- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Grace and burdens

- Article Subtitle: Robert Adamson’s elegant new Selected Poems

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Robert Adamson is the fact that he is still alive. One of the ‘Generation of ’68’ and an instrumental figure in the New Australian Poetry (as announced by John Tranter’s 1979 anthology), Adamson has continued to write and adapt while also bearing witness to the premature deaths of many of that visionary company. As Adamson’s friend and fellow poet Michael Dransfield (1948–73) once put it, ‘to be a poet in Australia / is the ultimate commitment’ and ‘the ultimate commitment / is survival’. The poems in this volume attest to the grace and burden of being one of Australian poetry’s great survivors – of the countercultural mythology of the ‘drug-poet’, alcoholism, and the brutalities of the prison system (recounted firsthand in his 2004 memoir, Inside Out). ‘The show’s to escape / death’, Adamson observes of the Jesus bird (sometimes called a lilytrotter), a lithe performer and canny survivalist that affords this most ornithologically minded of authors a telling self-image.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Reaching Light

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Flood Editions, US$19.95 pb, 227 pp

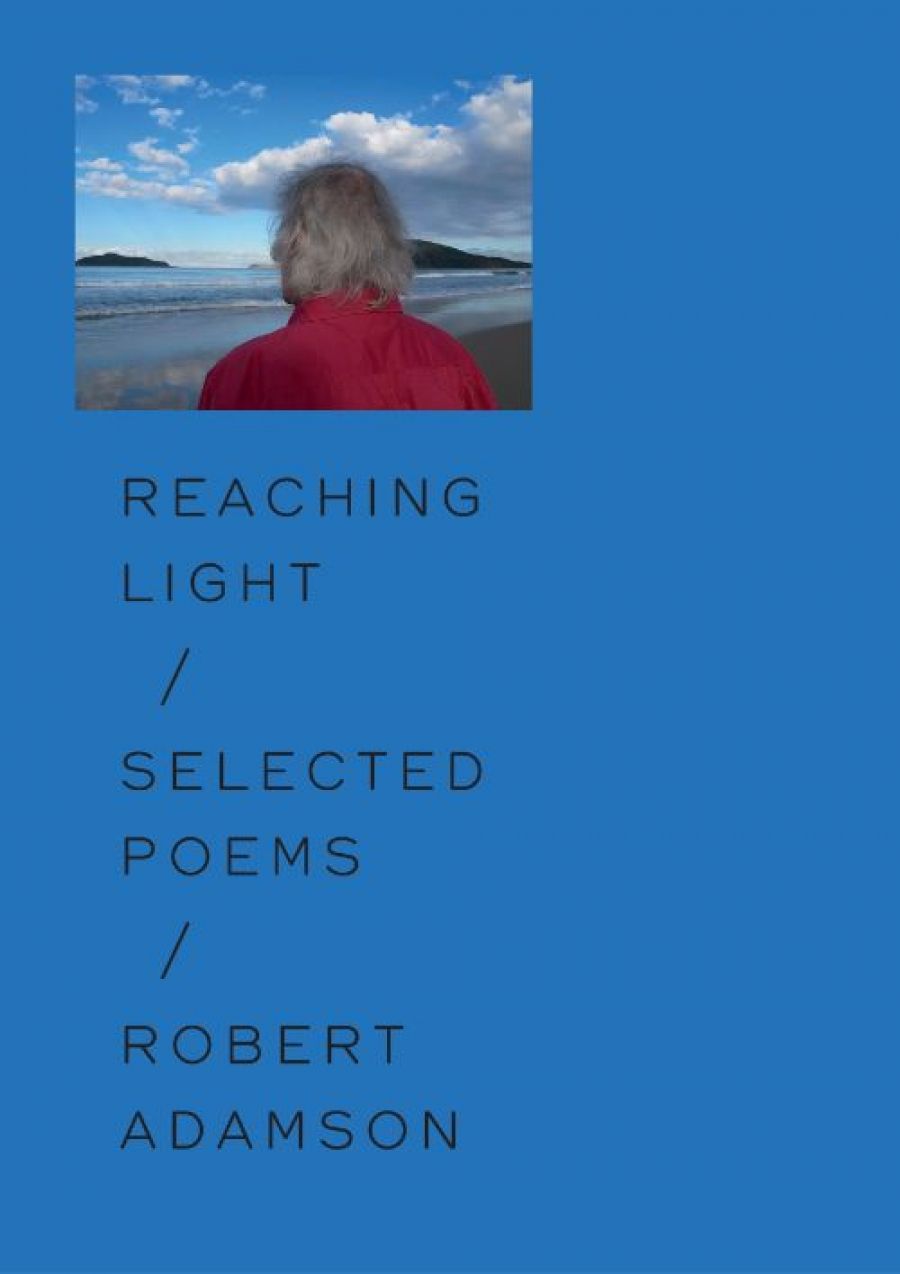

As befits a poet and editor who has fostered collaboration between the visual and verbal arts, Reaching Light is an elegant production with its matte cobalt-blue cover setting off a pair of author photographs taken by Juno Gemes (Adamson’s wife). Spanning four decades of Adamson’s ‘ultimate commitment’, the selection by Devin Johnston (who also provides a scrupulous introduction) is divided into a chronological sequence of three sections. The first of these covers the period from Adamson’s début collection, Canticles on the Skin (1970), to The Law at Heart’s Desire (1982). In it, we see two competing tendencies in a sensibility that is, on the one hand, eminently sensual and attuned to the vicissitudes of the flesh, and, on the other, inclined towards the purity of abstraction and an ascetic pursuit of form. The more successful poems are ones in which the former gains the upper hand, as in ‘Toward Abstraction / Possibly a Gull’s Wing’, which opens with a vision of sand’s ‘absolute flatness’ before narrowing its focus to a close-up of a dead tern: ‘Its wings unfold like a fan, sea lice fall from the sepia / feathers and the feathers take flight.’ This image is straight out of the decadents’ manual, but where Baudelaire would have lingered on the parasitic vitality of the lice (see ‘Une Charogne’), Adamson is determined to rescue a moment of delicacy out of this scene of putrescence.

Robert Adamson (photograph by Juno Gemes)

Robert Adamson (photograph by Juno Gemes)

That the young Adamson was an ardent Symbolist is apparent in a number of the early poems even as they record a growing disenchantment. ‘Surely,’ Adamson writes in the first of the ‘Sonnets to be Written from Prison’, ‘there must be some way out of poetry other than / Mallarmé’s: still life with bars and shitcan.’ As Tranter once observed, the antinomian elements of Adamson’s life should have led him towards the swashbuckling Rimbaud rather than the schoolmasterly Mallarmé. It is the former who features in the hard-to-forget ‘Rimbaud Having a Bath’, a poem that evinces great poise in recounting a rape: ‘To have been held down in a park / the animal breath in your face’ (note the tone of composure in the infinitive construction; a more opportunistic poet would have begun at ‘Held down’). Poetry is part of the process of repairing ‘the carnage under the skull’ resulting from this ordeal, but in taking a bath afterwards the poet has ‘betrayed his art having washed / the vermin from the body and the heart’. Adamson seems drawn to violent encounters that offer proofs of vocation; this is partially why fishing – with its routine acts of peeling, hooking, and cutting catalogued in so many of the poems – is crucial to his self-mythologising. There is, I think, an affinity between the decadent poet making every experience count and the fisherman plying his trade: for both, the violation of the flesh is as much a sacrament as a desecration.

Readers familiar with the contours of Adamson’s life may well be tempted to guess at the personal experiences that feed into a poem like ‘Rimbaud Having a Bath’. It’s a constant temptation given the proximity of biographical person to poetic persona in many of the later pieces, with their patterns of allusion, dedication, and recollection. While Adamson has often been acknowledged as a scion of the Pound–Olson school, his poems continue to evince the influence of poets grouped (not always helpfully or accurately) under the ‘confessional’ label. When Adamson’s disgust at the political climate is set against the Stygian backdrop of the Hawkesbury River, the imagery becomes febrile, morbid, and slightly cartoonish in a manner that recalls Sylvia Plath: ‘They are death men rattling loaded dice, / war-headed malformations of the mind / as an eyeless reaper’. In some of the bird poems, Adamson exhibits that ‘self-forgetful, perfectly useless concentration’ that Elizabeth Bishop extolled as the basis for the creation and enjoyment of art, the almost mystical reverence for ‘a squall of refracted / light in eyes that a human / cannot read – opaque, steadfast’ in ‘Looking into a Bowerbird’s Eye’ reminding us of both poets’ affinity with Gerard Manley Hopkins. Adamson is clearly discomforted by his enthusiasm for confessional poetry, wrestling with this tendency in ‘Clear Water Reckoning’. ‘I steer / away from anything confessional’, the poet declares, before comparing Robert Lowell’s ‘intelligent blues’ to a ‘Jelly Roll of a self-caught mess / deep in spiritual distress’. There is warmth of recognition in this homely image (Adamson was once a baker), but also something jumpy about the sudden tunefulness, as if the rhymed tetrameter lines betoken a commitment to the discipline of craft as a bulwark against formless self-regard.

Adamson’s temperament has mellowed over the years: ‘In the old days I used to think art / That was purely imagined could fly higher / Than anything real’, whereas now such flights of fancy come with ‘a feeling of strange panic’. Recent poems such as ‘Summer’ and ‘Garden Poem’ show Adamson to be a poet of ‘extraordinary actuality’ (in Wallace Stevens’s words), with a prodigious feeling for the domestic accommodation of seasonal and diurnal changes. Much of this shift in sensibility can be attributed to Gemes’s presence in Adamson’s life: ‘You taught me how to weigh the harvest of light.’ This is both a tribute to Gemes’s work as a photographer (literally, a light-writer) and part of a Manichean drama in which the poet figures himself as his wife’s inky counterpart, one unable to resist ‘the lure of dark song’. Adamson’s investment in these light–dark archetypes helps explain the enduring appeal of the Orpheus–Eurydice myth, a story about a failed attempt at reaching light tacitly revised into a tale of survival: ‘I preferred the cover of night, yet here, I stepped / into the day by following your gaze.’

That these lines are placed at the end of the volume suggests a redemptive finality belied by the poet’s restless (and at-times excoriating) self-scrutiny. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Adamson, then, is the fact that he is still alive – and so free of complacency. With Emily Dickinson, he can justly claim: ‘my worthiness is all my doubt’.

Comments powered by CComment