- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The invention of Stoppard

- Article Subtitle: An artist shaped by Englishness

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A tantalising ‘what if?’ emerges from the opening chapters of Hermione Lee’s immense, intricately researched life of Tom Stoppard. On the day in 1939 when the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia, the future playwright’s assimilated Jewish parents were obliged to flee the Moravian town where they lived. They made it to Singapore, only to endure Japanese invasion soon afterward. Stoppard’s mother, Martha, had to move again, and swiftly, with her two sons while her beloved husband, Eugen, a doctor, remained behind to aid with civilian defence. His evacuation ship was destroyed, and he was lost, presumably drowned, a little later. But when Stoppard’s mother boarded her own ship, earlier in 1941, she thought it was headed for Australia. Only later did she learn that India was their destination.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Tom Stoppard

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life

- Book 1 Biblio: Knopf, $59.95 hb, 896 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/PJrAe

The notion is not so preposterous. Lee’s monumental biography, impeccable in its enquiries, built from archive-diving and numerous interviews with intimates of Stoppard’s, as well as generous time spent with the subject, coheres around the idea of Stoppard as an artist shaped by Englishness – and shaped, in much the same way earlier generations of European Jewish intellectuals and creative figures were, by gratitude. Take George Steiner, for example, or Isaiah Berlin. Each man used his dual citizenship of the world to build bridges between the dourly empirical and common-sense-loving English, and the more charismatic intellectual and artistic enterprises of Continental thought and art. Both did so, however, by smuggling their contraband in via diplomatic pouches. Steiner and Berlin were performative English gentlemen, right down to their Jermyn Street spats. It was their ability to look and act the part – the pure sincerity of their belief that, by landing in Britain and making a home there, they had lucked out in geographic terms during a torrid and brutal period across the Channel – that granted them permission to share European passions with the Anglo natives.

For the young Tomas – now Tom Stoppard – plugging away at a pair of minor boarding schools during the 1950s, the stepson of a Larkinesque parody of Englishness and of a mother anxious to bury a past that had buried much of her family at Theresienstadt or Auschwitz, gratitude was the water in which he swam. Lee describes a charming, happy, emollient boy and youth: one who strove to play cricket, lose his accent, and fly fish in a manner that would make Major Stoppard proud. The greatest regret of the playwright’s later life was that he did not make the traditional move to Oxbridge but instead set out at seventeen to become a journalist.

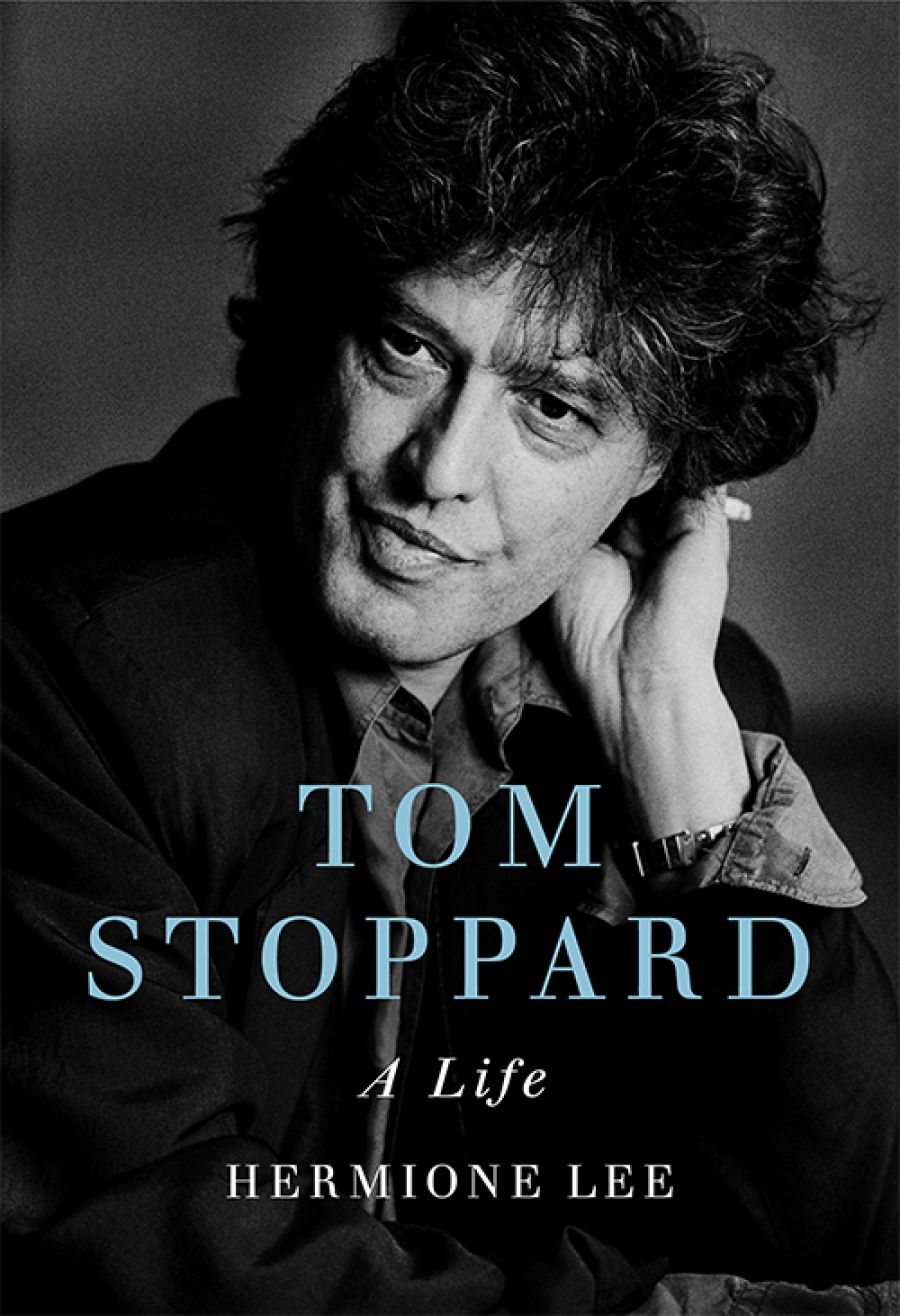

Tom Stoppard at the Venice International Film Festival in 1990 (Gorup de Besanez/Wikimedia Commons)

Tom Stoppard at the Venice International Film Festival in 1990 (Gorup de Besanez/Wikimedia Commons)

Those years in Bristol spent grinding out copy for the Western Daily Press were formative. Postwar Bristol was a regional mecca for theatre. Stoppard became a theatre critic and established an early friendship with Peter O’Toole. He learned to work collaboratively and under pressure of deadline, and he discovered in himself an impatience for literary fame, one that could not be satisfied by the solitary labours of poetry or fiction.

Lee is very good on early Stoppard. Readers gain a pungent sense of the desperation that drove the young man, perennially in debt and unhappily married, to take two minor characters from Shakespeare’s Hamlet and grant them the swelling attentions of his pre-postmodern perspective.

It is also good to be reminded that, from the point of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead’s arrival at the Edinburgh Fringe in 1966, Stoppard was the coming man of English theatre. Harold Pinter may have inherited the Beckettian menace, Arnold Wesker the political engagement, Christopher Hampton the Europhile polish, but it was Stoppard whose talent was to shapeshift in ways that allowed him to borrow aspects of each of these at times while remaining inimitable.

Given the rich social ferment of the 1960s and 1970s in the United Kingdom, the charged geopolitics of the late Cold War, and the shifting baseline of Stoppard’s sense of his Czech roots (his mother, now known as Bobby, withheld for years the true extent of Stoppard’s Jewish background and the losses suffered by his family during World War II), Lee regards her primary responsibility as that of measuring each new play against the evolution in self-conception and political awareness of the playwright. This allows the biographer to insulate Stoppard, to some degree, from accusations that he was an instinctual conservative: a clubbable man who shared a close friendship with reactionary journalist and historian Paul Johnson, allowed his plays to be performed in apartheid-era South Africa, and broke bread with Thatcher and Reagan.

Lee’s argument, over and again, returns to gratitude. Freedom of speech mattered to Stoppard in proportion to his sense of its lack behind the Iron Curtain. It was his growing sense of affinity with the Charter 77 movement led by Czech playwright Václav Havel, who was later to become Czechoslovakia’s last president, that led Stoppard to register and celebrate an enduring sense that, in Cecil Rhodes’s words, often quoted by his stepfather, ‘to be born an Englishman was to have drawn first prize in the lottery of life’.

But it is the plays that properly remain at the centre of Tom Stoppard. Lee is laborious in recreating the specific context in which each performance unfolds. Actors, directors, agents, and financial backers; radio producers, literary publishers, and film company moguls: each constellation of talent and money is fixed in time and space, so that readers might understand the complex interplay of creative endeavour and theatrical realpolitik from which Stoppard’s reputation has been built.

It is tribute to Stoppard’s talent that his plays were so well received, both by peers as hard to impress as Harold Pinter and audiences large and various as those in New York, Sydney, and Prague. But it is an achievement of another order, Lee suggests, that the charming and easy-going playwright could impose his will upon directors and actors without ever gaining a dictatorial reputation.

Here lies the paradox of Lee’s undertaking. The biographer is a friend of the subject and a frequent guest in his home. The Tom Stoppard that issues from her efforts is a warm, intelligent, satisfyingly definitive account. It is not a hagiography by any means, but it is very much an in-house production. A thousand pages in, readers will have been both delighted and drowned in detail. Their sense of Stoppard’s deeper motivations and inner life, however, will remain frustratingly opaque. Critic and theatre director Kenneth Tynan, in a critical New Yorker profile from 1977, makes the point sharply. The cool, glamorous, witty, and dandyish playwright, who balanced so finely an emigré’s exoticism with a typically English sense of balance and order, was not as approachable as he seemed. ‘Tom’s modesty is a form of egoism,’ Tynan concluded. After wading through Lee’s biography, so vast and yet ultimately unrevealing, I suspected much the same.

Comments powered by CComment