- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: United States

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Blue shirts and bullwhips

- Article Subtitle: Canonising John R. Lewis

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

John R. Lewis, who died in July 2020, was an extraordinary man. Born poor, the son of tenant farmers in rural, segregated Alabama, Lewis was one of America’s most prominent civil rights leaders by the age of twenty-three. He spoke at the March on Washington in 1963, when Dr Martin Luther King Jr delivered his famous ‘I have a dream’ speech.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

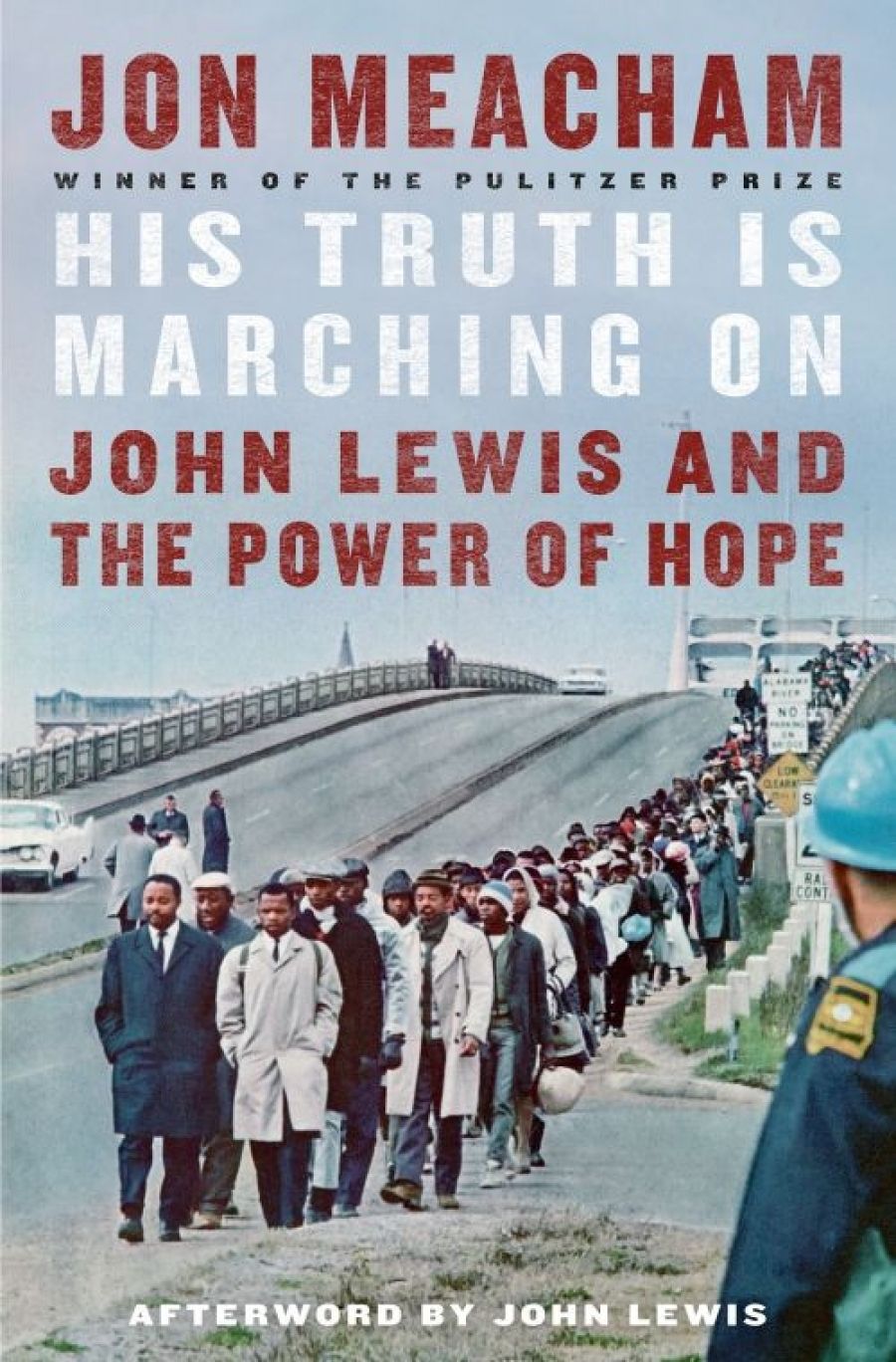

- Book 1 Title: His Truth Is Marching On

- Book 1 Subtitle: John Lewis and the power of hope

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $52.99 hb, 354 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/52Mvj

Growing up in Pike County, Alabama, Lewis was precocious and stubborn. He hated the back-breaking, poorly compensated work of picking cotton and bridled at his family’s lot. At sixteen, he heard the clarion voice of Dr King on the radio. ‘When I heard King, it was as though a light turned on in my heart. When I heard his voice, I felt he was talking directly to me. From that moment on, I decided I wanted to be just like him.’

While he studied at the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Lewis’s commitment to Dr King and the civil rights movement grew. A fellow student told him: ‘John, you gotta stop preaching the gospel according to Martin Luther King and start preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ.’ For Lewis, the two were becoming one and the same.

To desegregate lunch counters in downtown Nashville, Lewis and other members of the Nashville Student Movement organised sit-ins, occupying lunch counter seats reserved for whites and refusing to leave. As the group held more sit-ins, the response from store owners and gangs of local thugs became increasingly violent. Some protesters were arrested. Lewis was beaten and nearly killed. Nonetheless, the students remained steadfastly non-violent. It was an article of their faith.

In 1961, Lewis joined the first Freedom Ride. Black and white students rode together on interstate buses and used ‘White Only’ facilities in open defiance of Southern segregation policies. The Freedom Riders were met with violence. Some riders were beaten. Others arrested. In Alabama, members of the Ku Klux Klan threw a Molotov cocktail into the bus, and attacked escaping passengers. Local police stood by or joined in the attacks on the riders.

As the violence escalated, the Kennedy administration and older civil rights leaders tried to stop the Freedom Rides. The students were set on continuing. As Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) strategist Diane Nash explained:

If the Freedom Rides were stopped because of violence, and only because of violence, then the nonviolent movement was over … Give the racists this victory and it sends the clear signal that at the first sign of resistance, all they have to do is organize massive violence, the movement will collapse, and the government won’t do a thing. We can’t let that happen.

In 1963, Lewis was elected chairman of the SNCC. As part of the ‘Big Six’ – leaders of civil rights organisations – he met with President Kennedy. However, the elevation did not diminish Lewis’s willingness to take his place on the front lines. Famously, on 7 March 1965, Lewis led a march from Selma to Montgomery for voting rights. The marchers began to cross Edmund Pettus Bridge. From the opposite side of the bridge, Alabama state troopers and a local posse advanced toward the marchers, sweeping forward, in Lewis’s words, ‘like a human wave, a blur of blue shirts and billy clubs and bullwhips’. Lewis fell, struck in the head with a billy club. As he tried to rise, he was struck again and lost consciousness. As tear gas dispersed the marchers, the troopers continued the assault. One of the men, on horseback, lashed a running woman with his bullwhip. ‘O.K., nigger. You wanted to march, now march!’ The images provoked national outcry and contributed to the passage of the Voting Rights Act 1965.

Congressman John Lewis together with the Reverend Jesse Jackson and Hosea Williams crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama (Linda Schaefer/Alamy)

Congressman John Lewis together with the Reverend Jesse Jackson and Hosea Williams crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama (Linda Schaefer/Alamy)

Although at times simplistic and selective, His Truth Is Marching On offers a vivid account of pivotal events in the civil rights movement. Meacham deftly explores tensions between the leaders of the movement and their sometimes hesitant allies in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

Tensions also existed within the movement itself. Although it achieved concrete legislative gains, more radical forces emerged, challenging the religious and non-violent pillars of the existing leadership as well as the perceived deference of the movement’s leaders to presidents Kennedy and Johnson. In 1966, these forces removed Lewis as chairman of SNCC and installed Stokely Carmichael, who observed: ‘I don’t go along with this garbage that you can’t hate, you gotta love. I don’t go along with that at all. Man, you can, you do hate.’

Although dispirited, Lewis moved into the political sphere, joining Robert Kennedy’s campaign for president in 1968. With the assassinations of King in April and Kennedy in June, and with the eventual election of Richard Nixon as president, the year brought an unofficial end to the civil rights movement. Here, His Truth Is Marching On ends abruptly (save for an epilogue, briefly describing Lewis’s first Congressional race). In doing so, Meacham preserves an untouched image of Lewis as a hero and icon of the civil rights movement, but leaves an unfinished story.

Lewis went on to serve for thirty-four years as a Congressman. Though a reliable Democratic vote, and a resonant moral voice, Lewis struggled to translate the major victories of the civil rights movement into economic and broader progress for African Americans.

The author’s unqualified admiration for his subject is present throughout the book. In Meacham’s account: ‘John Robert Lewis embodied the traits of a saint in the classical Christian sense of the term.’ However, by avoiding more complicated or difficult questions and only occasionally noting criticisms of Lewis, the picture of the man that emerges is necessarily shallow. Hagiography is rarely penetrating.

Despite these limitations, and despite a heavy reliance on Lewis’s evocative book Walking with the Wind: A memoir of the movement (1998) and on interviews with Lewis, His Truth Is Marching On captures key moments in the civil rights movement and showcases Lewis’s courage and moral stature. It also elevates some of the movement’s lesser-known heroes. It is well worth reading.

Comments powered by CComment