- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Last spring, as the harbingers of a dangerous season converged into a chorus of forewarning, I decided it might be a good idea to keep a diary of the period now known as ‘Black Summer’. The diary starts in September with landscapes burning in southern Queensland and Brazil. Three hundred thousand people rally across Australia, calling for action on climate change. I attend a forum of emergency managers where, during a discussion about warning systems, a senior fire manager declares: ‘We need to tell the public we cannot help them in the ways they expect, but we’re never going to tell them.’ Next week, Greg Mullins, the former NSW fire and rescue commissioner, comments on ABC radio, ‘We’re going to have fires that I can’t comprehend.’ Federal politicians assure the nation that we are resilient.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

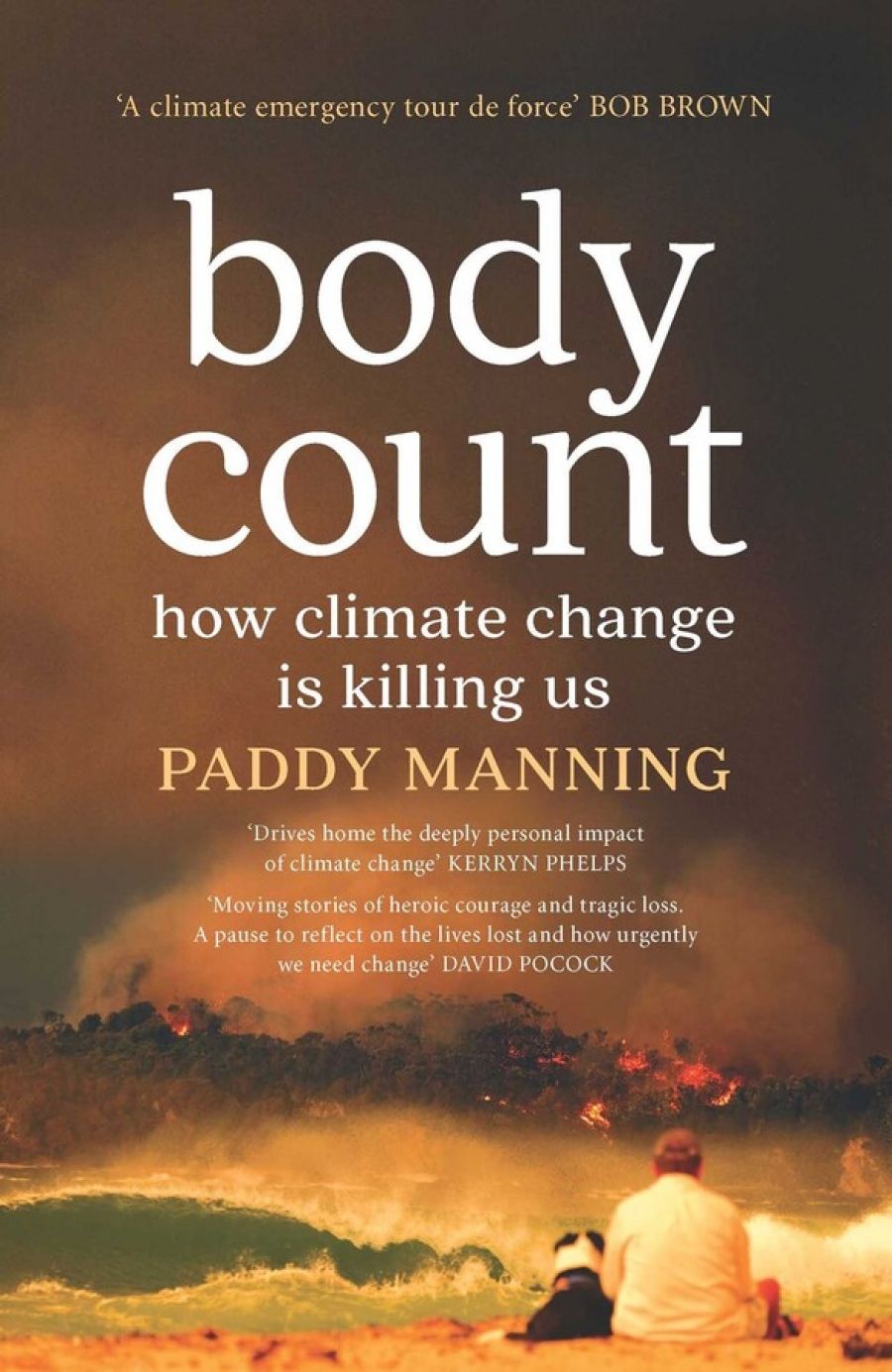

- Book 1 Title: Body Count

- Book 1 Subtitle: How climate change is killing us (Second Edition)

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon & Schuster, $32.99 pb, 349 pp

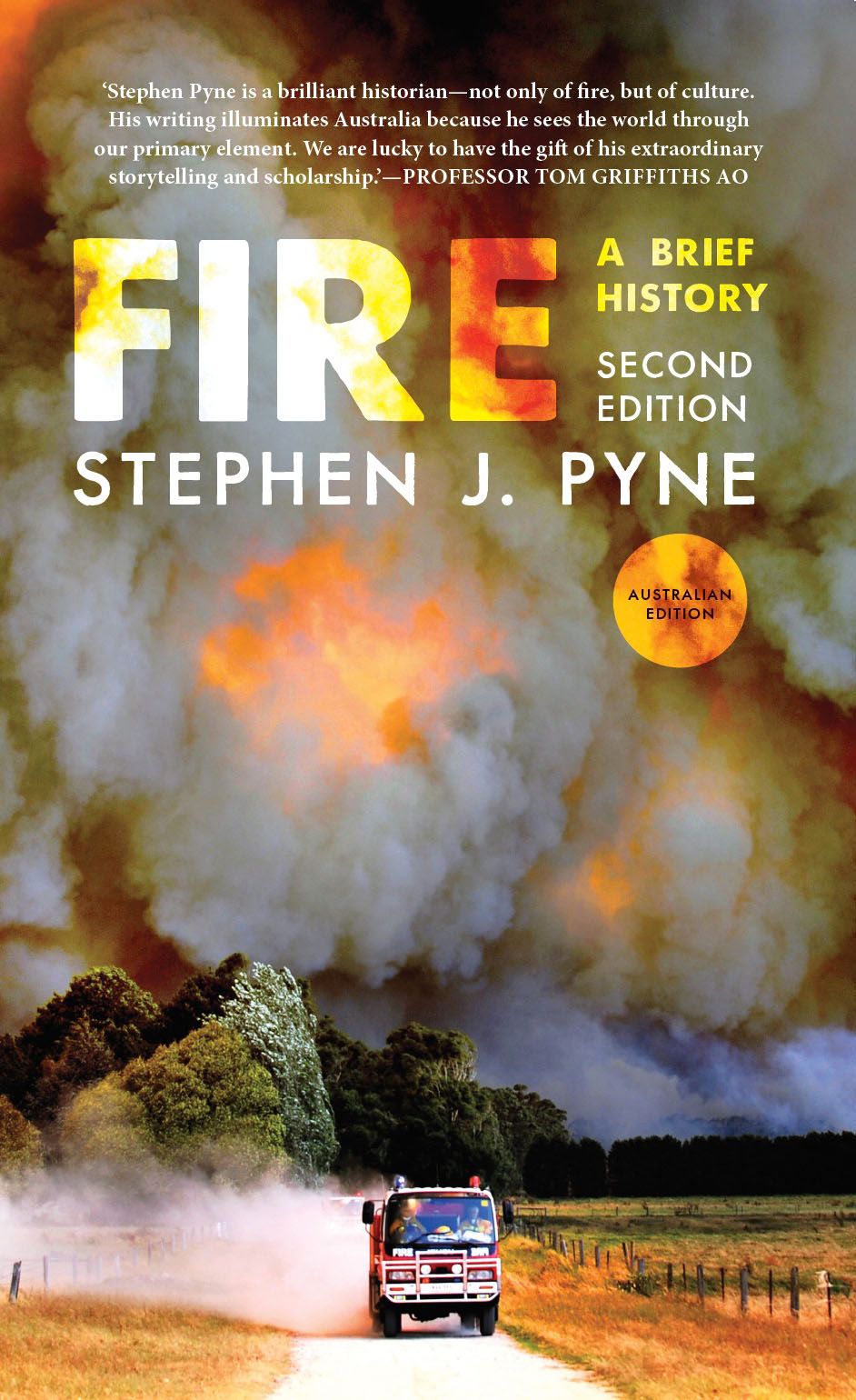

- Book 2 Title: Fire

- Book 2 Subtitle: A brief history

- Book 2 Biblio: NewSouth, $29.99 pb, 238 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_Meta/Sep_2020/META/Fire.jpeg

Black Summer was unprecedented in its length and scale. Just as many predicted its extremity from the biophysical signals, those familiar with past Australian fire crises could have foreseen the archetypical cultural symptoms. There were pitched debates about the timing and wording of warnings and how to manage our flammable bush companions (or ‘fuel loads’). The financially interested offered technological solutions both old (large air tankers) and new (cube satellites), without any mention of their proven efficacy. Politicians, somehow perplexed, commissioned new inquiries to look into the recommendations of the fifty or so inquiries held in past two decades. As in previous fire disasters, these contests were epiphenomena of our differing expectations: that is, expectations about our natural surrounds and our personal safety.

In Body Count, journalist Paddy Manning begins with the 2019–20 fires but extends his horizons beyond, investigating how anthropogenic climate change ‘loaded the dice’ in fatalities due to fire and other hazards such as heatwaves, thunderstorm asthma, and floods. The book is a fair primer on recent disasters but possibly most useful to posterity as a collection of expectations rather than as an analysis. Manning states that we need to properly understand why these people died, but his interviews with their relations uncover few who agree with him about the urgency of climate change or even its very existence.

While one refrain throughout these conversations is people’s lack of trust in government institutions, the most prevalent theme is: ‘Where was the government?’ Why did governments not warn people, or warn them more urgently? Why did the state fail to protect them? The paradoxical coexistence of low opinion and high expectation of government seems linked to a wider sense of stolen safety. Although few of Manning’s interlocutors seem to share his view that climate change entails ‘the loss of a safe planet to live on’, one in which fossil-fuel consumption has turned the climate against us, they all seem to understand that they once lived in secure and certain surrounds.

These surrounds seem very different in Stephen J. Pyne’s revised edition of Fire: A brief history, originally published in 2001, which begins its account of the sticky relationship between humanity and its habitat with the Carboniferous period some 350 million years ago. Only then did Earth’s atmosphere and environs allow a spark to become a flame. Pyne, often presented as the pre-eminent historian of fire, tracks the multitude of ways in which humans have used fire to shape their surrounds, whether through the creation of the hearth, burning landscapes, or the capturing of its power for warfare and energy. His style, which has won him many readers, is overwhelmingly cast in mixed metaphors, binaries, and the archetypes of Greek, Roman, and Christian literature. Unlike Manning, though, Pyne tells a story that is less Paradise Lost than Prometheus Unbound.

This Promethean narrative begins with humans, somewhere around 1.2 million years ago, beginning to harness fires started by lightning strikes and, later, fire-making tools. The raw became cooked. Fires were set to clear ground or set game to flight. With time, it became a means to contour the landscape and its ecologies. A hazardous fire planet, either hostile or indifferent to our presence, became slightly more habitable through hominids’ lasting ‘alliance’ with fire, as repeated burning of certain landscapes made them at once more productive and more combustive. On the Australian continent, as Aboriginal peoples worked with the shifting rhythms of Country, many species that tolerated or even promoted fire flourished.

Readers looking for a detailed account of Australian bushfires might want to start elsewhere, as Pyne’s temporal and spatial scope here is global. Like Heraclitus, the author casts all of existence in fire’s light. Such a claim to primacy is daring and unsatisfying. Just as bushfire management today figures all biomass as fuel, everything is fuel for Pyne’s stadial narrative of humans, who first make a primeval connection with fire and are then alienated from it through forges, kilns, steam engines, batteries, and other ‘pyrotechnologies’. The cost of modernity, in this telling, is that landscapes civilised by millennia of deliberate burning have grown ‘feral’ and have promoted ‘bad fires’.

In the new preface and closing chapter, Pyne suggests that what is needed on a planet experiencing a ‘Pyrocene’ of increasingly frequent and extreme ‘bad fires’ is more ‘good fires’ or preventative and strategic intentional burning. At the same time, he argues, the fixation with fire problems as biophysical matters with biophysical solutions needs to be jettisoned in favour of regarding them as ‘fundamentally a social and political issue’. I fiercely agree, but it’s confusing coming from Pyne, whose books are oblivious to the workings of political power, race, class, or gender.

Such obliviousness is possibly a function of the grand scale of Fire, as the particularities of nations and inequities are always hard to pick out when you’re working with geological epochs. Nonetheless, humanity in general isn’t responsible for a heating planet: it was the work of specific profiteers and colonisers. Repeatedly framing Australia’s post-invasion history in terms of the firestick being ‘passed from group to group’ – rather than in terms of settlers’ aggression and Indigenous dispossession – does not read as naïve simplification. Instead, it seems antipathetic to the arguments made by many Indigenous peoples in Australia that their relationships with fire are matters not simply of technique but rather of restoring ancestral control and authority.

Manning does not seek answers in ancient elemental connections or even redistributions of power, but rather closes with a hodgepodge of social science and nationalism. If Australians are resilient and pull together in an emergency, as we heard from Morrison and others last summer, why not utilise this instinct to combat the climate emergency? And if it is widely accepted that warnings and advice about natural hazards change behaviour and action, as Manning contends, why don’t we mobilise this power to nudge people into taking climate action?

Only, these premises do not withstand scrutiny. First, tales of mateship in a crisis need to be tempered with reminders, offered in abundance by the current pandemic, that the bonds of community are not on offer to all in need, nor do they hold up well under a crisis that lasts more than a few weeks. Decades of action are needed to mitigate climate change. Second, we may know how to promote risk awareness, but we know little about how to translate awareness into action. Instead, it seems to me that the stronger case for better warnings – whether regarding climate change or natural hazards – is the one based on democratic value. The primary rationale for releasing clear information should not be that it will make people do what we want.

There is an aphorism common among geographers and others that ‘there is no such thing as a natural disaster’. Rather, there are normal accidents and slow emergencies in a world accustomed to privatising profit, where individuals are routinely subject to consequences for which they rarely bear anything close to individual responsibility. In such a context, we do not need a new technical fix. We do not need to militarise emergency management. We do not need reminders that we are resilient.

What we do need is to think hard about what we may reasonably expect from life on this combustible planet and why, time after time, some hazards and exposures are deemed natural and others simply ‘bad luck’.

Comments powered by CComment