- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

From the moment one reads that this book is dedicated ‘To the worm that first gnawed at the cold flesh of my cadaver’, it is clear that The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas, first published in Rio de Janeiro in 1881, is a novel like few others.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

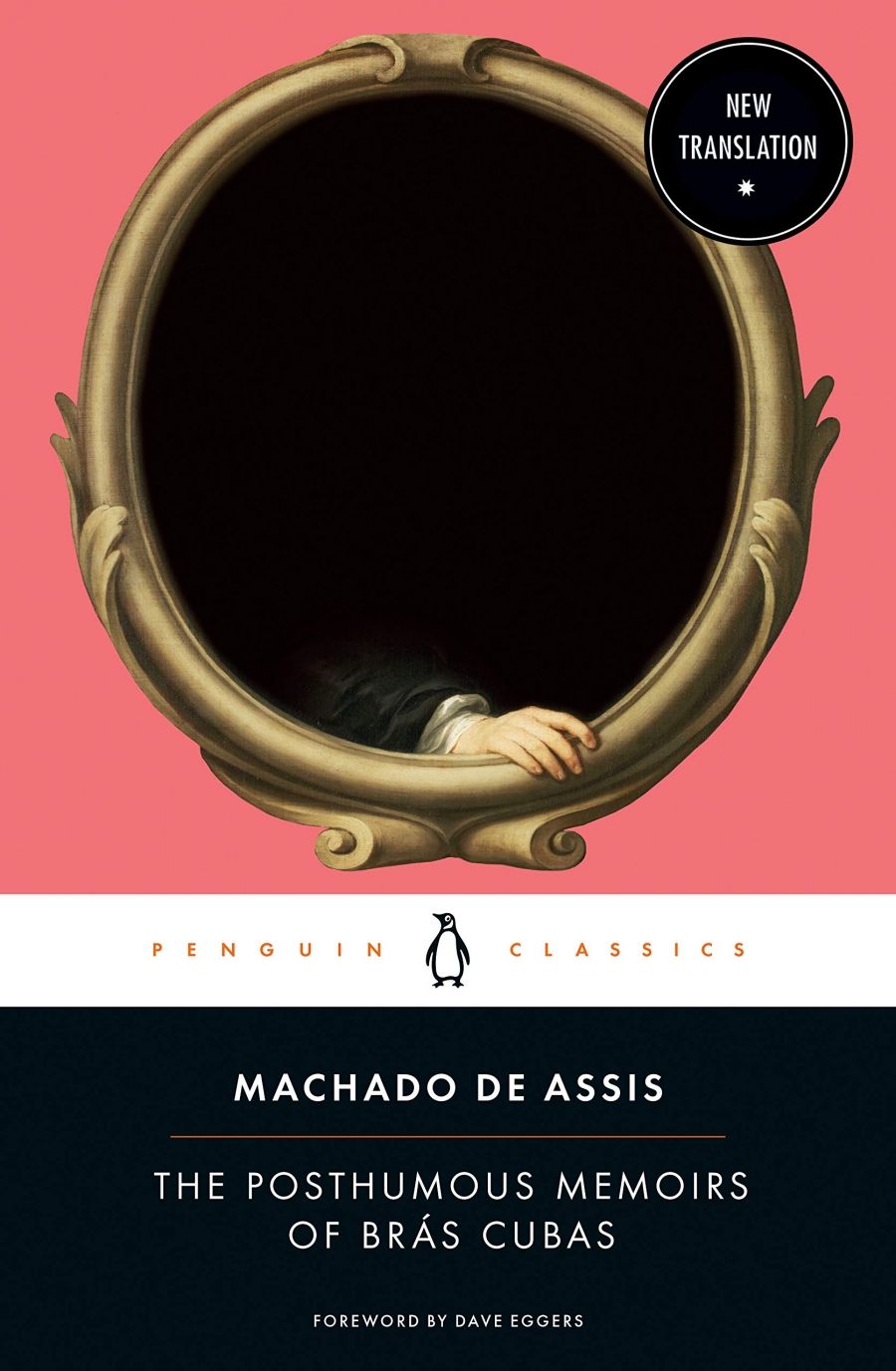

- Book 1 Title: The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin Classics, $27.99 pb, 368 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/xx9kd

Any attempt, however, to reduce this novel to a plot summary does it a tremendous disservice. In telling his life story, Brás takes the reader on a journey from the Garden of Eden to the fall of Napoleon, via meditations on the pleasure of removing tight shoes, the metaphysical purpose of the human nose, and the 1848 Dalmatian Revolution, at one point riding through ‘the living condensation of all time’ on the back of a taciturn hippopotamus. One chapter consists entirely of punctuation; another is simply Brás’ notes for a chapter he never writes. Chapter 130 is to be inserted into Chapter 129.

As playful as this novel often appears, it is nevertheless a deeply affecting examination of the human condition. Lovers’ thoughts fly across the city and sit conversing on a windowsill; a house where the lovers once hid is later knocked down and replaced by one three times the size, ‘but I swear to you that it is far smaller than the original’; a slave fantasises that his master’s property belongs to him – an illusion that allows him a brief moment of pride and pleasure.

The daily presence of slavery and servitude in this world, which feels more like a tropical Belle-Époque Paris than a colonial outpost, is one of the novel’s most thought-provoking engagements with its discourse, rendered all the more fascinating today by its resonance with contemporary Brazil and the renewed global vigour of civil rights movements.

Machado de Assis, 1904 (Public domain/Arquivo Nacional Collection)

Machado de Assis, 1904 (Public domain/Arquivo Nacional Collection)

Machado de Assis – known generally as Machado – was the mixed-race grandchild of freed slaves. For most of his life, it was legal in Brazil for one human to own another. In his pioneering critical works on Machado, the Brazilian literary and cultural critic Roberto Schwarz examines how the fundamental tensions and contradictions of nineteenth-century Brazil are laid bare in The Posthumous Memoirs. Schwarz describes how Machado’s poetics – especially the volubility of narrators like Brás, who can switch opinions in a heartbeat – manifest the fundamental tensions of a nation that incorporated passages from the Declaration of the Rights of Man in its 1824 constitution, yet clung to legalised slavery until 1888, seven years after the publication of The Posthumous Memoirs. In his ground-breaking 1973 essay on Machado, ‘Misplaced Ideas’, Schwarz contends that the enshrining of these mutually exclusive notions in Brazil served to illuminate the ongoing inequality perpetuated by liberal political systems in Europe and North America in the same period.

Despite being almost 140 years old, this novel feels like it could have been written yesterday. Thomson-DeVeaux’s translation is a significant achievement. It renders Machado’s distinctive prose in a manner that captures the tone and register of the original Portuguese, while her comprehensive introduction and explanatory notes allow the novel to pour beyond the pages into the world at large. The chapter entitled ‘The Whip’, in which the narrator encounters his childhood slave beating another man in the street – ‘he had bought himself a slave and was paying back, with steep interest, the sums he had received from me’ – is powerful enough on its own, but the note explaining the significance of the area in which the scene occurs brings the incident directly into the modern day.

Some notes detail variations between the text as it is presented here – based on the definitive fourth edition of the novel – and its original serialised form; others provide background and context for Machado’s wide-ranging literary and historical references. How one engages with the endnotes, however, is entirely up to the reader: like all great works of universal literature, the novel itself needs no explanation.

Early in the novel, Brás observes: ‘That Stendhal should have confessed to writing one of his novels for only a hundred readers is a source of some surprise and consternation.’ In turn, Brás suggests he would not be surprised if his own memoir fails to find ten readers: ‘Ten? Perhaps five ... But I still harbor hopes of winning the sympathies of [public] opinion.’

That Machado’s oeuvre should have had such difficulty winning the sympathies of English-language readers is almost inexplicable. With Thomson-DeVeaux’s masterful new translation and its widespread accessibility through Penguin Classics, the worm might finally turn.

Comments powered by CComment