- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Malcolm Knox told Kill Your Darlings in 2012 that with The Life (2011), his celebrated surfing novel set on the Gold Coast, he wanted to write a historical novel about the Australian coastline and ‘that moment when one person could live right on the coast on our most treasured waterfront places, and then all of a sudden they couldn’t’. In Bluebird, set on a northern beach a ferry ride from ‘Ocean City’, this brutally undemocratic transformation is promoted from a minor theme to the engine that drives the highbrow soap-opera narrative.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

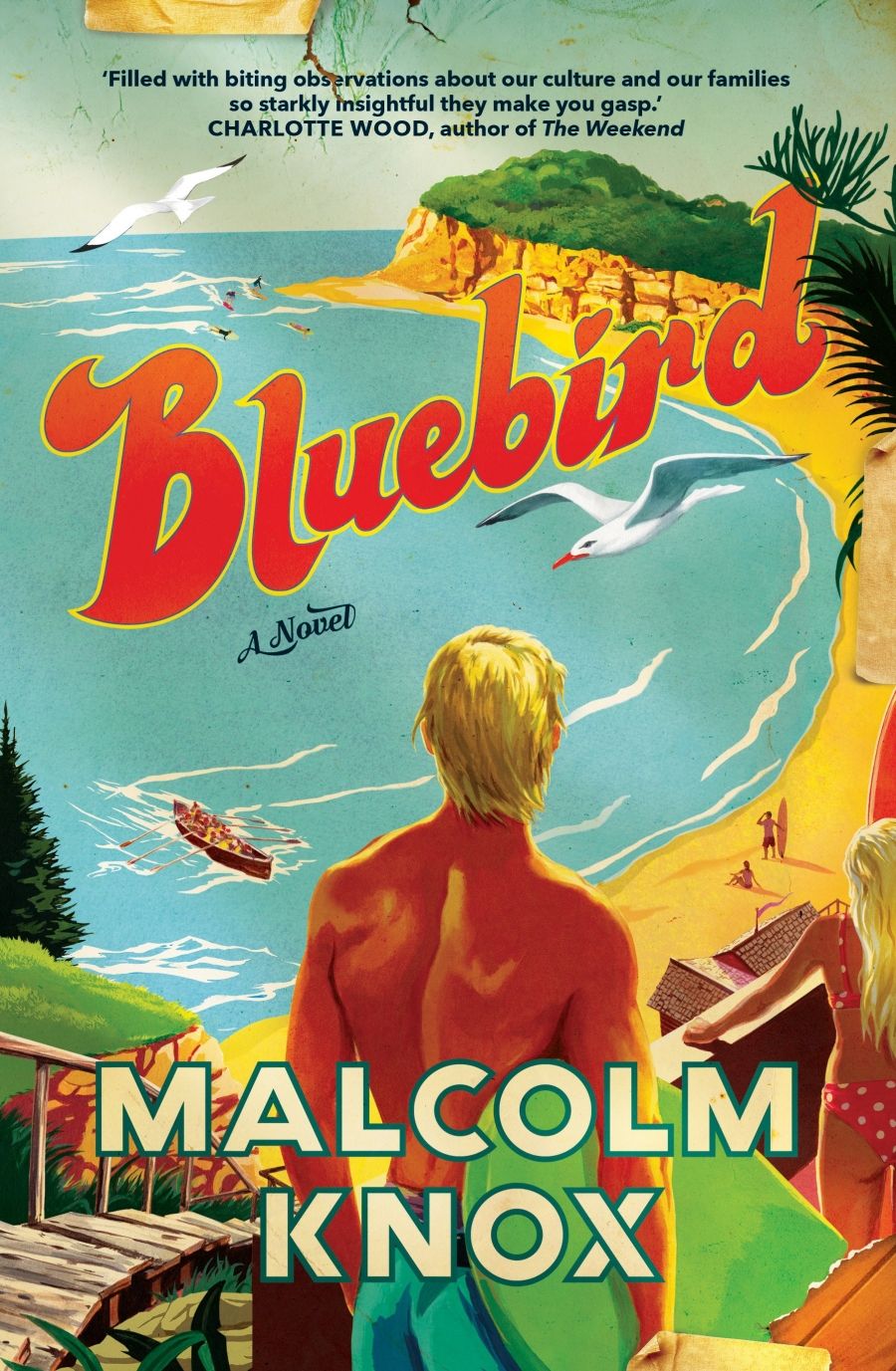

- Book 1 Title: Bluebird

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 487 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/rvnn5

Malcolm Knox (Patrick Cummins/Penguin)

Malcolm Knox (Patrick Cummins/Penguin)

Knox is a past master of contemporary social realism, using carefully mined details of character and place to reveal complex truths about how we live and who we are as a society. His first three novels – Summerland (2000), A Private Man (2004), and Jamaica (2007) – cleverly dissected the mores and subterranean lives of Sydney’s bourgeoisie, with a focus on the sinister undercurrents of relationships that maintain polite veneers. The Life (2011) was a departure in terms of style and subject, with his articulate, cultured, determinedly ‘ordinary’ narrators replaced by a kinetic ocker poetry that reflected the adrenalised waves and spikes of working-class surf champion DK’s interior life. The protagonist of his last novel, The Wonder Lover (2015), was another oddball outsider; this time, hyperarticulate and deliberately stripped of the kinds of defining cultural characteristics so integral to Knox’s earlier social realism. A fable with a magical realist edge, it carried a clear moral warning against living life without fully committing to it; in a theme continued in Bluebird, it showed that failure to act has consequences.

‘Gordon could never have made the hero of a man’s story,’ says Lou. ‘Men’s heroes have motivations to act. Gordon makes excuses not to … All Gordon wants is the status quo.’ In a tragicomic subplot, Gordon refuses to acknowledge Dog’s betrayal, and continues to endure his daily presence rather than confront him. ‘Indifference, a fair go, being laidback, whatever you wanted to call it, was a collective effort mighty in its tenacity,’ reflects Kelly, whom Gordon amiably forgives, and who slept with Dog not out of nostalgic lust but as a clumsy blow against inertia. Gordon’s general inaction, however, is less indifference than a reluctance to disturb a well of repressed emotion; a childhood tragedy at its deepest level. ‘If he let himself go in that direction, he could not say where he would stop.’

Knox’s old Bluebirders are property rich and cash poor. ‘Old Bluebird was a worker’s aristocracy, except for the work part.’ Gordon was retrenched three years ago as editor of the Bluebird News, ‘gone the way of lamplighting, wet nursing and elevator operating’. He’s characteristically unsuited to ‘customer-facing’, which is ‘all that’s left’. Old Bluebirders are marooned in a world that physically resembles their home, though its social conditions have changed, leaving them bewildered and defensive. Leonie, the wicked stepmother archetype, who narrates stylised introductory slivers to the sections of the novel (which read like a meditation over a crystal ball), diagnoses the ‘local infection: crippling nostalgia’.

The irony is that Old Bluebird was a very specific paradise, where racism and homophobia were endemic, and the paedophilia of pillars of the community was silently tolerated. Transitional Bluebird is perhaps best encapsulated by ‘Asperger-ish, ADHD-like’ Ben, whose inability to fit in with the crowd means that he’s punished for falling further outside it with his sexuality. ‘Diversity was cool. Or it was until Ben’s coming-out, which fell flat: someone must have decided they could only take so much, and Ben took them past the unspoken limit.’

This is the first of Knox’s novels to consciously reflect a multicultural, diverse Australia. The racism of the white characters is brilliantly captured through their reactions to characters like Kelly, who is Anglo Indian – particularly Gordon’s mother, Norma. (‘Did it make Norma less racist to utter these comments while not caring about, or even seeing, Kelly’s own colour?’) Leonie is a conscious satire of the stereotype of the scheming, much-younger Asian second wife, which she embodies. But that stereotype is never quite subverted, and though she has a voice, the stylised nature of her interludes mean that she’s never made real or authentic.

At just under 500 pages, Bluebird feels too long. Some ideas are repeated so often that it starts to feel as if we’re being bashed over the head with them – particularly the notion, repeated by several characters, using similar phrasing, that Gordon is dragging down, or ‘killing’, those who try to help him (which only sometimes feels true to the relationship). Despite these structural flaws, at a sentence level Bluebird is consistently excellent, rich with spot-on social observations details that are sharp, funny, and affecting. As a comment on Scott Morrison’s Australia, and an exploration of the casualties and boons of progress, it’s very good.

Comments powered by CComment