- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

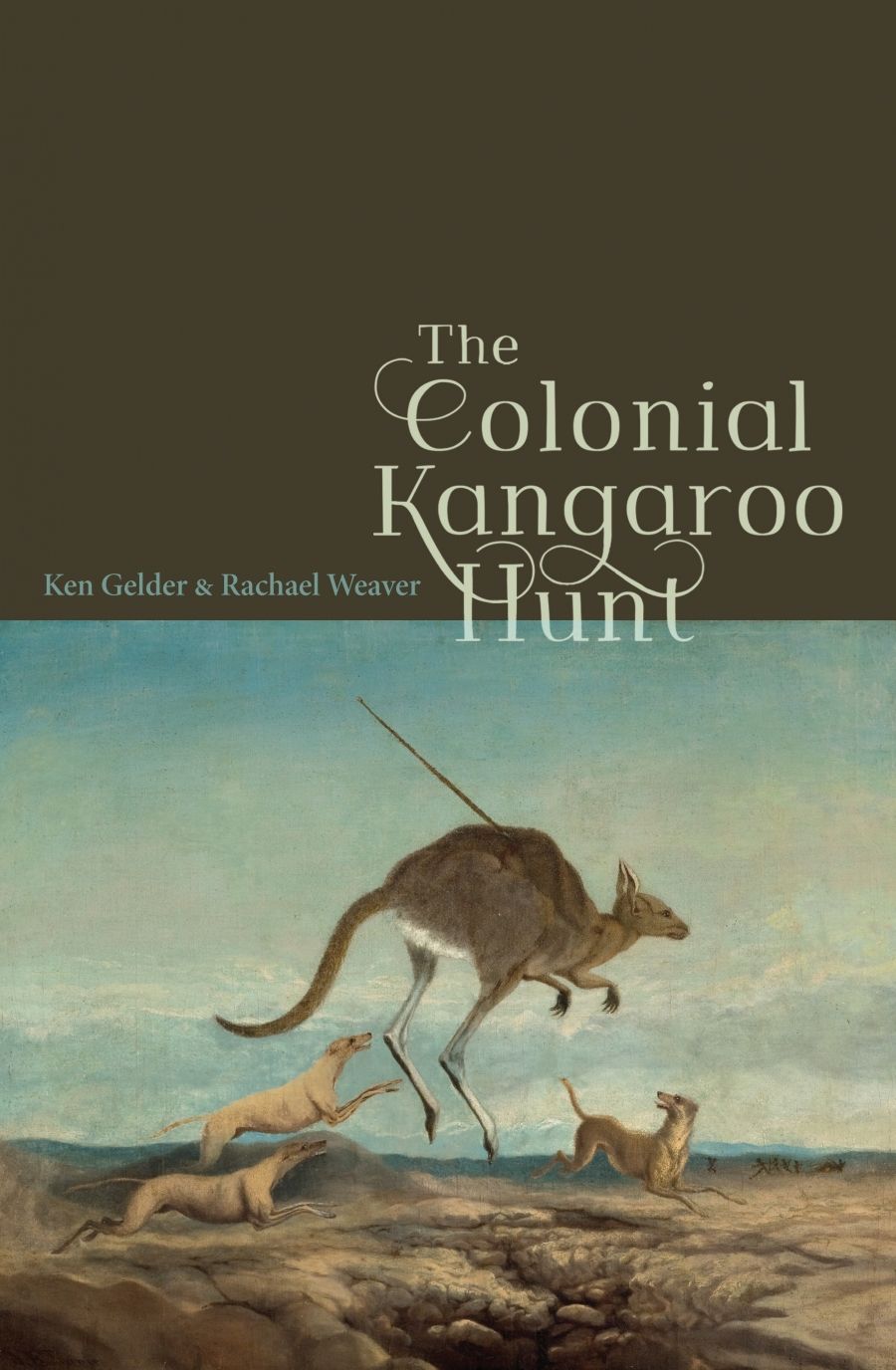

As generations of Australian tourists have found, the kangaroo is a far more recognisable symbol of nationality than our generic colonial flag. Both emblematic and problematic, this group of animals has long occupied a significant and ambiguous space in the Australian psyche. Small wonder, then, that Ken Gelder and Rachael Weaver have found such rich material through which to explore our colonial history in The Colonial Kangaroo Hunt.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: The Colonial Kangaroo Hunt

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $34.99 pb, 338 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/9XN3e

In the early years of colonisation, there was a huge enthusiasm for kangaroos in Europe, which even found their way to the Empress Josephine’s famed garden at Malmaison. And yet, in the colony itself, the focus on kangaroos was more as a source of meat. Matthew Flinders did not name Kangaroo Island for the beauty of its wildlife but rather ‘in gratitude for so seasonable a supply’ of fresh meat. There is nothing romantic about his pragmatic, although not unsympathetic, account of the slaughter. Kangaroo remained an important source of meat for sustaining the early colonies, leading to fatal conflict with, and displacement of, Indigenous communities.

In early descriptions of kangaroo hunting, it is often portrayed as a battle with formidable male kangaroos, as if, Gelder and Weaver contend, the kangaroo hunt was a metaphorical conquest of the country. Kangaroo hunts, often with Indigenous assistance, have been celebrated in poetry, prose, and paint, as beautifully illustrated by this Miegunyah Press title. Given that both the authors are literary scholars, it is not surprising that their primary focus is on the kangaroo hunt in literature – and an apt focus too, providing a rich and illuminating vein of research, and revealing much about the subtle shifts in the stories we have told about ourselves in the short time since European colonisation of Australia.

'A singular animal called Kangaroo found on the coast of New Holland', George Stubbs, 1724–1806 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

'A singular animal called Kangaroo found on the coast of New Holland', George Stubbs, 1724–1806 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

As invasion progressed into settlement, symbolic conquest soon transformed into a performative sport. Like fox and deer-hunting, kangaroo-hunting with dogs and horses enabled wealthier colonists to express their aristocratic aspirations. Visitors like Hyacinthe de Bougainville, Anthony Trollope, and Charles Darwin joined in, not always successfully. With hard soils and dense vegetation, the rough Australian terrain was not always as kind to ‘grand battue’ pursuits as the soft churned fields of Europe.

When Queen Victoria’s son Prince Alfred visited in 1867, he enjoyed ‘some first-rate sport’ on Yorke Peninsula with the hunting party shooting twenty-seven kangaroos. The rival colony of Victoria claimed to have more kangaroos on one run than all of South Australia, but the two Victorian hunts proved dismally unsuccessful. A small mob of roos was penned into a cattle yard where the regal visitor might take potshots at close range. What started as an attempt to ‘replicate familiar English landmarks, enthusiasms and hunting traditions’ and to import ‘an authentically aristocratic way of being’ rapidly degenerated into brutal slaughter.

The authors trace the ambivalent and shifting role of the kangaroo hunt through different literary traditions. Epic poems, similar to European odes to deer-hunting, glorified the ‘gallant’ hunt where the formidable male quarry of earlier accounts was more likely to be, disturbingly, a docile, often weeping, female.

Such Green Romanticism, however, is undercut by the work of Steele Rudd, whose biting parody ‘A Kangaroo Hunt from a Shingle Hut’ from On Our Selection (1899) satirises any attempts to ape the well-practised performance of English entitlement. A similar contrast is apparent in the depiction of Australian Kangaroo dogs which transition from idealised noble companions of ‘incomparable swiftness’ to Rudd’s half-starved ‘motley swarm’ with a keener taste for mutton than for wild meat, or Joseph Furphy’s notoriously disreputable ‘Pup’ in Such is Life.

The analysis of novels and children’s books reveals even more complexity around the nature and role of kangaroo hunting in Australian colonial society. Many of these works were by women, some of whom had never been to Australia but who had a strong connection with science and natural history. The ambivalent morality of the kangaroo hunt in these books is used as a test of character – through a coming of age, the raising or saving of children, or personal transformations. Perhaps even more importantly, these novels explore regret and remorse, not just over the treatment of native animals but more particularly about the European relationship with Indigenous people.

It would do this book a grave injustice to describe it as a historical account of kangaroo hunting. The moral trajectory of the kangaroo hunt is the story of colonial settlement and Indigenous dispossession itself. Like the literature it discusses, The Colonial Kangaroo Hunt provides a surreal and disconcerting, yet convincing, evocation of our colonial history. By focusing on our relationship with such singular animals, the authors cast into sharp relief our own ambitions and ambiguities, our cruelty and our empathies.

Comments powered by CComment