- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Reviewing Oliver Stone’s film Salvador for The New Yorker in 1986, Pauline Kael detected a ‘right-wing macho fantasy joined to a left-wing polemic’. That same compound, a politically unstable one, bubbles under the surface of Stone’s autobiography, Chasing the Light. Generally speaking, it is hard to separate judgement about an autobiography from that about its subject, since reading an autobiography is like a long stay at someone’s home, listening to them detail their life story around the dinner table, night after night. The problem is twofold when its author is so politically conflicted. As distinct from a film review, to review Oliver Stone’s autobiography is undeniably to review ‘Oliver Stone’.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

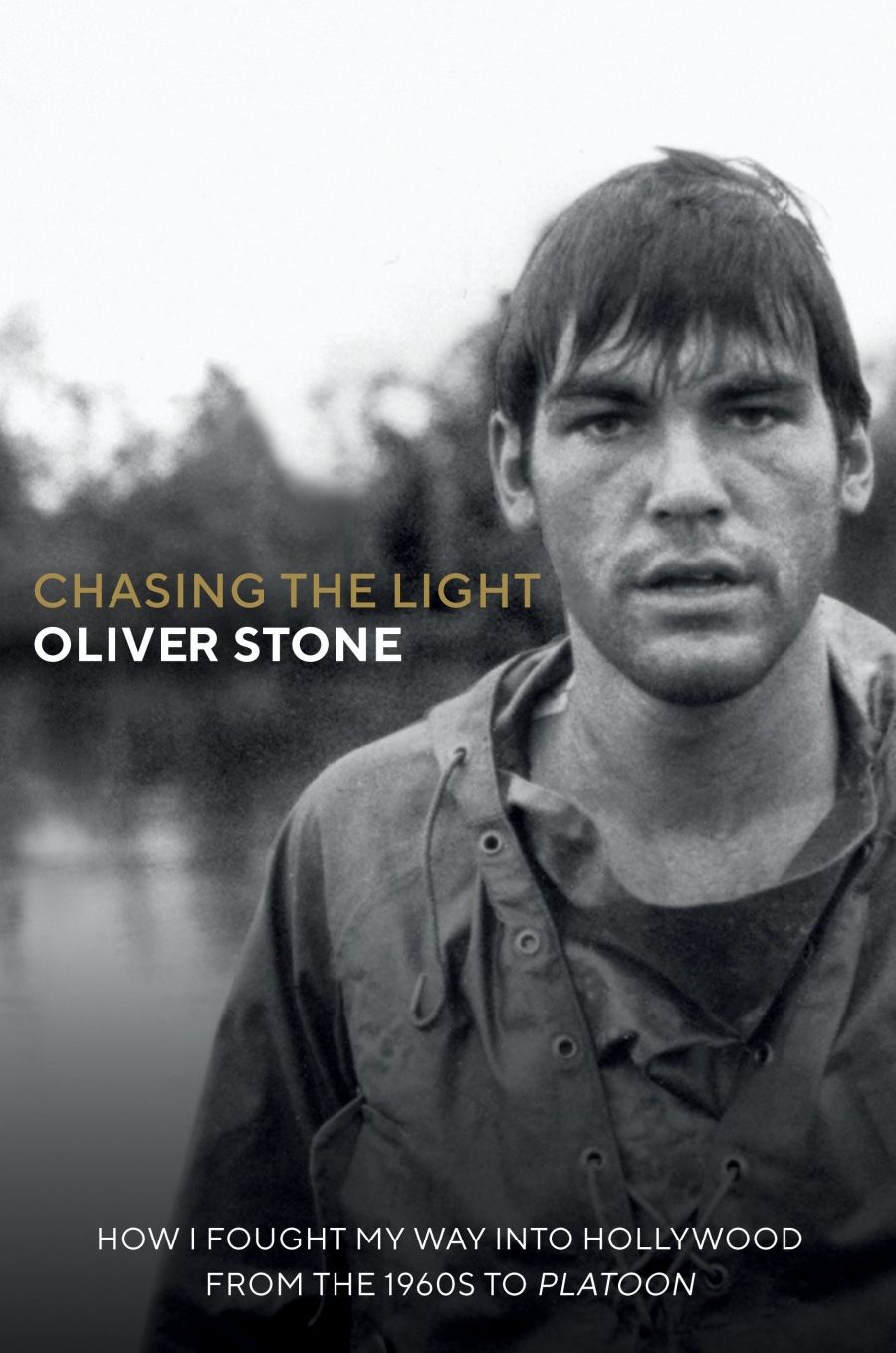

- Book 1 Title: Chasing the Light

- Book 1 Subtitle: How I fought my way into Hollywood: From the 1960s to Platoon

- Book 1 Biblio: Monoray, $35 pb, 342 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/qRnob

Stone evidently admires the rebel-hero figure, the thorn in the side of the status quo, the teller of untold truths and revealer of inconvenient secrets. By creating films he has made himself into a unique brand of counter-diplomat, challenging US propaganda by spinning it otherwise, howling against American exceptionalism at twenty-four frames per second. But just as frequently, this self-styled leftism, with all its sympathies for the plight of global communism, all its solidarity with those countries run over by US foreign policy, reveals itself ambiguously in regard to the power of collectivism. Perhaps it is the role of director that puts him at odds with it, but so does his fetish for the heroic rebel-transgressor. While Chasing the Light leaves no question as to Stone’s distaste for Reaganism, for neoliberal, market-driven economics, it fails to consider how the political economy of his own films is of a piece with them. In the first pages of the introduction, he recounts how he and his crew abandoned Mexico, the shooting location of Salvador, with local creditors and unpaid craftsmen in their wake. The details of how and when these debts were paid are of less import than Stone’s nascent self-mythologising, as he becomes the bootstrapping, tireless Ulysses for whom cutting corners, improvising plans, and pushing around cheap labour in ‘shithole’ countries (scare quotes his) are the secrets of his success.

Stone resents his preppy, Manhattan-society adolescence being used against him, but he does himself few favours by setting these narrative facts amid the ‘poverty-is-great-for-creativity’ premise that Chasing the Light peddles. The idealisation of hunger from a man who was born into wealth and will die with it is suspect, no matter how ‘broke’ he was at thirty. Small details in his narrative actually work to cast doubt on the reality of his struggle. In a tellingly passing mention, he reveals that during the down-and-out chapters of his life he was already represented by William Morris, the foremost literary agency in the United States. It is easier to fetishise adversity once all the social capital required to overcome it has been accrued. Stone dropped out of Yale before enlisting in the infantry and going to Vietnam, so the question of what kind of student he would have been remains the sort of counterfactual fantasy in which he likes to indulge. Would he have been the anarchist who prides himself on slumming it, two dollars to his name, while conveniently omitting the fact that the opening of a trust or chair on a director’s board awaits him in a few short years? At any rate, such ‘the struggle is real’ shtick from someone unvictimised by a low-wage economy should be served with salt.

As of this year, Stone has all but bowed out of Hollywood filmmaking, with no interest in making another feature. He admits to being unimpressed by the politically correct circus the industry has become, and decries the need for on-location sensitivity counsellors and diverse casting. In a sense, Stone’s stubborn boomer machismo is the most endearing thing about him, letting the outlines of his character show more clearly. At least there he doesn’t trip over his own economic footing the way his left-wing polemics do.

Incidentally, Kael’s review of Salvador was about as close as she came to praising Stone, who, as should now be evident, is a fantastically polarising figure. Responding to her review, even he – as the appeased egoist is like to do – granted her an insight. Kael ‘uncannily sensed the dichotomy in my political mindset’, Stone writes. Perhaps the sensitivities of that critic whom he dubs the ‘Wicked Witch’ were less ‘uncanny’ than he supposes. His self-defeating political mindset is drawn most conspicuously in the casual gestures of this autobiography, voiced as boldly as one of his protagonists might deliver one of their on-the-nose diatribes against US imperialism. The fascination for Stone, no doubt, is in the classical figure he sets out to cut, heroically imperfect. Only so polarising a man could become a representative figure of such a polarised society. The question is: do we need more Stone?

Sure, Chasing the Light makes a worthwhile contribution to the ‘director’s struggle’ subgenre of autobiography, in which Frank Capra’s The Name Above the Title (1971) presides. It adds some vainglorious details to the insider’s tour of New Hollywood, where Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (1998) remains unsurpassed. But Stone’s transgressive hero worship, the Jim Morrison complex he expounds in the middle chapters, is arguably something the twenty-first century could do without. The sexist ‘break-on-through’ moment of the 1960s is increasingly being reassessed as an origin point for the ‘break-things’ libertarianism of late-stage capitalism, not its heroic adversary. Chasing the Light presents an Oliver Stone the world has seen before, not the hero it needs today.

Comments powered by CComment