- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Diaries

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The calling to write

- Article Subtitle: The latest volume of Helen Garner's diaries

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Unerring muse that makes the casual perfect’: Robert Lowell’s compliment to his friend Elizabeth Bishop comes to mind as I read Helen Garner. She is another artist who reveres the casual for its power to disrupt and illuminate. Nothing is ever really casual for her, but rather becomes part of a perfection that she resists at the same time. The ordinary in these diaries – the daily, the diurnal, the stumbled-upon, the breathing in and out – is turned into something else through the writer’s extraordinary craft.

- Book 1 Title: One Day I’ll Remember This

- Book 1 Subtitle: Diaries 1987–1995

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 hb, 297 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/60J6Q

These diaries cover a clutch of years from the author’s mid-life. H, as I’ll call her, is going through a divorce, her grown-up daughter moves out, and she starts a new relationship, with a married man, a fellow writer. It involves moving back and forth from her home in Melbourne to Sydney where she lives and works in borrowed rooms as she struggles with her new novel. She’s finding fiction hard. Passing through Indianapolis, she writes: ‘I pulled out of my head a single white hair.’ Later, in relation to the man she calls V, she says, ‘I am forty-six-and-a-half and I am humiliated.’ It’s not an easy time.

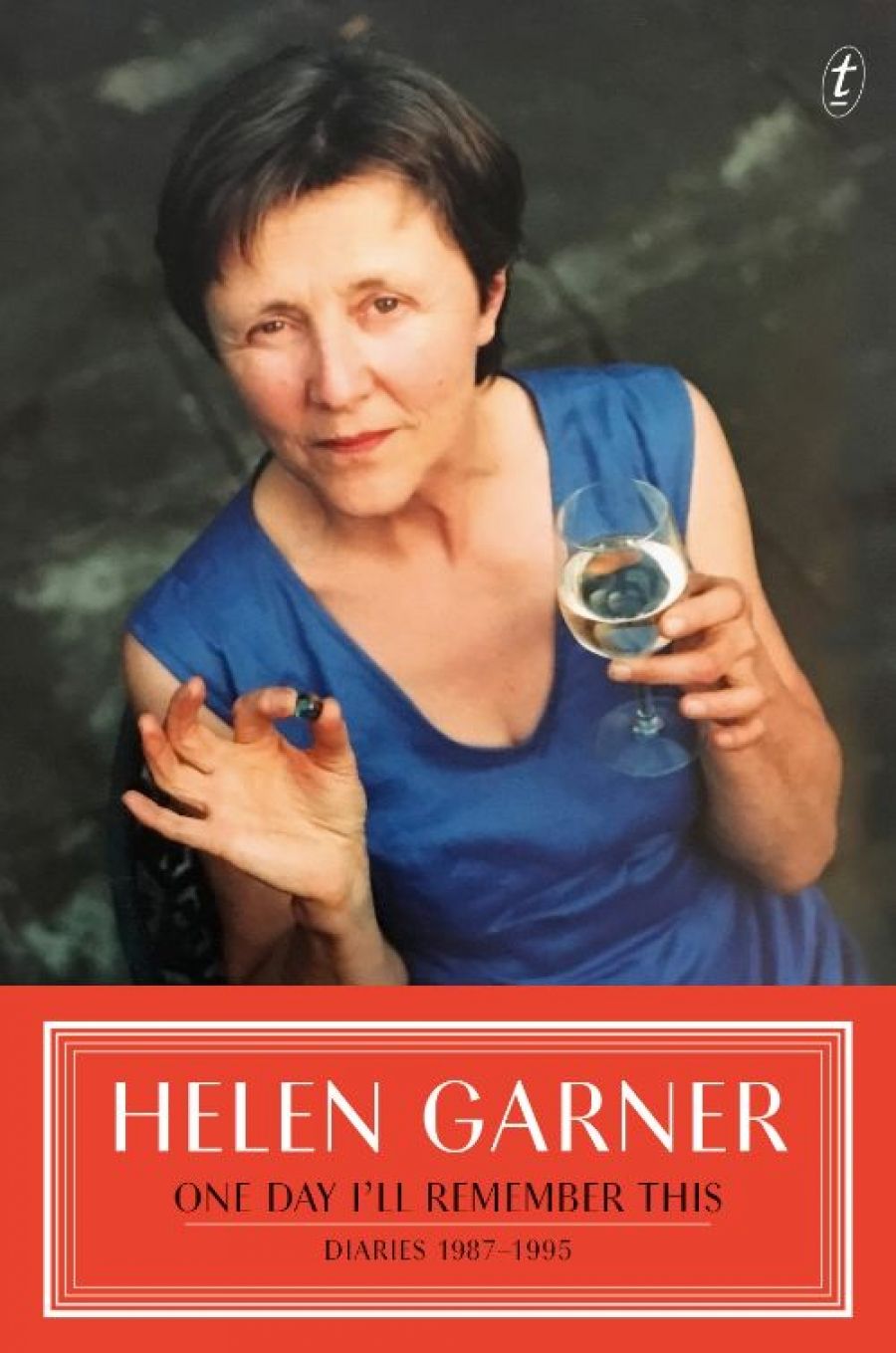

A portrait photograph of Helen Garner (Darren James/Text Publishing)

A portrait photograph of Helen Garner (Darren James/Text Publishing)

The familiar binaries are here: youth and age, visibility and invisibility, Melbourne versus Sydney, men and women; all evoked in prose that needles and dances. ‘Funny how when I come to Sydney my mind works in a different way. I have better, freer ideas. Must remind myself that this is because I don’t live here, rather than a reason for me to move here.’ But further on: ‘Steel-grey Melbourne skies, a cloud at 5pm the colour of gabardine behind the bare elm branches in North Fitzroy. Ground dark and damp. Can’t think how I could have left this city.’

There’s a narrative arc as H commits herself to V and tries to work out a way of cohabiting with him. They are two writers who need their own space and room for their diverging attitudes and ideas. The diaries experience their difficulties as archetypal male–female opposition, inseparable from their love for each other, in a painful, hopeless comedy. It builds to a feminist argument about work and culture. ‘All I need to attend to is that I keep enough of myself free for my work and the hours of private mental time this requires,’ H confides to the page. ‘I mean that my attention to him and his needs should not outweigh my attention to myself for work. All I need! This terribly hard thing, for a woman.’

Around this the book develops other rhythms and finds space for other things – the weather, visits to a place in the country where there always seems to be a koala, travels, books, and all the random noticing that a writer collects. It’s a fluid, selective assemblage. A dream diary weaves through it, with an interior landscape of darker, weirder intimations. At the start, for example, H has a fantasy of V: ‘He is already in my past, a stranger, a finished phase.’ Her friend opines: ‘People think the world is full of couples ... In fact it is made up of triangles.’ The story is over before it has begun. This foreboding is a novelistic strategy, announcing a theme that gains weight as the book goes on. There is a shaping hand at work here: the writer as the ringmaster she says she doesn’t want to be.

Characters are given initials that don’t match who we think they might be in real life, if we know Helen Garner’s biography. That may be to protect the innocent and the guilty. It allows us to read and enjoy this narrative as a kind of fiction. Insiders will have fun puzzling over who’s who, but that’s not the point. There’s a larger point concerning the meaning of art, who speaks for the culture, and how to live as a writer – a woman writing in Australia – that comes to the fore, as so often in Garner’s work. When she gets the proofs of Cosmo Cosmolino (1992), her new fiction, H notices ‘its anxious perfectness. I made up my mind, next time, to blast that aspect of my writing to kingdom come.’ She would do so in non-fiction. She hears about the Master of Ormond College and is soon working on The First Stone (1995): ‘I feel grit start to harden inside me.’

Work bridges life and art in ways that Garner catches in her miniature masterpiece ‘The Life of Art’, published in Postcards from Surfers (1985) as these diaries begin. Work is vocation. She must work to find the writer she can most truly be: ‘one writes only as one can’. It’s a question of self-knowledge. Part of her transition in these years is from fiction to non-fiction, as she invents a new form of autofiction, way ahead of the pack. ‘J’s won his second Miles Franklin,’ she wryly observes. ‘That’s a prize I know I’ll never win.’ She has other brave work to do, creating her own voice and a world that we now call Garnerian.

It all comes to a head in 1989, that epochal year. In the wider world, the fatwa is put on Salman Rushdie for The Satanic Verses. In June, the violence of the Tiananmen Square massacre is shocking news. In November, ‘people are sitting on top of the Berlin Wall ... chipping chunks out of it ... for souvenirs’. McPhee Gribble, Garner’s wonderful publisher, is taken over by Penguin. And on the domestic front, H and V argue. ‘We’re both battling, and our battles clash, as well as our two natures.’ It is as if the third in their relationship is the calling to write.

The book has some tough reflections on what writing is and does and needs. I discovered the author’s deep feeling for poetry and music. H may be reading Proust as a long-haul project in these years, but she has Paradise Lost ‘in the outside toilet’. When she hears a Brahms string quartet on the radio, ‘I knew what the word “grace” meant ... My anger and sadness flowed out of me and were gone.’ No wonder her sentences have such cadence.

I also appreciate what is revealed here about the presence of religion in H’s life. She calls it the ‘Mighty Force’, experienced as a ‘dark column of meaning’. Death is everywhere for her. V says she is obsessed with ‘death, rape, murder and so on’. Against that there is ‘a chance at the soul’. She transcribes a quote from Emerson’s ‘Self-Reliance’ that hints at a meeting place between her writing and what she glimpses spiritually: ‘Prayer ... is the soliloquy of a beholding and jubilant soul.’ Like these diaries.

Comments powered by CComment