- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Melburnians above a certain age will remember Coles in Bourke Street. Unknown to most of them, it stood on the site of another Coles, Cole’s Book Arcade, for half a century probably the most famous shop in Australia. Its founder, Edward William Cole, is now the subject of an engaging biography by Richard Broinowski.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

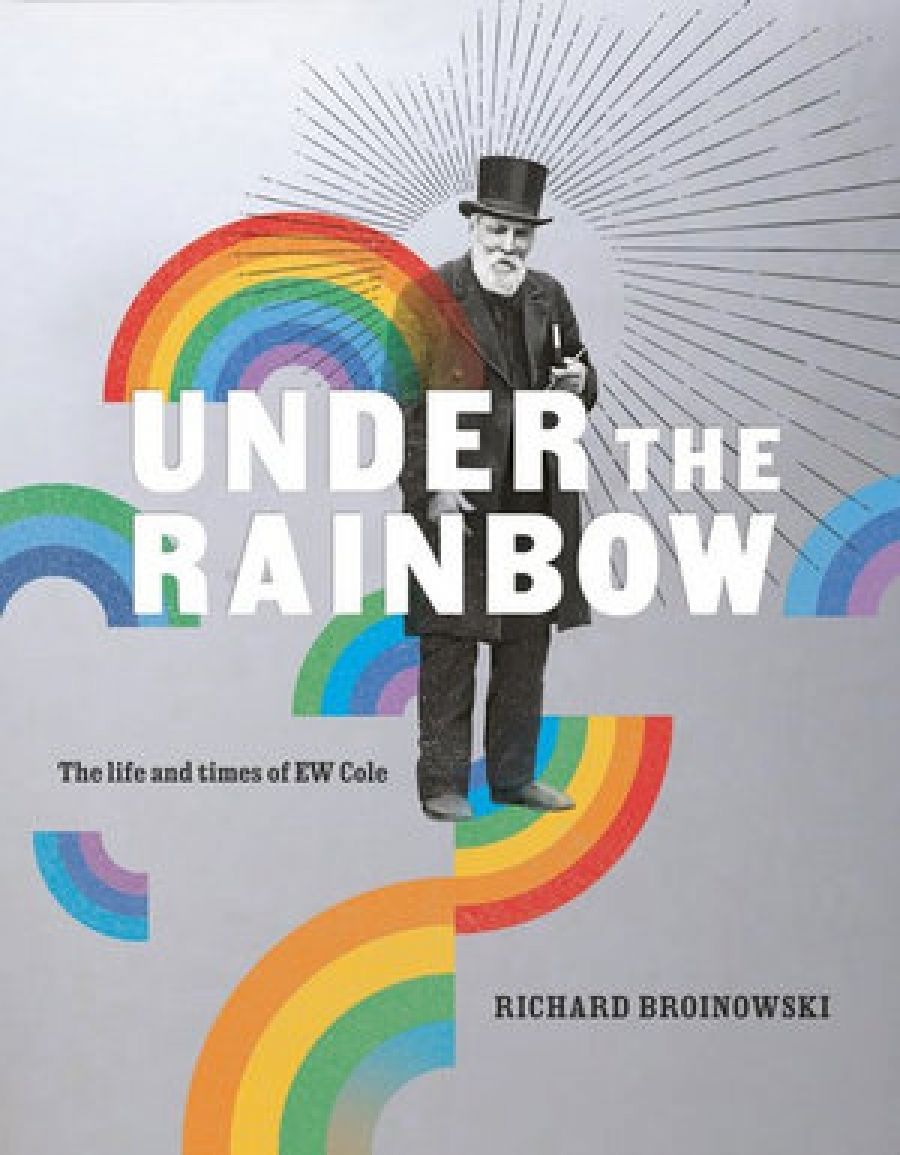

- Book 1 Title: Under the Rainbow

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and times of E.W. Cole

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $44.99 hb, 319 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/jEWBb

He then emigrated to South Africa in 1850. Little is known about the two years he spent there: he went to the Eastern Cape but found it discomforting, as it was embroiled in yet another frontier war. Then Victoria beckoned, as the site of recent gold discoveries. Cole crossed the ocean, made his way to Castlemaine, and soon realised that, compared with the hit-and-miss of prospecting, real money was to be made by supplying miners’ needs. He began by making lemonade, but, being both curious and progressive, he pioneered photography in the district; later he went on a four-month trip down the Murray with his business partner, producing stereoscopic photographs. Back in Castlemaine, other business ventures foundered. Bankrupt, Cole retreated to Melbourne, living on his wits. He opened a pie stall in the Eastern Market; a woman offered him some books she no longer wanted. He thought he might as well take them, and placed them alongside the pies. They sold (you might say) like hot cakes. Cole had found his vocation.

E.W. Cole in his study at the Bourke Street Arcade

E.W. Cole in his study at the Bourke Street Arcade

He established a bookshop, then in 1883 opened the Arcade that made him famous. Entered under the large painted rainbow Cole adopted as his trademark, the establishment rose a full three storeys; instead of dowdiness, light streamed in from the plate-glass ceiling. Galleries full of books lined the walls. Counters were generally absent; people were encouraged to help themselves. ‘Read the books. No-one asked to buy.’ One of the many to avail himself of Cole’s invitation was R.G. Menzies, then a poor law student. Cole provided seats – public seating was unavailable, then – greenery, and even a fernery. Children were entranced by gadgets, parrots, and particularly the monkeys (ultimately removed after outraging public decency). Adults were soothed by the strains of a small orchestra, playing light classics (stiffened by a popular hymn). There was something for everyone. More and more features were added until the place became a protodepartment store: fancy goods, porcelain, photography, and framing were all on show – along with such delights as a mechanical hen, laying metal eggs. Outliers of the Arcade eventually extended to Collins Street and Howey Place.

Edward Cole was an avid publicist and knew how to grab attention. A series of newspaper advertisements told of an extraordinary tribe recently ‘discovered’ in mysterious New Guinea. The people had tails. It became a running gag, even after people saw that their name, the Elocweans, was really E.W. Cole spelt backwards. Cole also produced tokens and medals. Then there was Cole’s Funny Picture Book, immediately recognisable by the trademark rainbow on a black background: ‘a richly grotesque collection of Victoriana’, Broinowski writes. It was a kind of scrapbook, containing stories, rhymes, riddles, moral and uplifting tales, poems, and cartoons, including one of a Patent Whipping Machine for Naughty Boys, which was half-serious. First published in 1879, Cole’s Funny Picture Book became a familiar object in many a household: it sold 870,000 copies and was last printed in the 1960s.

Cole’s most extraordinary act of publicity was when, in all seriousness, he advertised for a suitable wife. He listed the (conventional) virtues and attributes he required, and – even more remarkably – found her. His marriage to Eliza was happy, fruitful, and long-lasting.

Cole was doubly Victorian, both a man of his place and of his era. For a man with only a smattering of education, he was also, as Broinowski points out, ‘slightly ahead of his time’. He might have fantasised about a flying machine propelled by umbrellas, but he had a genuine interest in aviation. He believed in world federation and the universal use of a modified English. Having been struck, on that journey down the Murray, by some deep similarities between Aboriginal beliefs and Christianity, Cole was also strongly opposed to all sectarianism. Instead he asserted, ‘Advance knowledge. Let prejudice perish, let justice and charity encircle the Earth and extend to the men of every creed.’ More simply he would say, ‘Do good and you will be happy – and make others happy.’ He wrote pamphlets, annoying the clergy and respectables. For them he had an additional word, as – without racial prejudice himself – he came to campaign against the White Australia policy. How can you support this policy and call yourselves Christians? he asked. Don’t you realise Christ was a coloured man?

Under the Rainbow has been generously conceived. Apart from the well-written narrative, there are discursive boxes giving fuller treatment of particular subjects. The book has been carefully researched, overseas as well as in Australia, particularly with regard to Cole’s Japanese connection.

It also pays attention to his origins, deconstructing family stories, and to his sad decline – when employees at the Arcade would refer to him and his colonnaded mansion derisively as ‘the Parthenon’. And Broinowksi has been served well by his publisher, Melbourne University Publishing, which has drawn on the Miegunyah Fund for a sumptuous production. Illustrations are lavish and pertinent, from street scenes to a collection of Cole’s tokens, and the mechanical hen. The sense of display echoes the famous arcade itself.

Comments powered by CComment