- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Miles Franklin used to delight in relating an anecdote about a librarian friend who, when asked why a less competent colleague was paid more, replied succinctly: ‘He has the genital organs of the male; they’re not used in library work, but men are paid more for having them.’

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

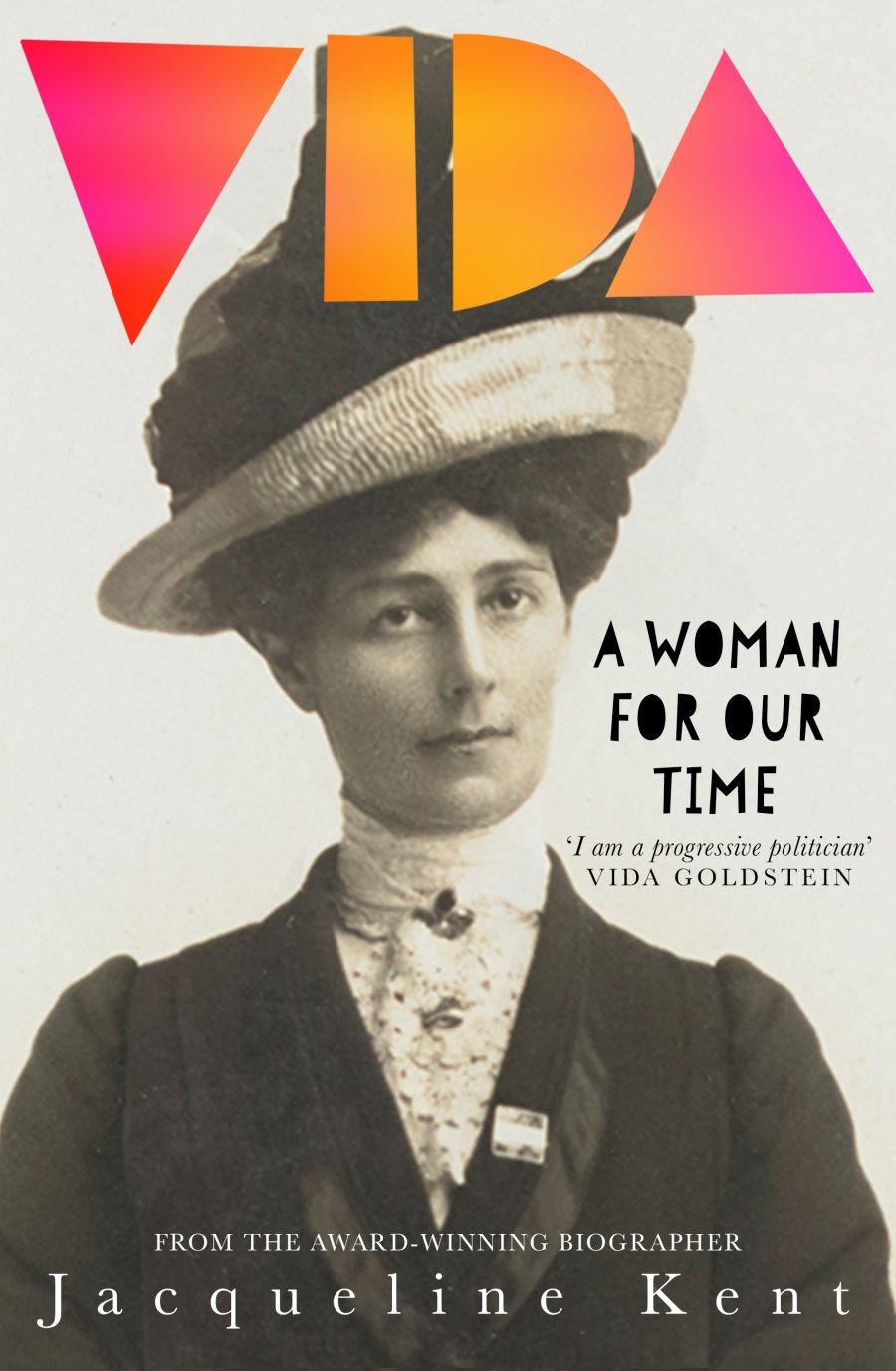

- Book 1 Title: Vida

- Book 1 Subtitle: A woman for our time

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $34.99 pb, 329 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/bZ3Nk

Starting her public life as a suffrage activist, Goldstein (1869–1949) made her first bid for federal politics in 1903, standing as an independent candidate for the Senate on a platform of women’s rights. Unsuccessful, she was ranked fifteenth of eighteen candidates, but outpolled each of the other two women candidates by more than thirty thousand votes. Goldstein was to make four more attempts to win a seat in parliament, the last and least successful being in 1917 when her increasingly militant support of the suffragettes and her pacifism during wartime dented her popularity. Disillusioned but not embittered, she continued to work for social reform and devoted the rest of her life to the Christian Science faith that had helped her bear the acrimony she received from both public and press. Throughout, she was supported by her loyal cohort of Women’s Political Association (WPA) members who managed her campaigns, spoke at rallies, and wrote for the Woman Voter, a situation that might be envied by recent female leaders like Julia Gillard, who not only had to contend with public opposition but also with the factional interests of the men in her own party.

A woman of international standing who charmed President Theodore Roosevelt in America in 1902 and addressed an enthralled audience of ten thousand in London as a guest of the Women’s Social and Political Union in 1911, Goldstein is not widely remembered today, although Clare Wright’s portrayal of her in You Daughters of Freedom (Text Publishing, 2018) has helped shed new light. Her obscurity is in part due to her reserved nature and equable temperament; the woman behind the immaculate presentation and apparent lack of intimate relationships has remained a mystery. For Wright, she was ‘a public woman’ who ‘lived and breathed politics’.

Jacqueline Kent, well placed as a biographer of Julia Gillard, has taken up the challenge to breathe life into this earlier political woman. In an interview in 2019 when she was writing Vida, Kent vowed to ‘go a bit deeper’ than the previous concentration on her public career, ‘to join dots, sometimes even to speculate’. Kent draws extensively on the archival research undertaken by Goldstein’s first biographer, Janette M. Bomford, whose book That Dangerous and Persuasive Woman: Vida Goldstein (Melbourne University Press, 1993) laid out Goldstein’s career in almost forensic detail. On this basis, Kent builds a more comprehensive picture of Goldstein’s family life, including her quietly progressive social reformist mother (only nineteen years her senior) and her more domineering, anti-suffragist father, who remained under the same roof even when the couple became estranged. A chilling detail in the story of her maternal grandparents may have influenced Goldstein’s concern for women’s marital rights and her lifelong temperance.

One less successful speculation concerns the ‘conjecture’ around Goldstein’s friendship with her dynamic business manager, Cecilia John, who burst onto the WPA scene in 1913, alienating some of the more moderate feminists. The two worked closely over the next few years, forming and running the Women’s Peace Army together and eventually representing the WPA at the International Congress of Women’s conference in Zurich in 1919, after which they parted company. A more nuanced reading might have done more than repeat the rather stale argument about women’s intense friendships, after which the discussion is closed off with the ahistorical statement: ‘Vida never identified as lesbian, although Cecilia John did.’ To my knowledge, Cecilia never ‘identified as lesbian’, nor did other WPA women in same-sex relationships such as Mary Fullerton and Mabel Singleton, who distanced themselves from a term then considered synonymous with perversion. Goldstein remained silent on the subject of desires she may have harboured, either for Cecilia or for the unidentified men who made the many marriage proposals stressed by both Kent and Wright. (Curiously, Kent never couples the two women’s first names, referring to them as ‘Vida and Cecilia John’ or ‘Vida and John’, a distancing practice that gives rise to such oddities as ‘Vida, John and Adela’.)

The main strengths of Vida lie in its contextualising of the time, from ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ of the 1880s to the economic depression of the 1890s to the rigours of the World War I years and later, and also in Kent’s elucidation of the wider political scene, particularly when she compares Goldstein’s position with today’s Australian female politicians. Differences as well as similarities between the periods are noted: the WPA’s racism and support of the White Australia policy, for instance, and the essentialist view of the suffragists that women in power would provide a purifying influence on men.

Kent’s engaging style, never ponderous or dry, will introduce a new generation of readers to the life and times of an important Australian pioneer for women’s rights. If, despite the promise of the book’s intimate title, the ‘real Vida’ remains somewhat elusive, it is interesting to speculate on possible counterparts in politics today. To my mind, the woman who most resembles Vida Goldstein’s calm and charm, her quick wit and steely-eyed determination, is Penny Wong, even though, unfortunately, she does not aspire to become prime minister. Non-Anglo, a lesbian, and a mother, Wong truly is ‘a woman for our time’.

Comments powered by CComment