the end, near unanimous High Court judgment, promise to finally right the wrongs of 1975? One cannot help but think that this places too much faith in history’s power to heal national wounds.

‘History is an endless tussle with the past and what we know about it – and what we don’t yet know about it,’ Hocking helpfully reminds readers. Perhaps more important is the analysis we make of it. The authors of both books mount strident defences of their world views in closing arguments. For Hocking, the lesson in these letters is that of ‘independence, accountability and transparency’, causes that cannot be realised ‘until we complete the post-colonial project of national autonomy’. Far from an invocation to the rhetorical barricades, the events of the dismissal are in fact now ‘passing into history’, claim Kelly and Bramston, and the ‘revisionist story’ that Hocking offers is an ‘insult to its memory’, not to mention a danger to the republican cause itself.

If contemporary debates in Britain on the place of the empire in national memory are anything to go by, the accumulation of evidence for colonialism’s dark past – from mass violence in Kenya to concocted constitutional crises in Australia – only cements entrenched views, driving partisans and apologists to new heights of fantasy and self-soothing. Critics, then, cannot rely on history itself to change well-established patterns of thought, prejudice, and privilege. Only the hard slog of politics can do that.

Comments powered by CComment