- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

John A. Scott’s Shorter Lives is written at an intersection between experimental fiction, biography, and poetry. It inherits aspects of earlier works, such as preoccupations with sex and France. As the title indicates, it narrates mini-biographies of famous writers – Arthur Rimbaud, Virginia Stephen (Woolf), André Breton, and Mina Loy – and one painter – Pablo Picasso – with interludes devoted to the lesser-known poet Charles Cros and the art dealer Ambroise Vollard. The narratives are largely distilled from more conventional prose sources. Scott gives himself poetic licence to fictionalise, and anachronise: Paul Cézanne’s collection of twentieth-century American paintings, for example.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

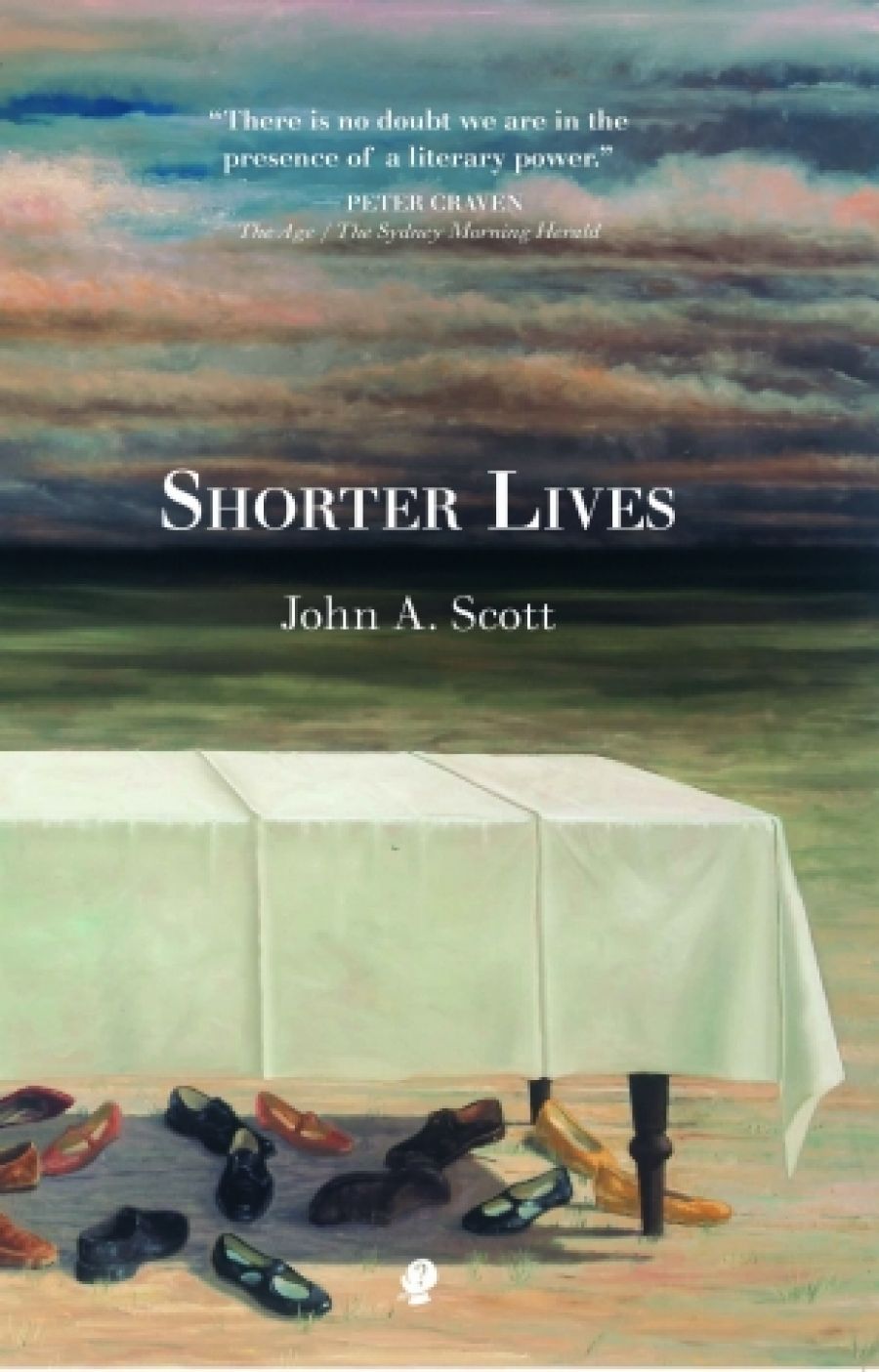

- Book 1 Title: Shorter Lives

- Book 1 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $25 pb, 134 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/q71Kq

The most purely fictional life here is that of Breton: a record of his time spent in Melbourne. The year is 1942, and, after just two-thirds of a page of free verse, a decorative font resembling a circus announcement announces that he has ‘LEFT AMERICA’. From ‘LEFT AMERICA’ on, and, aside from this flourish – and an insertion of Leon Trotsky’s signature, made, mediumistically, in the night, by Breton – this section is in conventionally set prose and reads like a short (nineteen-page) novel. Why leave ‘odious’ America for Melbourne in the middle of World War II? To announce the coming of Ern Malley? (Not exactly.) Breton has been invited by art critic Gino Nibbi. He joins in with the scene at Nibbi’s art shop, the ‘Leonardo’, a scene that includes Sidney Nolan. Also present are (painter David?) ‘Strachan’ and the plausible-sounding ‘Harry Hocking’, a poet who also appears in Scott’s 2014 novel N. Nolan shows Breton photos of ‘revolutionary’ Ned Kelly’s ‘surreal’ armour, which brings Breton to ‘near ecstasy’. What follows is also surreal and involves a conversation in English between Breton and Mr Chang, a Chinese laundry proprietor, regarding the handwritten texts of famous writers who have visited Australia, some fictionally (i.e. Rimbaud) – and others, like Mallarmé, who have not. Chang expatiates on the ‘linen halls’ of laundries, which turn out to be shadow archives, preserving world literature (Ancient Greek and Syrian plays are mentioned): safer than libraries, Chang avers. The figure of Chang, and his discourse, is a brilliant contribution to Australian letters: a figure for Peter Carey to envy (this moment, between Kelly and Malley, feels like Carey territory). Breton, as a poet who represents the manifesto, is the perfect pin to fix this wartime, surreal, and Surrealist-inflected moment. The experience, naturally, raises Australia in Breton’s estimation.

Rimbaud is himself a form by now, even within the context of Australian poetry, but in Scott’s life there is an emphasis on Rimbaud’s body: and also that of Paul Verlaine. The police doctors’ examination of Verlaine’s genitals recalls Michael Jackson’s video statement of his own examination, as legal experiments to see whether their bodies would somehow profess guilt – or humiliation produce confession. Two other aspects are intriguing. The first is the portrayal of Rimbaud’s sister, Isabelle, who sees her brother’s ficto-biographical potential: emerging as a kind of Ethel Malley figure, of whom more could be made. Then there is the posthumous section, which ironises Scott’s title concept, in extending Rimbaud’s shorter life.

Contemporary publishing technology allows for a range of effects, including pages of varied type, which, at one point in Shorter Lives, evokes the archaic, crowded look of nineteenth-century newspapers. Like any retro effect, it is neater than its original. It suggests ‘archive fever’, especially in the researched context of the Stephen family history of madness and abuse. The use of grayscale, used for quotes, but also for the name of Virginia’s sister, Laura, whose clamour/trauma can’t be borne, adds pathos. It is not a quietening device in the same way as the text’s use of smaller type: while clearly legible, it evokes the defocusing effects of contemporary cinema. Despite typographical variation and side notes, this life consists almost entirely of a cycle of sonnets beginning and ending on an indented shorter line, like beads on a necklace.

Forms are envelopes and sonnets are no exception. The Stephen sonnets expel, or sideline, their paratextual notes and quotes, but those of the Loy sequence manage to contain many of theirs – be they paler, of smaller point, of superscript, or of typewriter font. (These sonnets are, in a sense, mongrel texts: mongrel being a key term for Loy, and used throughout this section.) It is the most substantial life: at forty-two pages roughly double that of Rimbaud, Woolf, or Picasso. She is worth the attention, in terms of both work and life. It commences with her relationship with Swiss Surrealist poet Arthur Cravan, the six-foot-seven boxer, a nephew of Oscar Wilde, who famously disappeared, in Mexico, presumably drowned. Given the treatments of Rimbaud and Breton, I wondered if Scott would afford him a new fictional existence? (Not in this book.) Loy goes to a New York party: all the present and referred to are famous, many of whom have Parisian/Surrealist connections; the accumulated network suggests, in Ab Fab terms, ‘Names, names, names!’ It’s almost too readable – if you know the territory. In Scott’s hands, the sonnet (elsewhere mostly a lyric form) seems eminently suited to narrative, although the retelling of Alain-Fournier’s Le Grand Meaulnes, by Loy to the artist Joseph Cornell, one afternoon in her New York apartment, is rendered in prose; but the lyrical, almost-implied discourse of Loy, in sonnet form (in ‘Three Collages’), along with similar moments in the Rimbaud, are for me high points of the book.

The concluding life, of Picasso, is typographically straight. An obvious way to Australianise this narrative would have been to give Picasso an Australian lover – but his sexual relations, as brutally summarised by Scott, we could not wish on anyone.

Comments powered by CComment