- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Rock music does not usually accommodate the likes of Dave Graney. Few Australian performers have been as resilient, and few have presented as many ideas in song form. While his contemporaries – Nick Cave, Tex Perkins, Robert Forster, and the late Grant McLennan – have not strayed far from blueprints forged during the late 1970s, Graney’s music and writing have undergone striking reinvention over thirty years. Equally, few of Graney’s generation have met with such indifference from the Australian public, except for a year or so in the mid-1990s, when, ‘for a brief moment’, in Graney’s words, ‘too many people listened, as opposed to too few … walking in on a line I’d been stringing out for quite a while’.

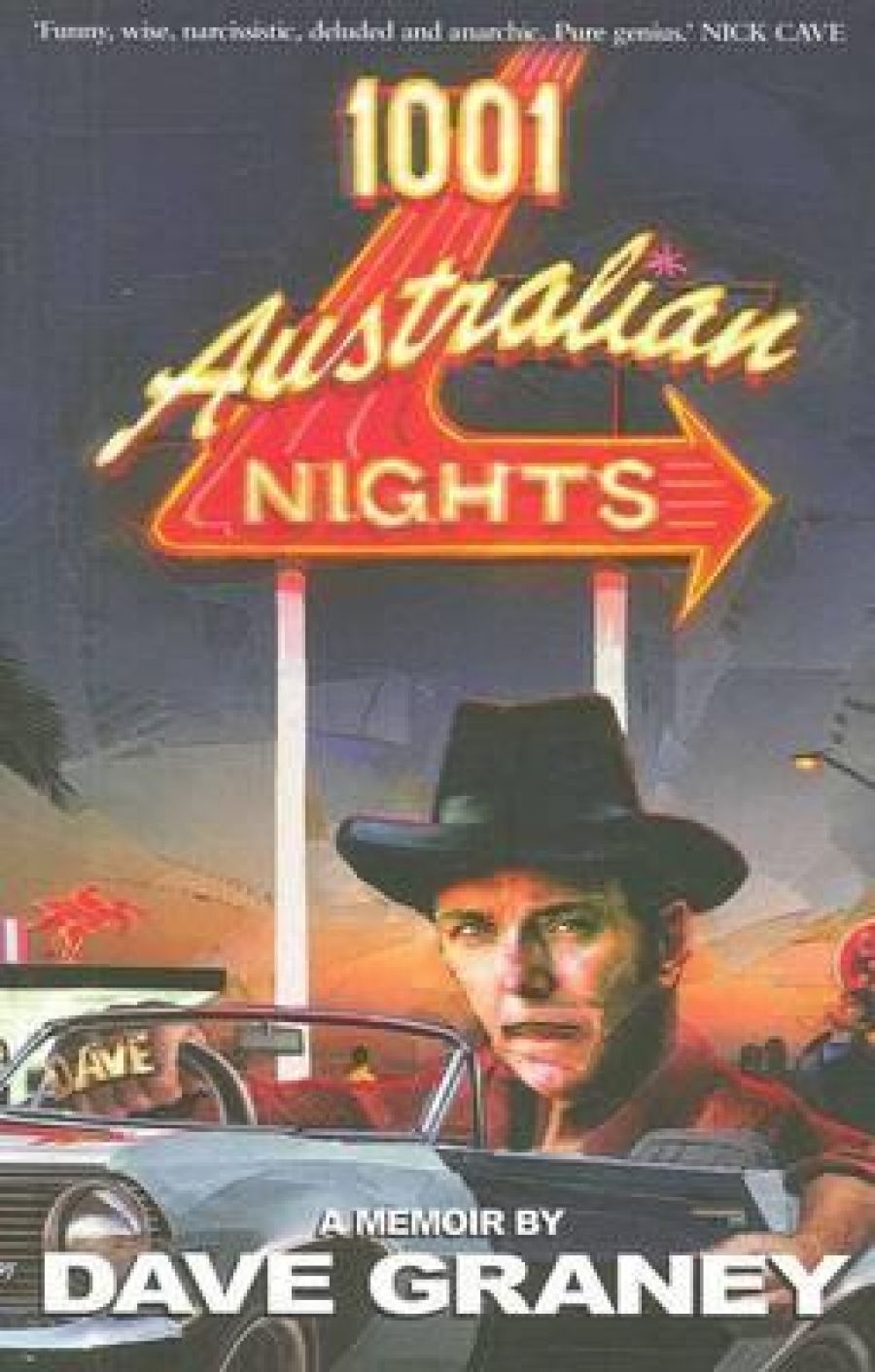

- Book 1 Title: 1001 Australian Nights

- Book 1 Biblio: Affirm Press, $29.95 pb, 256 pp

The main reason for Graney’s commercial sidelining is his refusal to conform to audience perceptions of how a rock performer should behave. His mode is adversarial and highly coded with ‘tongues’, or references to arcane cultural influences. In what becomes a mantra throughout Graney’s memoir, 1001 Australian Nights, emotional pleas in music are strictly ‘for squares’. ‘I find songs about love and wanting really dull … There are some people with great anxieties on display and people love it. I find people like that irritating to be around. You do it once and then you do it twice and it’s an act.’ His alternative has been to cultivate a slew of performance aliases that hold the audience at a stiff arm’s length.

Graney was born in the South Australian timber-mill town of Mount Gambier, birthplace of Robert Helpmann and Max Harris. He remembers it as a ‘Sad, dusty, spooky’ place, ‘groaning with dashed dreams and sick livestock’. Before his exposure to punk music, Graney identified the townspeople’s ‘heroic’ way of being strangely ‘there and not there’, working and drinking to excess against a bare landscape. As well as informing his overall ‘modal sense’, the area’s geography and after-hours culture are directly referenced throughout Graney’s discography, from early solo records such as My Life on the Plains (1989) and I Was the Hunter and I Was the Prey (1990), with their general ‘buckskin country’ aesthetic and mention of Penola and football in the songs ‘Everything Flies Away’ and ‘$1,000,000 in a Red Velvet Suit’, to the songs ‘You Had to Be Drunk’ and ‘I Was a County Boy’ on the recent album We Wuz Curious (2008). The casual brutality of his home town gave Graney his ‘South-Eastern tongue’, a detached air at odds with regular, personality-driven songwriting: ‘I was shady. People laughed. It’s all they know how to do. I like it that way … I didn’t want to put my anguish out front. That would have been undignified. I wanted my anguish to be the hidden core.’

After leaving Mount Gambier, aged eighteen, bound for Melbourne via Young, Sydney, Brisbane, Townsville, Cairns, and many small towns in between, Graney sought out the same kind of unknowable characters in music and literature. Jerry Lee Lewis, Jim Morrison, Alan Vega, and especially Lou Reed were hard entertainers who gave little of themselves, compelling audiences to make sense of their acts themselves. (‘Bravo!’ Graney applauds. ‘Let the cubes crawl through the ashes.’) The inscrutable protagonists of American hard-boiled writers such as James M. Cain, Cornell Woolrich, and George Sims (aka Paul Cain), as well as their Hollywood counterparts in films The Thin Man and Point Blank, were even more potent, pre-rock influences ‘providing a tone and a voice’ to appropriate. Fronting The Moodists, his first serious band and arguably Australia’s most important post-punk group, Graney penned the noir-inspired tunes ‘Double Life’, ‘Chad’s Car’, and ‘Gone Dead’.

On Cain’s Double Indemnity (1943), Graney comments, ‘I loved the writing for the hard-boiled unequivocal tone of the narrator.’ 1001 Australian Nights, written in similarly emphatic language, is full of dialogue, short sentences, pithy observations, and crude humour. Surrealist literature is another declared interest, and Graney’s exclamatory tone recalls the sensational swagger of Comte de Lautremont’s Les Chants de Maldoror (1868). Little is made of Graney’s earthbound life – meeting his wife and long-term music collaborator, Clare Moore, is dealt with in a single paragraph – and little, too, of the technicalities of songwriting. Mostly, the book is a compendium of thoughts on show business, tour diaries, and a history of the making of Graney’s ‘own cosmology’.

The reproduction of song lyrics throughout the text demonstrates Graney’s peppering of ‘content’ in his music, and an appendix with annotated discography identifies the ‘tongues’ at play on each of his albums. Unlike those ‘mug lairs … trying just a bit too hard to jump out of their skin’, Graney’s tactic is to bring a highly developed context to his audience – his ‘velvet fog’, his ‘lurid yellow mist’ – in opposition to the sentimentality of rock’s ‘wasteland of howling dopes’. There is no overt ironic distance in what he does, but to some outsiders Graney can seem insincere, even ‘schlocky’. After Graney performed at a Toowomba pub in ‘leather pants, a leather waistcoat and a short leather jacket and a black leather cap’, an audience member compared him to ‘Cher, or was it Freddie Mercury?’ Graney’s retort: ‘She was ignorant of how crude her critique was.’ 1001 Australian Nights will similarly divide readers into those who are willing to ‘see’ Graney and those ‘squares’ who are not.

Comments powered by CComment