- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Alex Miller first thought of writing about Max Blatt, he imagined a celebration of his life. But would Max have wanted that? He was a melancholy, chainsmoking European migrant, quiet and self-effacing, who claimed nothing for himself except defeat and futility.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

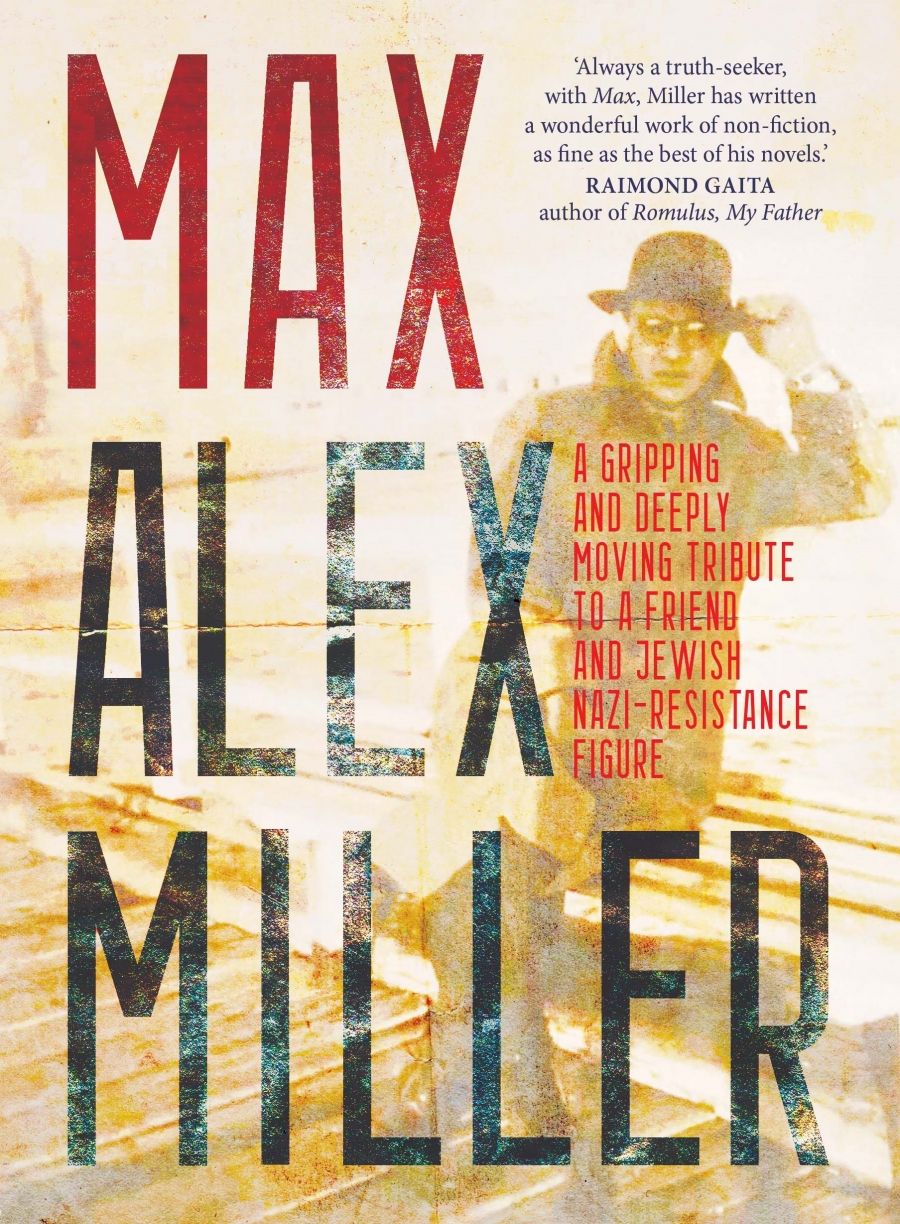

- Book 1 Title: Max

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 280 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/35PoM

For all their closeness and rapport, some part of Max remained forever a mystery. He was a man given to silences who revealed little about his past. Miller knew he had been a communist resistance figure in Nazi Germany and that in 1933 the Gestapo had imprisoned and tortured him. He guessed that this was the reason why something seemed broken in Max: realising that his torturer was his brother, so to speak, he lost his faith in humanity and his whole life began to seem futile to him.

After Max’s death, something slowly stirred in Miller: a desire to rediscover his mentor’s life and to write about it. He is candid about the reasons. One is a sense of guilt: Miller didn’t contact his best friend in the two years before he died, and he doesn’t know why. Another is a conviction that, although he never asked, Max would have wanted his friend to tell his story. Still another is that Miller would like to bolster his sense of Max as a hero and prove that Max was wrong: his life did matter. Along with the desire comes tension and fear. Who knows what he will discover?

Max, a non-fiction book, is not in fact the story of Miller’s friend. Such a story could never be complete – it exists only in fragments. What it is instead is a long, deeply absorbing and moving detective story, with Miller as the detective trying to track down the elusive traces of his friend. The trail meanders through old documents, letters, photographs, and background histories of the times, and takes Miller and his wife, Stephanie, to Germany, Poland, and Israel.

Nothing goes smoothly: Miller encounters constant setbacks, surprises, dead ends, and maddeningly incomplete information. For a start, Max Blatt does not seem to be his hero’s real name. And yet it’s striking how both dogged persistence and sheer chance produce results – above all, through the people Miller meets. This is no dry and dusty quest through the archives: at every turn, someone spontaneously materialises to help him through sheer curiosity, empathy, and generosity of spirit. The book is full of his vivid tributes to these people.

The trail flows backward to more than one source, branching out into many tributaries that are all important to Max’s story. Perhaps naïvely, Miller began his quest with the conviction that he would not have to delve into Holocaust history. The reader suspects this cannot be true when examining the life of a Jewish resistance figure living in Europe in the 1930s. Olek, one of Miller’s contacts, who is today keeping the traditions of Judaism alive in Poland, never knew Max but made a shrewd guess about him. Something decisive must have happened in his life, ‘something of which he was not proud’.

Miller discovers that ‘something’, which has everything to do with family and survivor guilt. In 1940, when Max was living in Poland, he made the necessary but wrenching decision to escape into Lithuania, then made his way to Shanghai and finally to Australia. What he left behind must have haunted him all his life. His conflicted feelings come over powerfully in Miller’s account of Max meeting his brother Martin at the airport in Tel Aviv after thirty years of separation. They stood on the tarmac and gazed at each other for half an hour before they embraced. ‘There were, and there are, no words for it,’ Miller writes.

Somehow, though, he finds the right words. Highlights of this book are the enchanting vignettes Miller gives us of places he finds in the course of his travels, places that offer a fleeting tranquillity and beauty we can set with some relief against the darkness of his discoveries. He observes the innocent faces of fox cubs, or an old hand pump freshly painted green, or he romps with an old friend in the grey Sea of Galilee. All these seemingly disconnected interludes become magical parts of the search for Max.

Another surprising pleasure is Miller’s discovery that often the facts in the story matter a good deal less than the myths that friends, families, and descendants create, memories that may not be reliably or objectively true but still carry their own poetic and spiritual authenticity and significance. Which is no doubt why Miller also makes a point of telling us about his dreams.

There are many things we will never know about Max, but he lives on in the hearts of those who loved him. In Miller’s account, these include some women, particularly Liat, Martin’s daughter and Max’s niece. Miller first met her when she was fifteen at Max’s house in Melbourne, but he has no recollection of her. It is the elaborate trail of research that leads him to Liat in her sixties, running a farm in Israel, her warmth and generosity perfectly expressed in their picnic by the Sea of Galilee, where she serves tea and pieces of cake on a plate rimmed with pink roses.

In its solemn fashion, Max is indeed a celebration of Max Blatt’s life: or, more accurately, a celebration of the way that he is remembered, with all the inevitable gaps and imperfections, in the lives of those who follow him, and those who have been drawn together through Miller’s quest.

Comments powered by CComment