- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Towards the end of his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Overstory (2018), Richard Powers attempts to articulate why literature, or more precisely the novel, has struggled to encompass climate change: ‘To be human is to confuse a satisfying story with a meaningful one, and to mistake life for something huge with two legs. No: life is mobilized on a vastly larger scale, and the world is failing precisely because no novel can make the contest for the world seem as compelling as the struggles between a few lost people.’

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

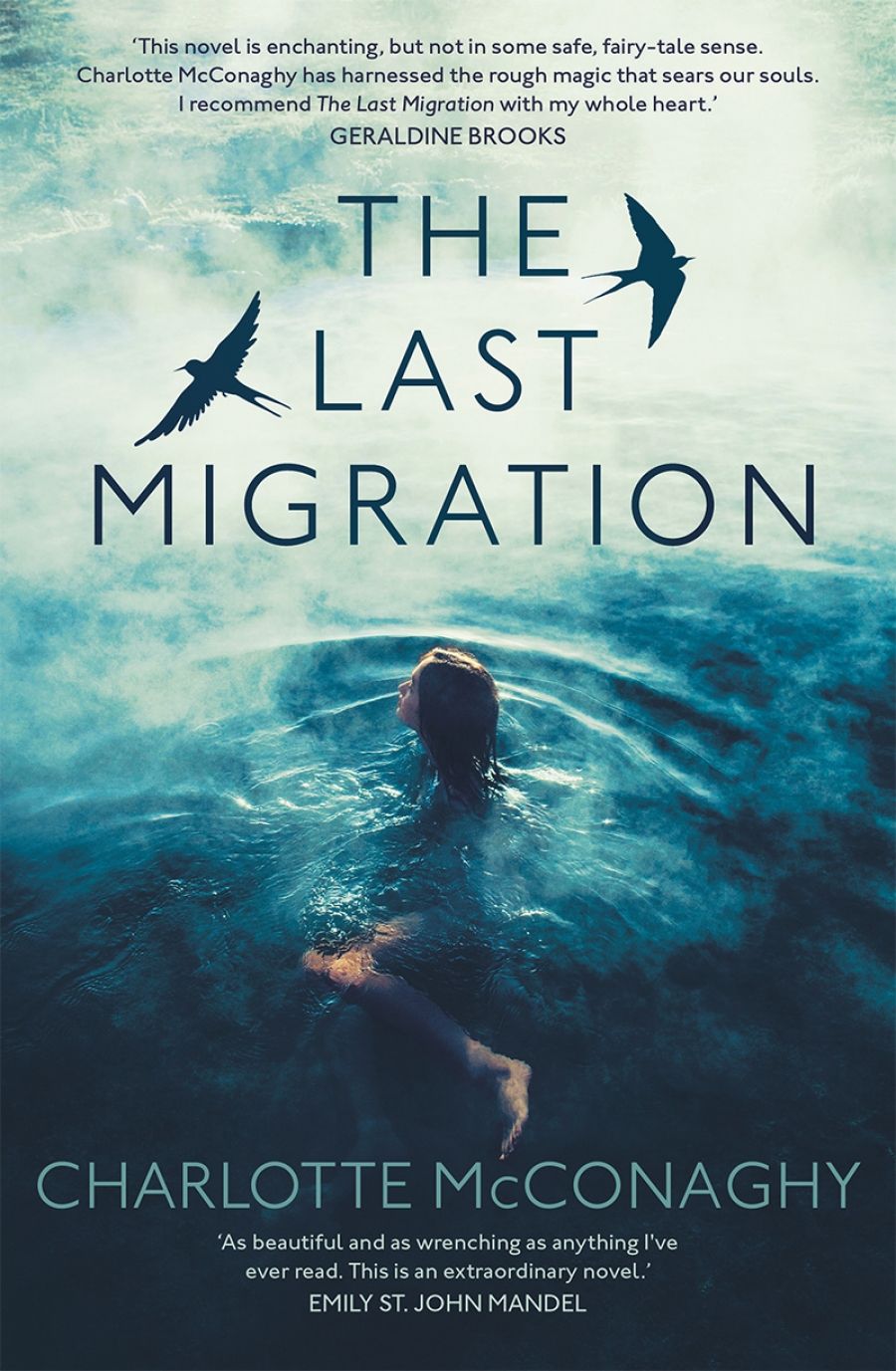

- Book 1 Title: The Last Migration

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $32.99 pb, 272 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/9XKjQ

The Last Migration takes place in what could be the near future, where ‘[t]here is hardly anything wild left’, ‘no bears in the once-frozen north, or reptiles in the too-hot south, and the last known wolf in the world died in captivity last winter’. The protagonist, Franny Stone, begins her journey in Greenland, where she plans to find a vessel that will sail south to track what will probably be the last migration of the Arctic tern to Antarctica, thus aiding her research into ‘what climate change has done to their flight habits’. Through a series of unlikely but highly entertaining interactions, Franny secures a berth aboard a fishing boat, the diverse crew of which is skippered by the enigmatic Ennis, a man with an Ahab complex, chasing the ‘Golden Catch’ in an ocean now devoid of sea life. Despite the inherent conflict between Franny’s conservationism and the crew’s labour, her contempt barely concealed, they set course, hanging on Franny’s word that the flight path of the terns will lead them to fisheries. This promise, along with the violent vagaries of the roaring Atlantic, make for tense sailing.

As the Saghani ventures south, the stakes increasing with every nautical mile, Franny’s extravagant backstory is revealed through interspersed flashbacks that depict her upbringing in Australia and Ireland, her meandering relationship with her ornithologist husband, Niall, and the tragic circumstances that led her to embark on this journey to the end of the world. As romance and drama, it is compelling and precisely paced to turn pages at a rate of knots; as environmental elegy, however, certain irreconcilable conflicts remain.

Chief among these is the overwhelming sense that the world centres on Franny: that these sailors would risk their lives for this dangerously unskilled passenger, bending their will to wherever the plot takes her, and that the terns will be waiting just for her at the end of her journey. This effect is partly due to the novel’s form. Written in the first-person present tense, it betrays a claustrophobic quality that, while serving the human drama well (particularly Franny’s harrowing relationship with Niall), nonetheless does little to further the sense that larger planetary stakes are unfolding.

Charlotte McConaghy (photograph by Emma Daniels/Penguin)

Charlotte McConaghy (photograph by Emma Daniels/Penguin)

For all the ways in which McConaghy excels at genre, there isn’t here any particularly strong impression of futurity, except through the persistent and well-articulated lens of biodiversity loss. The complex range of climate changes that would run parallel to – if not precede – such losses are consigned to the category of passing reference, as with there being ‘less snow than there once was. A warmer world.’ In an attempt at subtlety, some erasure of anthropogenic climate change occurs, and with it political urgency.

This stands in contrast to, for example, Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behaviour (2012), an exemplary climate-change novel that also focuses on migration and species loss and that interweaves the consequences of climate change with the quotidian circumstances of an unexceptional community, therein rendering the despoliation of the planet and the struggles of individuals not only equally compelling but also inextricably connected. Indeed, one’s capacity to become engrossed in The Last Migration might well depend on which side – need they be sides at all? – of these narrative scales the reader leans.

This would be to overlook one of the novel’s most important qualities: that while The Last Migration is certainly an exhilarating read – part romance, drama, psychological and legal thriller – it is one of few Australian novels to tinker with genre in such a way that allows for climate change to feature as a contextualising given, rather than as a central narrative device. This is surprisingly rare, disconcertingly so. For while there has been a sharp increase in Australian ‘cli-fi’ in recent years – novels that take climate change as their chief subject matter (Alexis Wright’s The Swan Book, or the recent novels of James Bradley and Alice Robinson) – there has been little by way of works that reflect our current climate reality, some kind of new realism. Amitav Ghosh, who has written both climate fiction and a monograph on art and climate change, put it well in a recent interview when he explained: ‘The reality is we are in a new world, in a new epoch … everything that we write about this world and of this epoch has to register this new reality.’ By this measure at least, McConaghy’s novel succeeds, even though it doesn’t manage to make ‘the contest for the world seem as compelling as the struggles between a few lost people’.

Comments powered by CComment