- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Classics

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Greek myths are entirely predictable: Actaeon offends Artemis and is hunted down by his own hounds; Pentheus refuses to worship Dionysus and is ripped apart by his mother; Antigone disobeys the king, and dies for her crime. Beginning, middle, and end: so familiar, so inevitable. The trick was never really in the plot, but in what you did with it. And what Helen Morales does with Greek myth deserves our fullest attention.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

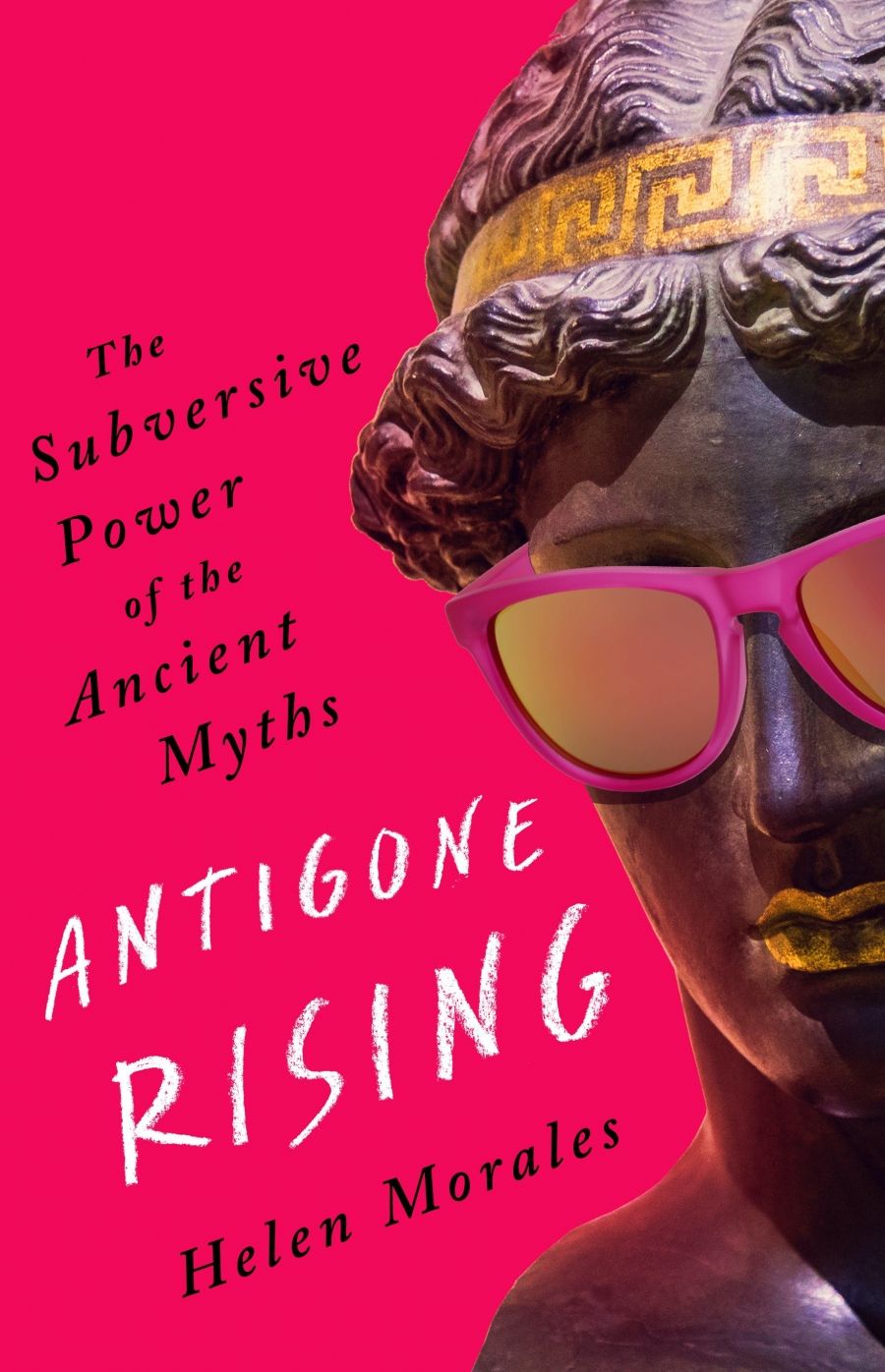

- Book 1 Title: Antigone Rising

- Book 1 Subtitle: The subversive power of the ancient myths

- Book 1 Biblio: Wildfire, $32.99 pb, 222 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/AzoGJ

Morales wears her subjectivity on her sleeve: these are the observations of someone whose life as a mother and educator does not end when she enters the ancient storyworld. Her skill is in bridging those myriad points where the personal and the political, the ancient and the modern, the scholar and the citizen, intersect without resorting lazily to far-fetched analogies or creaky tropes.

The first two-thirds of the book offers a confronting vision of the dark power of antiquity. It asks why stories of heroes killing Amazons were so attractive, why we turn to ancient maxims for diet advice, why Pentheus obsessed over what Bacchants (don’t) wear, why sex-striking Lysistrata stills stands as a paradigm of female activism, and vengeful Diana represents female empowerment. For Morales, the danger lies not merely in their cleaving to the normativity of the basic templates, but in their suppression of potential alternatives. A sex strike to end Liberia’s civil war garnered headlines and mouse clicks, but such reporting reduced the women involved to mere domestic objects. Overlooked entirely in the crass details is the real work of sustaining activism and a whole landscape of political principles and progress. Leymah Gbowee describes three years of community organising: ‘the greatest weapons of the Liberian women’s movement were moral clarity, persistence, and patience’. Sex, in other words, was the least of their arsenal. Likewise, ‘Diana, Hunter of Bus Drivers’, responsible for a pair of murders claimed to be in retaliation for the sexual violence suffered by women in Juárez, takes on the folkloric glamour of the huntress-goddess. Yet, as Morales points out, this is not real power: glorification of individual acts of violent revenge occludes a bigger story: the crushing catastrophe of a system of justice closed to marginalised and abused women. Indeed, in a chapter cannily titled #Metu, Morales shines a light onto Ovid’s repetitive, recognisable, inevitable emplotment of gods raping vulnerable heroines. With this as our familiar template, no wonder we struggle when real women come forward to detail the actual, messy traumas of sexual assault.

The book offers a confronting vision The book offers a confronting vision of the dark power of antiquity

Rare indeed are those Greek heroines who are able to band together: collective action falters when the plots are repeatedly stacked against you. Morales’s dea ex machina is neither Diana, nor even the Antigone of the title, but Beyoncé. Her turn in the Louvre is the turn the book needs, proof positive that ‘it takes a cultural phenomenon to rewrite a cultural script’. Morales juxtaposes here the bland, superficial certitude of white supremacist appropriations of antiquity with the layered, shifting juxtapositions of the ‘APES**T’ music video. As the Carters sing ‘I can’t believe we made it’, Morales takes us in new directions: to museum collections dominated by European ideals of beauty but blind to the actual sources of their imperial wealth, to the mirage of a ‘Greek miracle’ in a Mediterranean already indebted to the millennia-old innovations on its southern and eastern shores, to marble statues that were not originally white, and to the very idea of taking up space to protest and to find newness in revivifying the past. It is a statement about the exclusion of Black bodies that is simultaneously ‘restorative mythmaking’.

The ‘subversive power’ of Morales’s title lies ultimately in our hands. Nuance and complexity are products of thoughtful, committed engagement: ‘the viewer makes connections’. Woven through the book is an argument so old that it is again revolutionary: an argument for the best that philology can offer. This is a book founded on deep reading, close analysis, and decades of teaching and studying. Ancient literature is not a prestigious straitjacket or a canon to be learned and recited, but a jumping-off point, a place of inspiration as weird and as varied as the present. So, when Beyoncé plays Venus pregnant, Morales muses that for all her defying of recent convention, she is recalling the Roman mater who gave birth to Aeneas. The Liberian activists take us back to Lysistrata, where the sex strike is both more cringingly crass – and more serious about economic inequity – than we typically (mis)read it to be. And in seeking a trans experience in a Greek storyworld seemingly so unwelcoming to transgressions of conventional binaries, she finds a fragment from a sixth-century mythographer. Describing how Caenis was raped by Poseidon and became Caeneus, invulnerable warrior, Acusilaus uses male pronouns before the sex change: his male identity was there before the transition.

There is nothing intrinsically exceptional about Greek myths except this: we have been living with them for millennia, and they have the deep patina of objects passed through myriad hands. There is no secret knowledge to be unlocked in them, just, for the patient and the observant, the story of our lives as storytelling animals. In Morales’s telling, the central point of enquiry should not be the tale told, but the teller.

Comments powered by CComment